D-Day: 78 Years After His Father Endured a Nazi Attack, a Canadian Man Travelled to France to Retrieve Remnants of His Harrowing Survival

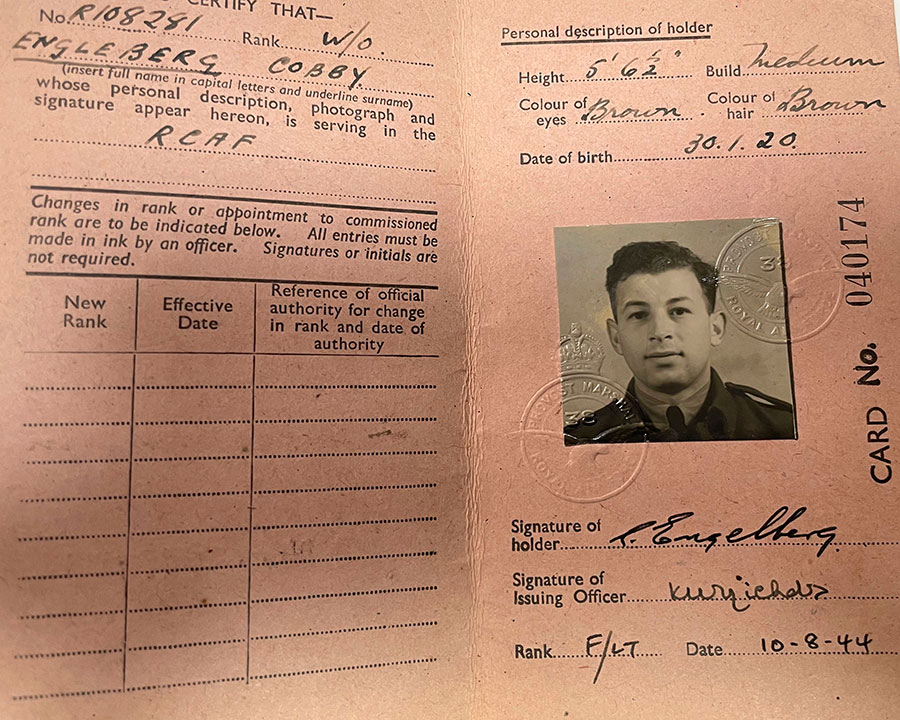

Cobby Engelberg training in Canada as a wireless radio/air gunner (WAG) in 1943 at approximately age 23. A year later he survived a Nazi attack and plane crash during the D-Day invasions — the story of which his son has been tracing for decades. Photo: Courtesy of Harvey Engelberg

The mere mention of “June 6” triggers images of Allied troops storming the iconic beaches of Normandy during D-Day, the greatest invasion gamble of the Second World War. And with all those years of research, analysis and interviewing of the battle’s veterans since 1944, it seems impossible that any stories remain unfound or untold. Freelance contributor and military historian Ted Barris contends there will always be new D-Day stories unearthed — such as this one, in which a son is gifted physical remnants of his father’s harrowing survival following a Nazi attack.

One day in April, almost 78 years to the anniversary of D-Day, at a farm kitchen table in Basseneville, France, Harvey Engelberg came face-to-face with his father’s June 6, 1944, war story. There, on a red-and-white plaid tablecloth, Thérèse Férey and her husband Ghyslaine opened a towel to reveal 42 pieces of wartime-era aluminum. The Féreys had recently salvaged the Second World War artifacts from a forgotten corner of their farm. The jagged bits were all that remained of a DC-3 transport aircraft that had carried RCAF wireless radio operator Cobby Engelberg and a plane-full of paratroops into the middle of the greatest amphibious invasion in military history — Operation Overlord.

“Here,” Madame Férey said to Engelberg, now 69, at that first-ever meeting of the two. “We found these, but they belong to you.”

Harvey Engelberg knew very well the bits were aluminum, since much of his adult life in Montreal he has manufactured and sold the non-corroding metal as utensils to customers in the restaurant business. But their connection to the mystery of his father Cobby Engelberg’s D-Day experience shook him right to his core.

“My father never talked about the war,” he said during a recent interview, “but questions about his survival on D-Day have lingered since the time I was 18 or 19.”

Cobby Engelberg died in 1978. Several times during his adult life, Harvey had tripped over clues to his father’s tale — a scrapbook of clippings his mother had saved, post-war correspondence with a family named Duhamel on a farm near Basseneville, France, and official Royal Canadian Air Force records. The RCAF missives reassured the Engelberg family back in Canada in 1944 that, while missing-in-action, there was every hope that 24-year-old Warrant Officer Engelberg may well have survived when his Dakota transport plane was shot down in the pre-dawn hours over Normandy on June 6. But each time son Harvey tried to trace his father’s D-Day story, he came up empty. Eventually, he decided to write to the Féreys.

“Then, on March 7 this year I got a letter from the Féreys, the current owners of the farm, about their discovery,” Engelberg said. With a business trip to Israel already booked, he added a side trip to that farmhouse kitchen in Normandy. Suddenly, the vastness of the D-Day invasion, his father’s role in it, and the tale of WO Cobby Engelberg’s miraculous survival all began to fall into place.

The Story of Cobby Engelberg’s D-Day Survival

Hours before an armada of landing craft debarked 175,000 Canadian, American and British infantry troops in a surprise attack on the five invasion beaches on D-Day morning, WO Engelberg’s Dakota KG356 transport was flying over Normandy with 22 paratroops aboard. In the darkness, his pilot, RCAF Flying Officer Harvey Edgar Jones, had orders to release the paratroops over a drop zone protecting the flanks of the invasion beaches — Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword. In mid-operation, however, German anti-aircraft flak struck the plane. Pilot Jones ordered the stick (unit) of paratroops and three other members of his Dakota aircrew to jump from the doomed transport. Jones himself chose not to parachute to safety; his wireless radio operator/air gunner (WAG) Engelberg lay unconscious from flak explosions aboard the plane, so Jones attempted to crash-land the Dakota to save himself and Engelberg. That was all son Harvey knew about Jones’ sacrifice. Jones died on impact.

“Harvey Edgar Jones gave life to my father, who gave life to me,” said Harvey Engelberg, named in remembrance of his father’s saviour that night.

From post-war correspondence between his father and the Duhamel family, Harvey Engelberg learned that civilians in Basseneville found his father under the wing of the burning Dakota that night. They dragged him — still unconscious — to a nearby farm where Madame Duhamel attended to Cobby Engelberg’s fractured skull and burns for five days. The WAG did not awake for 10 days.

In that time, he’d been transported back to England, where he spent another six months in rehabilitation before his repatriation to Canada in early 1945. Meanwhile, the Duhamels also hid and buried the body of pilot Harvey Jones (later re-interred at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Ranville, France).

78 Years Later …

Stories and tears flowed freely at that Normandy farmhouse kitchen table in April before the family led Harvey to the field where they’d found the Dakota fragments. His voice breaking with emotion, Engelberg said a Kaddish prayer for the dead in Hebrew.

“Sharing this common bond, 6,000 miles apart, 78 years later, a French Catholic family and a Jewish boy from Canada,” Engelberg said, “all of a sudden we were united in this group hug. It was like something out a Disney script.”

Engelberg ultimately donated the aluminum fragments of his father’s downed aircraft found on the farm to the museum at Normandy’s Juno Beach Centre.

And yet the emotional jolts and D-Day discoveries have continued since that impromptu Basseneville gathering. Further research and contacts with official and social media sources have shed more light on Cobby Engelberg’s escape from Nazi-occupied Europe and the price paid by French civilians for hiding him. Harvey has since learned that the Germans eventually arrested members of the Duhamel family for hiding Jones’ body and nursing Engelberg in secret; in retaliation the Germans executed the Duhamel’s 16-year-old son.

As if the six degrees of separation had not connected him with sufficient witnesses to his father’s D-Day story, Harvey Engelberg has since met Michael Pine-Coffin online. His grandfather served with the British 7th Light Infantry whose two medics happened to parachute into the same Normandy district where Dakota KG356 came down on June 6. Ernie Mold and George Jamieson were both conscientious objectors serving with the 225 Field Ambulance.

“They had so many casualties on D-Day,” Pine-Coffin told Harvey Engelberg. “(But) Jamieson treated your dad,” then likely had to move on, leaving Cobby Engelberg in the care of the Duhamels. The two British medics must then have learned of Harvey Edgar Jones’ sacrifice to save his comrades in the Dakota transport.

“Harvey Jones … was recommended for a VC (Victoria Cross),” Pine-Coffin wrote, but so many pilots were lost in those first days of the invasion, that not all could be awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest medal of valour. So, while the military may have passed by Harvey Edgar Jones’ sacrifice on D-Day, Cobby Engelberg’s son could not. Not a day goes by that Harvey Engelberg doesn’t consider the gift such wartime sacrifice bestowed him.

He admits, “It’s a heavy debt (Jones’) name carries.”

Ted Barris is the author of 19 bestselling non-fiction books of history. His 20th book — Battle of the Atlantic: Gauntlet to Victory — was published by HarperCollins in September 2022.

A version of this story was published on June 6, 2022

RELATED:

I Was There: Canadian D-Day Veterans Recount the Triumph and Terror on Juno Beach

D-Day 75th Anniversary: Juno — A Beach to Remember

D-Day Remembered: A Photo Tribute to the Canadian Boys Who Landed on Juno Beach