Second Act Success Stories: Back to School … And Not Just for Kids!

Photo: Elkhamlichi Jaouad/EyeEm/Getty Images

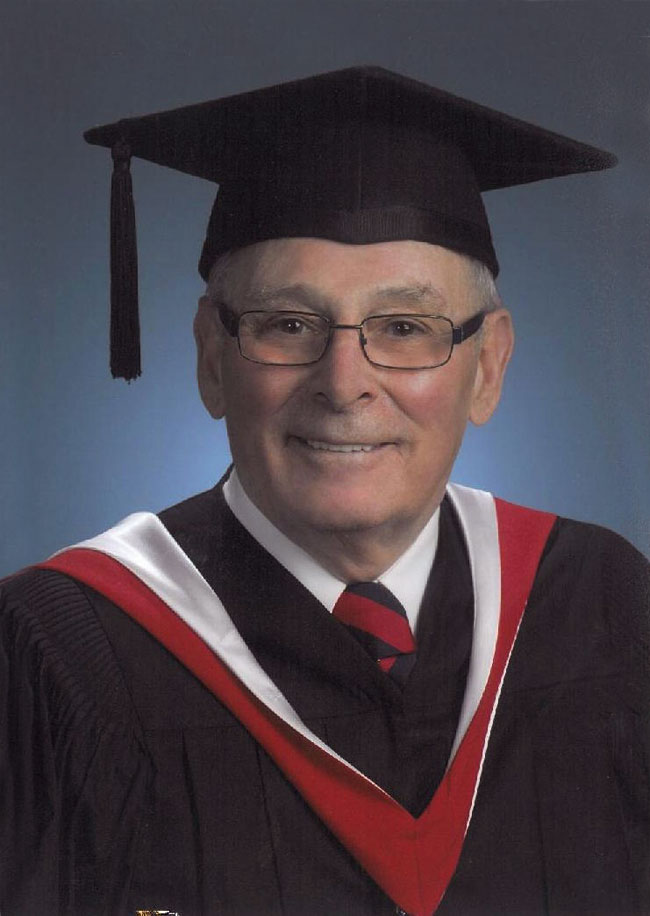

Donald Baker used to own and operate small businesses. Then he went on to play Santa Claus on the big screen.

At 74, the Toronto entrepreneur wrapped a Canadian feature film with a Christmas theme, and he also directed two 10-minute plays for theatre festivals.

While Baker acted in high school and university productions, he didn’t take his first lesson — at Ryerson University’s Estelle Craig Act II Studio — until he was 66. At his side was his partner, Cathy Shilton, who, as a teen, wanted to run away to Hollywood to be a star. Her father sent her to boarding school instead.

Now Shilton is an actor-playwright while Baker is an actor-director with several credits on his resume, including a turn as notorious music mogul Phil Spector in a Hollywood Homicide Uncovered episode.

Though it’s not a new career, he does call it his “second act.” And wrapped up in that is one of the prime motivations common to older adult education.

“Along with the fun, it’s a real challenge, it’s a new experience and it keeps me young,” he says.

At the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, professor Bill Kops has been studying older adult education for more than 10 years. His previous research has shown older students take non-credit courses for the sake of learning, for social reasons and to keep the brain sharp. Kops says the health benefits of learning are legion. “Active bodies and active minds lead to healthy people, whether they’re young or old.”

But his 2016 research into how and why universities participate in older adult education is eye-opening. Just 18 of 50 English universities surveyed by Kops, all members of the Canadian Association of University Continuing Education, had any older adult programming.

Courses are typically offered through continuing education departments, where costs are almost always covered by tuition because there is no government funding for students in non-credit courses. The fees are low so seniors can afford them, but these courses are often the first to be cut when budgets tighten because they bring in less money.

“Continuing education units have changed organizationally,” Kops says. “They are not as big or bold or robust as they used to be, so programs for older adults will not necessarily find a home that easily within the university, and they may be relegated to the further peripheries of the university, or not exist at all at the university.”

It’s not that schools don’t recognize the value of serving the growing cohort of aging boomers, but they are dealing with increased costs in an age of government cutbacks. That’s part of the reason extended education at the University of Manitoba, where Kops teaches courses on adult learning and continuing education administration, currently has no programming for older adults. But demand will only grow as experts predict there could be 9.9 million or more Canadians aged 65 and older by 2036, or almost 25 per cent of the population.

Add to that the concept of “active retirement,” where seniors don’t want to slow down and hit the recliner in front of the TV, and we have a grey tsunami on the horizon.

“We’re living so much longer, and there’s more to life than playing golf, watching your grandkids or whatever,” says Roz Kaplan, director of liberal arts and the 55-plus program at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C., one of two schools Kops singled out for praise. “One of the three pillars of SFU is an engaged community,” Kaplan explains. The university, which has worked with non-traditional learners since 1974, has about 3,000 older adult learners with an average age around 70.

Ryerson University in Toronto, the other school Kops singled out, made a serious commitment to lifelong learning 20 years ago. That’s when it hired Sandra Kerr, now director of programs for 50-plus at the Chang School of Continuing Education, who oversees courses for 3,000 non-traditional learners.

She says one of the challenges with older adult learners is that they never graduate.

“They don’t come for three years and then … go on to something else, so we’re always developing something new.”

Where there are gaps in older adult education, learners are taking on the work of planning lectures and classes through organizations like the Seniors’ College Association of Nova Scotia and the Third Age Network, founded in France in 1973, which has about 100 member groups across Canada.

Third Age Barrie, an hour’s drive north of Toronto, regularly sells out five-part spring lecture series on topics like Misunderstanding Africa and, this year, City Futures: Facing Big Issues in the Age of Immediacy. Kerr says the Ontario network has added organizations in Guelph, Owen Sound, Collingwood and Windsor, to name a few. “They’ve just really grown like gangbusters in the last year or so.”

He’ll Always Have Paris

Like so many before him, Brian Aspinall fell in love with Paris. It was the breathtaking beauty of the Sorbonne university’s grand art-lined lecture halls that captivated the 15-year-old on a French course from his high school in Manchester, England.

“Even then it had a real cachet,” says the retired IBM Canada sales executive from his home in King City, Ont., 35 kilometres north of Toronto. “All I can remember of the three weeks in Paris is the Sorbonne. I can’t remember where we stayed or what we did.”

It stuck with him through his business studies at the University of Birmingham and his sales career with IBM, which brought him to Canada in 1975.

But it wasn’t until 2002, when Aspinall was 63 and mostly retired, that he enrolled at Alliance Française before a visit with his Paris-based brother.

There he found a community of like-minded retirees with rich life experiences, and that’s where he heard about a bilingual liberal arts college at York University in Toronto. When, at 70, he enrolled in the French studies program at Glendon College, his proficiency was “high-intermediate or low-advanced.”

Learning French was never about exercising his brain or even about socializing, since his classmates were mostly females in their late teens and early 20s. The goal was always to learn more about French and Québécois culture and improve his comprehension and vocabulary.

Although his classmates could whip off a paper the night before, he had to chip away at it for days. Failure was not an option, and his commitment to succeed was his major motivation.

“The pressure was entirely internal because I wanted to do well,” he says. “I didn’t have to get the best marks but I certainly didn’t want to fail.”

Aspinall was 77 — and York’s oldest graduate of 2016 — when he walked across the convocation stage to collect his Bachelor of Arts with a B-plus average.

He still takes classes at Alliance Française with the same people he started studying with 15 years ago. Now good friends, they meet outside class – and take trips to France — to practise their French.

Aspinall was in a class by himself when it comes to older adult learners who take courses for credit. In 2015, Statistics Canada data shows 400 out of more than a million full-time post-secondary students were over 65, while 2,300 of almost 300,000 were studying part-time, a trend that hasn’t changed much for the silver set in the past five years.

Aspinall has been back to the Sorbonne, sat in its historical halls and imagined himself listening to a lecture on 17th-century French playwright Jean Racine.

Not only could he comprehend it but, at 78, he could ask an intelligent question, understand the answer and retire to a café to debate the nuances of the text. Not content to stop there, Aspinall wants to do it all over again – this time in Spanish.

I’m with the Band

Irv Griffith grew up in Little Burgundy, a Montreal neighbourhood he says is famous for two things: jazz pianists Oscar Peterson and Oliver Jones.

Although Griffith, 69, was taught to play piano by Daisy Sweeney, Peterson’s older sister, he quit after a year.

“My mother said, ‘You’ll be sorry one day,’ and, as most mothers are, she was always right,” says Griffith, a retired IT specialist at McGill University.

Although his parents were not musical, his life did not lack a soundtrack. A friend’s father introduced him to American blues singer and pianist Champion Jack Dupree, while his older brother was a jazz drummer who played the Montreal clubs.

In his late 40s, Griffith signed up for private piano lessons, sticking with it until he got a CEGEP diploma in music, even as he worked full-time. Then he picked up the saxophone. That’s when he heard about the Montreal New Horizons band, formed in 2014 as part of Audrey-Kristel Barbeau’s PhD research at McGill into the biological, psychological and social benefits of learning to play an instrument after 60.

When Barbeau, now a professor of music education at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), defended her thesis, band members were in the audience. “One of the reviewers said she changed the way McGill operates in the music education area,” Griffith recalls. “I can’t say enough about her.”

The Montreal band is part of the New Horizons International Music Association, started by a U.S. music professor to create music-making opportunities for adults. Now, there are close to 200 chapters, with almost 20 in Canada. The bands charge a fee to join, which can vary; in Montreal, players pay $120 for a 12-week term, with three terms a year. There is no set graduation date, and many players stay for years, while some move on to community bands.

Barbeau now has a beginner and intermediate band, but the prof invites members like Griffith to play with university students, who are learning new instruments, and music-education students to conduct and play with the New Horizons bands. It is an intergenerational experiment, mixing boomers, gen-Xers and millennials. “There’s even an eight- or nine-year-old boy who comes and plays with his father,” says Griffith. “It’s a really wonderful environment.”

Band members report improvements in muscle control and breathing; some say playing maintains strength and flexibility in arthritic hands. Then, there are the social and psychological benefits. “One woman realized that a younger person lived on the same street, and they started going to movies and practising together, and they are 35 years apart in age,” says Barbeau.

Next she wants to measure stress hormones and immune-system response in band members to see if and how music soothes the soul.

Griffith’s short-term goal is to master a song called “Slow Walk” exactly the way American jazz saxophonist Sil Austin played it. Then he’s thinking about adding another instrument to his repertoire. “I really like the sound of the bass clarinet,” he says. “Oh what a rich, beautiful sound.”

Send in the Clowns

When Toronto resident Elaine Lithwick saw a newspaper story about Caring Clowns, a continuing education course for older adults at Ryerson University, she had just retired from a 39-year career as a social worker in family and children’s services.

“Laughter is the best medicine,” it read. “Bring laughter and joy to dementia residents in long-term care facilities.”

Lithwick, then 62, tucked it away because she was heading to Ottawa to help care for her mom, who was living with dementia in a long-term care facility.

“I hadn’t really thought about what my next step would be,” she recalls. “I was retired for two months. Other than meeting friends for lunch and going to the gym, I thought, ‘What else is there to do?’”

After her mother died in 2013, Lithwick wanted something “light and bright and happy, where it would make me happy as well as make other people happy.”

The first class, learning to act silly, was terrifying. Lithwick kept her eyes glued to the ground, hoping instructor Lynda Del Grande would not call on her.

“It’s hard when you’re 60-plus and you’re coming from a serious job,” Lithwick says. “You like silly, but it’s not a part of you.”

Students get their clown noses in the first introductory course, which begins in the fall. By January, they are developing their character and putting together costumes. The practicum starts in March and in June and after 50 hours of training and about $600 in tuition (bursaries are available), they graduate.

Lithwick, who has a sunny disposition, decided on Sunbeam as her clown name. She wears a bright yellow shirt, pink pedal pushers under a multi-coloured skirt, odd socks and running shoes with soles that light up. Her clowning partners include Dim Sum, Senorita Rosita, Feathers, Poppyseed Joy, Yupi, Tatee and Lorna Dune Singing a Tune, who plays a ukulele.

“We’re not scary clowns with white face, nor do we have seltzer bottles and flowers that squirt water,” Lithwick says, explaining they act more like a zany relative. They play music — “a lot of people love Elvis,” she says — and sing and even have dance parties.

“When we’re there, they put a smile in our heart and we put a smile on their face. Whether they remember we were there, it doesn’t really matter because while we’re there, they’re in the moment and we’re in the moment.”

About 50 people between 55 and 90 have completed the program since it began in 2009, while about 15 are currently active. Lithwick, who volunteers three mornings a month, says her clown colleagues are good friends. They often carpool to their gigs and grab a bite after. “It really is a camaraderie,” she says. “We go out to lunch together, we laugh. It feels good.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the July 2018 issue of Zoomer magazine.