Age Science: Senses

thevisualmd.com

From the tip of the tongue to the inner ear, we go on a sensory journey.

SMELL

Like a super filter, our nose can recognize as many as 10,000 different scents. We also use that “nose” in tandem with our sense of taste for detecting flavour, but our sense of smell is also critical for detecting signs of danger and rotten foods. Thankfully, the rate of deterioration is quite slow with this sense.

“It stays stable to age 60, then it starts to decline,” says Craig Warren, PhD, the scientific affairs director for the Sense of Smell Institute. “We smell with a part of our brain called the olfactory system.

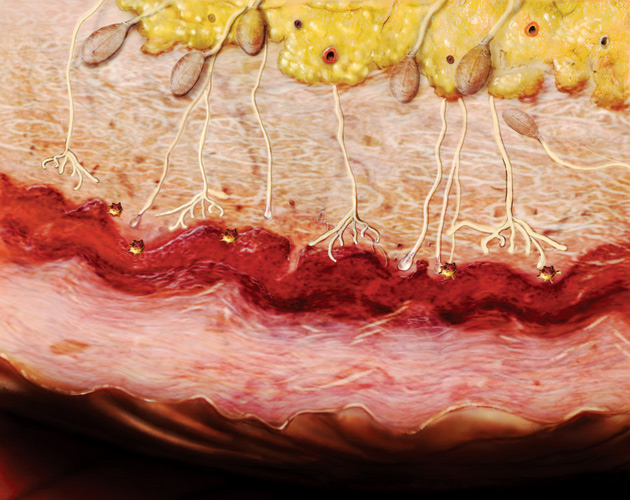

As we age, the tiny hair-like cilia that project from the olfactory receptor cells die off. As your threshold gets higher and higher, your sense of smell decreases,” explains Warren. “At age 80, there could be a general smell deficit. For example, the smell of vegetables disappears.” This is dangerous because it often leads to a decrease in appetite, as taste is also connected, and poor nutrition could follow.

What can you do? If you love perfume, Warren suggests, keep using it, but vary your fragrance type. Also, if you love food, make sure you keep up your sense of smell by sniffing ingredients (see “Taste”). “Olfactory neurons are only three synapses away from the emotions area of the brain called the limbic,” explains Warren. This is why the smell of apple pie baking in the oven sends you right back to helping grandma in the kitchen when you were young.

NEXT: SIGHT

SIGHT

As we age, optometrists check for glaucoma, cataracts and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is a disease linked to aging that affects your macula, a small area in the centre of the retina responsible for allowing the eye to see fine detail.

AMD slowly destroys precise central vision and, reports AMD Canada, is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly, affecting more than one-third of Canadians between 55 and 74 and nearly 40 per cent over the age of 75. According to Etobicoke, Ont.-based optometrist Yolanda Evans, as we age, we build up oxidative stress known as free radicals, which are destructive molecules we naturally produce. As our metabolic processes slow down, adds Evans, the macula becomes more vulnerable to stress. The tissue in that area is unable to neutralize the negative effects of the free radicals and, as a result, this leads to cell damage and loss of central vision.

What can you do? Evans recommends a yearly checkup after age 50. A study with older women funded by the National Institute of Health found that vitamin B may help protect against AMD.

NEXT: HEARING

HEARING

“Most age-related loss of hearing is called presbycusis,” says Ross Harwell, an audiologist from HEAR Toronto. “About 95 per cent of that loss has to do with issues in the inner ear.” Inside our inner ear is the snail-shaped cochlea and, inside that, are tiny hair-like structures called stereocilia, which turn vibration into an electrical signal that is sent to your brain; stereocilia deteriorate with age.

“Each hair cell has a mitochondria, which converts nutrients into energy,” says audiologist Evelyn Tassios of Markham Stouffville Hearing Services. “As presbycusis develops, there’s a partial reduction of oxygen leading to the formation of free radicals, which are highly toxic to cells and, as we age, the number of free radicals in our cells increases.”

What can you do? Once you reach 50, it’s a good idea to have a hearing test, advises Tassios. Harwell says that 50 per cent of people over 65 could benefit from a hearing aid, which acts as an amplifier, microphone and speaker. “Aids are programmed to fit specific types of hearing loss, are digital and can be customized by your audiologist.”

NEXT: TOUCH

TOUCH

As the years pass, our sense of touch becomes less acute because the skin’s sensitivity decreases. According to a report from North Dakota University, the skin becomes less elastic and tissue loss becomes apparent. Our sensitivity decreases, it is believed, due to a decreased number of nerve endings available to send interpretive signals to the brain and changes in the amount of fat below the skin.

“The function of your neurotransmitters diminishes, and that’s where you lose your sense of touch,” says physiotherapist Helen Ries from Royal Centre Physiotherapy in Vancouver. People with decreased sensitivity may have problems with their fine motor skills.

What can you do? Ries works to stimulate her patients’ touch receptors. “They touch different surfaces — fine, hard, smooth, hot and cold — to maintain the sensitivity to their sense of touch.”

NEXT: TASTE

TASTE

Taste, along with smell, is usually the last of the senses to go. North Dakota University reports that at age 30, a person has 245 tastebuds on each tiny elevation, called a papilla, on the tongue. By age 70, the number of tastebuds decreases to about 88.

“The actual size of tastebuds [also] decreases,” explains Eve DeRosa, PhD and assistant professor in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. Luckily, what we know as flavour doesn’t all have to do with tastebuds. Taste comes 25 per cent from your palate, 75 per cent from smell. Since there’s such a big link with your olfactory system, smells are memorized by the brain and programmed into your mind.

What can you do? Keep scents sharp in your mind and exercise this sense as it relates to taste. Experiment with different and new ingredients when cooking.