Many of the classic schoolyard games we loved growing up have quite the history beyond the scraped knees and other madcap mishaps. Here, some recess faves and their fascinating origins.

Today’s kids are obsessed with tech — just try and get someone under 12 to go outside and play catch. Try it, we dare you. Or if they do look up from their devices it’s to play Pokemon or twirl a fidget spinner. Back when we were ahem, young, nothing beat getting to outsmart and outrun your best buddies (and the occasional schoolyard bully, too).

These iconic games have been passed down generation to generation and we know why — they’re timeless fun!

1. Simon Says

Simon Montfort, the 6th Earl of Leicester is rumoured to be the man Simon Says is named after — but, if true, he wasn’t exactly the embodiment of family fun you’d expect him to be. Actually, he wasn’t much of a family man at all. In 1264, he led a revolt against King Henry III of England — who also happened to be his brother-in-law.

After defeating the King’s forces in the Battle of Lewes where he was outnumbered two to one, he captured the King and seized nearly all of his power.

For the next year or so, Henry maintained the title of King while Montfort pulled the strings from behind the scenes. This is where the rules of Simon Says likely originate: The player who is designated Simon gives the other players instructions like touch your toes or jump up and down, which are only to be followed if they are preceded by “Simon Says.” If another player either performs a standalone instruction or doesn’t perform when required to, that player is eliminated from the game.

The game of Simon Says that King Henry played with Montfort wasn’t as fun, though. Under his control, the King was forced to participate in two parliaments where, for the first time, representatives from the counties and boroughs were invited to discuss the business of the realm beyond taxation.

Considering this was the first steps toward representative democracy in England, it was likely as difficult as simultaneously rubbing your tummy and patting your head for the poor royal.

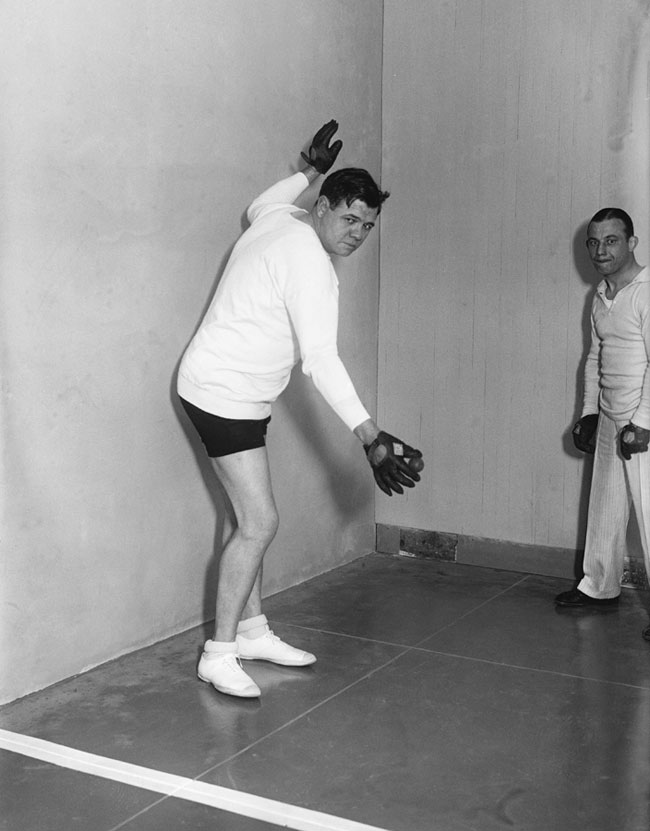

2. Handball

Handball has a long genealogy. Depictions of people playing some form of the sport were discovered on the tombs of ancient Egyptian priests and in sculptures and pottery from around 1500 BCE found on pre-Columbian sites in South America.

The version of the game most of us grew up playing involved a tennis ball, a flat wall and a concrete court with sidelines and end lines. The object of the game was to throw the ball so that it bounced once on the ground before hitting the wall. Players lost a rally when they were unable to return a ball legally or keep their return in play.

A testament to the addictiveness of this simplistic yet competitive game was demonstrated throughout the 1600s in Europe, where it was common to see notices prohibiting handball play against church walls.

In 1527, ball play against the town walls in Galway, Ireland was banned entirely.

But perhaps the most irrefutable evidence of its irresistible charm was the hefty price that King James I of Scotland paid for his obsession with the sport nearly 100 years earlier.

After losing several of his balls to a nearby sewer that ran underneath his handball court, he handled the inconvenience like any king would and ordered his men to fix it.

A few days later, the King attempted to escape assassins through that same tunnel and met an unfortunate end.

Centuries later British poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti described the assassination in The King’s Tragedy:

“Alas! In that vault a gap once was wherethro’ the King might have fled: But three days since close-walled had it been by his will; for the ball would roll therein when without at the palm he play’d.”

In other words, the King’s love of handball sealed his fate (pun intended).

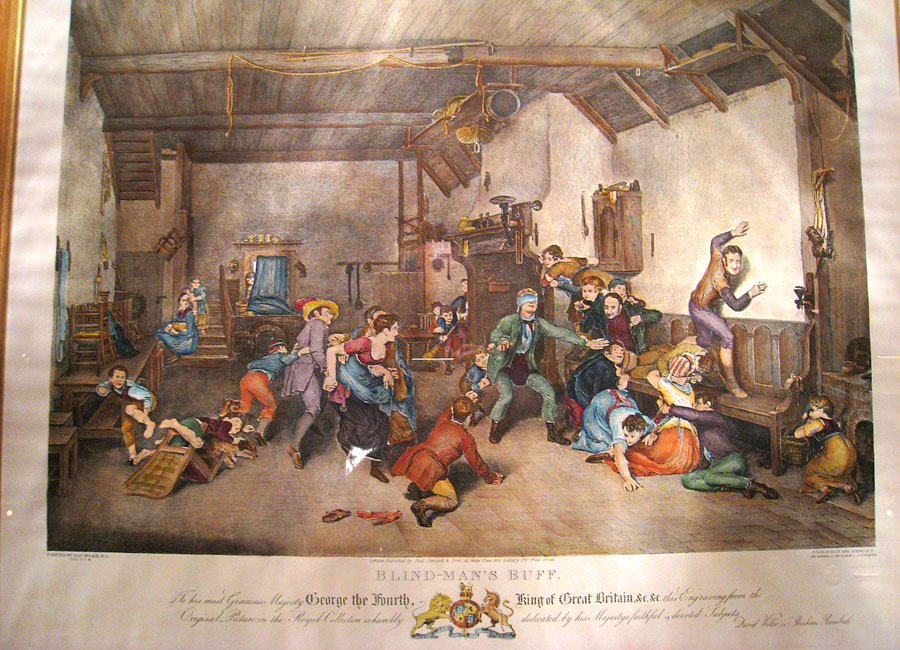

3. Blind Man’s Buff

It was originally called Blind Man’s Buff but most of us know this variant of tag as Blind Man’s Bluff.

The change in name may have been a classic case of broken telephone, occurring over the game’s 2,000 year history dating back to ancient Greece.

But it may have also had something to do with the omission of a particularly violent aspect of the game that existed in earlier versions.

In the Blind Man’s Bluff we played growing up, the blindfolded player who was “it” was often teased verbally by the other players as they evaded capture. This was tame compared to the variant played in the Middle Ages, where participants would harass and buffet (repeatedly strike) the “blind man.”

Among the Igbo in Nigeria, a variation of the game is called Kola onye tara gi okpo? Which roughly translates to “can you find the person who knocked you on the head?” In this variation, children form a circle around the child who is “it.” Instead of taking the risk with a potentially faulty blindfold, another player covers the eyes of the unlucky player in the centre. A player in the surrounding circle then smacks the “blinded” player in the back of the head and returns to his or her position in the circle. If the “blinded” player identifies the assailant once his or her eyes are uncovered, the offending player must assume the position in the middle.

Later, the game was also popular among adults. The English diarist Samuel Pepy reported a game played by his wife and friends in 1664, while English poet Laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson, is said to have participated in a game in 1855.

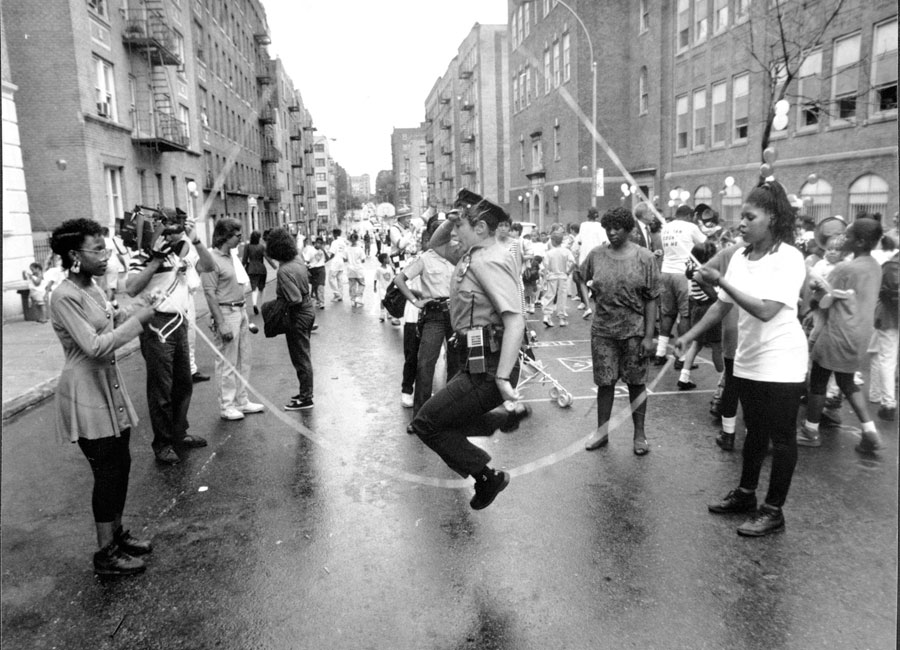

4. Double Dutch

Not surprising to the less coordinated kids in the schoolyard, Double Dutch jumprope may have its roots in gruelling manual labour.

David A. Walker, who helped develop the pastime into a competitive sport, trace its origins back to ancient Phoenician, Egyptian and Chinese rope makers.

The rhythmic motion of the dual jump ropes swung in opposite directions was similar to that of the rope spinners, who twisted two strands of hemp from a wheel into uniformity using a similar technique. The runners, who were tasked with replenishing the spinners hemp before they ran out had to jump the rope to make their deliveries.

From there, it likely only took a few workers to create a game out of the more enjoyable parts of their labour.

5. Murderball

Unlike the other games on our list, Murderball’s origins are largely unknown. The best theory out there is that the game is a schoolyard phenomena, passed down from one generation of children to the next.

It also goes by a variety of names. A Wikipedia entry claims that Butts Up is the most common name for the sacred recess pastime but it also includes an extensive list of nearly 50 alternatives including; A-ball, Assies Rehab and Tea, Beartrap, Red Butt and Rosies.

However, all those names appear to describe the same game with the same basic set of rules.

The game is played with a ball (usually a tennis ball) on a paved surface against a wall and usually involves a large group of players. When a player’s throw off the wall is caught before it hits the ground, the thrower must attempt to touch the wall before the opposing player can get their throw to the wall.

If a player bobbles the ball and drops it in an attempt to catch a ball, they must also run to the wall to beat an opposing players throw. Each time a player loses to a throw, they receive a letter that can eventually spell out the name of the game.

This is where all the names referencing the buttocks come in. The first player to spell out the entire name of the game stands against the wall as each player whips them in the backside with the ball. Talk about a sore loser.