Aging And The Perception of Time

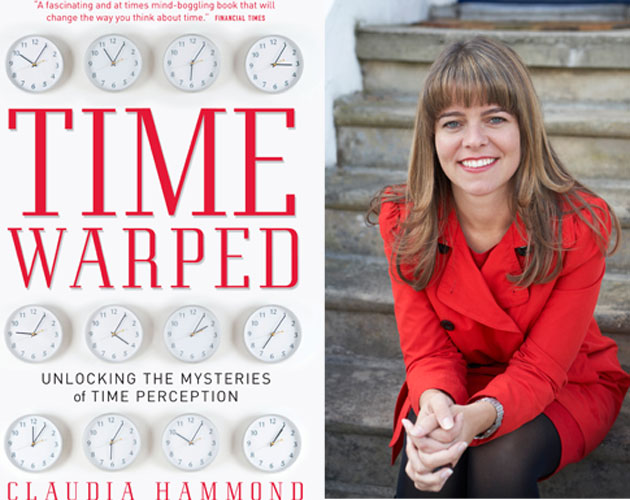

Ever feel like time is running away from you? Or wonder why time spent waiting at the doctor feels like an eternity, while dinner with friends flies by? Claudia Hammond’s recent book, Time Warped, explores the passage of time, as well as its connection to age, space and emotion and memory. In this exclusive essay for Zoomer, she ponders the concept of future thinking and its affect on our memories.

Remembering The Future

By: Claudia Hammond

When the British film director Danny Boyle was thinking up ideas for the opening ceremony at the Olympic Games in London, as well as creating something extraordinarily original, he was using a skill we all have – future thinking. He was able to throw himself mentally forwards into the future, imagining what it would be like to be at the opening ceremony – how those industrial towers rising out of the ground would look, how it would feel to hear the beating of the drums and to watch those individual flames slowing rising on poles to form a giant cauldron. When imagining a future event you can pre-experience it as though through a window in the mind. This allows you to guess what will work and what won’t. The consensus is that Boyle’s imaginings did work and although his level of creativity might not be something we can all achieve, we can all mentally time travel into the future in an instant. At will we can plunge ourselves back into our memories of the past or we can consider the endless possibilities provided by the future.

This is a skill which helps all of us at work and in our home lives. If we are working out how to have a tricky conversation with the boss or planning a family Christmas we use the skill of future thinking to picture what an event might be like.

Future thinking is critical to our success, allowing us to make plans and to try out different possibilities in our minds before we commit. When people are put into a brain scanner and asked to think about nothing, it is the future that beckons their blank minds, activating the areas associated with contemplating the future. It is as though speculating about the future is the brain’s default when it has nothing else to do. And it is easy to see why.

The cognitive neuroscientist, Moshe Bar, from Harvard Medical School goes a step further. He believes that daydreaming about the future and even about negative events such as disasters which might befall us, creates memories to which we can turn for help if something does go wrong.

But future thinking comes at a price – the fallibility of our memories. It can explain why witnesses to crimes can find it hard to remember as much detail as they’d like and why it’s far easier than you might expect to get people absolutely convinced that they have had experiences which never happened. The psychologist Elisabeth Loftus persuaded people they had once met Bugs Bunny in Disneyland. As a Warner Brothers character there is no way he would have been there, but the people who took part sincerely believed that they could remember meeting him.

Far more research has been done on memory than on thinking about the future, but the two are more closely related than you might imagine. If you ask three year olds what they might do the following day, only a third of them can give a plausible answer. Memory takes time to develop and so does the skill of imagining the future. When the psychologist Cristina Atance gave small children some pretzels followed by the option of more pretzels or some water, the children, feeling thirsty after eating the salt, chose water. But when she asked them what they would like to have the next day most still opted for water, while adults go for pretzels. The young children were unable to escape from the present and to pitch themselves mentally forward into a future where they would feel hungry instead of thirsty.

In 1981 a man was driving up the exit slip-road from a motorway when he came off his motorbike, sustaining a head injury so serious that he developed amnesia. But as well as losing the ability to form new memories, he became unable to imagine the future. When asked the question “What are you plans for the summer?”, he said his mind was blank. Anyone who finds it difficult to remember their own past, which can include people with Alzheimer’s Disease, depression or schizophrenia, also find it harder to project themselves into the future.

The nature of memory is such that we alter memories as we lay them down, filling in gaps to make sense of them. Then we change them if we get new information about an event and we reconstruct these memories each time we think or talk about them. It’s a flexible process which is why it’s easy to tamper with. Memory is not like a video archive of everything that has ever happened to us. If it was, then for Danny Boyle to picture his opening ceremony he would have to search his mental archive to retrieve tapes of a vast range of images and past memories – from watching Shakespeare to walking through the countryside or laughing at Mr. Bean. If memories were like videotapes this would take time. Instead memory is so flexible that we effortlessly remix different elements, instantly allowing us to preview the future.

There’s just one problem with future thinking which is that your thoughts might be negative and you might find yourself constantly pondering them – in other words, worrying. Evidence suggests that excessive rumination can contribute to depression, but there are some tested techniques for worrying less. The Dutch psychologist Ad Kerkhof advises setting aside a daily time just for worrying. You sit down for ten minutes and do nothing but worry about whatever is bothering you. When those thoughts intrude at other times of day, you banish them from your mind, because you had a time for worrying later. In his trials this reduces the time that spend dwelling on a negative future.

The Planning Fallacy

In 1857 the idea for the Oxford English Dictionary was born and it was predicted that to collate and define every word in the English language would take about two years. Five years later they had only reached the word “ant”. The final dictionary was delivered more than seventy years late, by which time it was out of date and had to be revised. This is a classic example of the planning fallacy – the belief that we can do things in a shorter time than is possible. Whether it’s painting a room or finishing a report for work, we’ve all done it. Psychological research reveals that most of us have an unjustified optimism that in the future we will not only have more time to spare, but that we will be better organised versions of ourselves. Sadly these are both unlikely. But there is a solution. We are much better at estimating how long it will take other people to do things. So next time you’re wondering how much time to leave yourself to get something done, ask someone else.

Claudia Hammond is an award-winning broadcaster, writer and psychology lecturer. She is the presenter of All in the Mind & Mind Changers on BBC Radio 4 and the weekly Health Check on BBC World Service Radio, as well as being a columnist for bbc.com. Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception was published by House of Anansi Press in Canada.