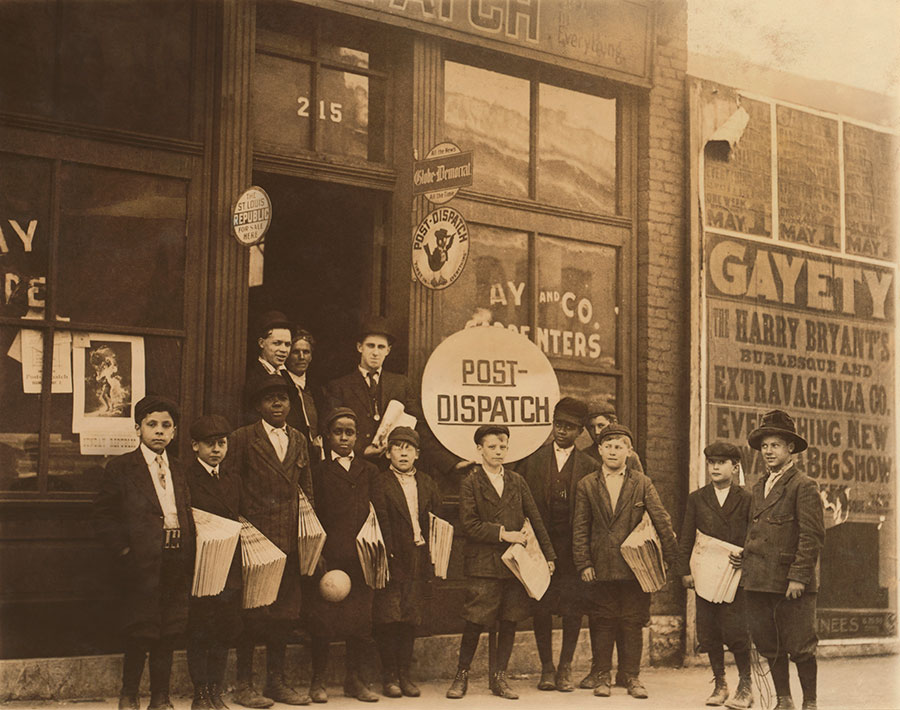

Remembering The Days When the Newspaper Was Delivered by Kids with Ink-Stained Hands

Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/Retrofile/Getty Images

September 4 marks Newspaper Carrier Day, an anachronistic day of remembrance you might want to circle on your calendar along with 8-Track Day and Milk Delivery Day.

Okay, I made up those last two.

But just as we may have trouble explaining to our grandchildren (and, if we’re lucky, great-grandchildren) that we used to kill whole forests every day to disseminate the news door-to-door, we will also have to explain that we had 10-year-olds do the door-to-door part. They then had to go door-to-door again to collect money from their customers, some of whom were deadbeats.

The date commemorates the hiring in September 1833 of 10-year-old Barney Flaherty, the first newsboy, who answered an ad in the New York Sun meant for adults. There is an International Newspaper Carrier Day on Oct. 10, but as near as I can tell, the “international” part is sketchy. British friends tell me there were paperboys in the U.K. But a Parisienne friend, the film critic Valerie Ganne, says that job didn’t exist in France, (though children did often deliver advertising flyers).

My tenure started at 9, when I distributed the small-town (and since defunct) Transcona News. I spent three more years delivering the (since defunct) Winnipeg Tribune. As for the “deadbeat” part, Transcona, now a Winnipeg suburb, was a working-class railway town. I didn’t get stiffed so much as frequently told to come back on payday (hopefully before the client made his way to the local Legion bar to celebrate his paycheque).

It was pretty good money, especially considering that child labour laws didn’t allow for much else. One erstwhile Toronto Telegram “Telly Carrier” recalled that the price in 1969 was 65 cents a week, giving him an almost-automatic 10 cent tip from every customer.

There were prizes for subscription sales (I got a pair of binoculars once), and local sports celebrities sometimes popped by at the newsy meetings with our bosses (yay, Joe Critchlow of the Blue Bombers!).

I was curious, though, when I read about the commemorative day, as to how many people of my generation had been “paperboys” and “papergirls” (yes, there were some, even in those chauvinistic times).

And I was astonished, upon putting out feelers on social media, to find out how many of my Facebook friends, and real life friends, shared my experience.

Scores of people, in their 50s and older, recalled delivering the various Toronto papers (including the since-defunct Toronto Telegram), the Montreal Gazette, the (since defunct) Montreal Star, the Hamilton Spectator, the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, the Kirkland Lake Northern News, the Ottawa Citizen, the Scarborough Mirror, the Mississauga News, the Brockville Recorder and Times, the London Free Press and the Thunder Bay Chronicle Journal (the daily paper that gave me my first byline when I was a 17-year-old high school student).

In the U.K., the paper-kids apparently didn’t work for the papers themselves, but for “news agents,” delivering various London papers. This contrasts with Canada, where there was a spirited competition between carriers for the dailies. Comedy writer and Frantics sketch performer Dan Redican remembers the newsboy taunt, “Smelly Telly, Stinky Star, Globe & Mail’s the best by far.”

Redican was also one of the few who did morning deliveries (6 a.m. to 8 a.m.). Most of us delivered afternoon editions, something to do between school and dinner. In fact, the death of the afternoon editions at most papers was a key factor in the end of the paper-kid era.

Downsides? Newspapers were REALLY popular and full of ads. The Saturday edition of the Toronto Star, especially, was singled out as a killer, often requiring two wagons.

In the tough North End of Winnipeg (my parents moved around a lot), some kids would swipe papers from other kids’ bundles to sell a few on the side. This would often end in a fight.

And things could be tough for papergirls. Margaret, who delivered the Hamilton Spectator, said, “I remember collecting off really nice people in my community, except for that guy who groped me.

“There were two girls in our community that delivered papers, including me. I did it with my older brother, she did it with her younger brother. The guys made it really difficult for her. We’d call it sexual harassment today. Then it was called teasing.”

Indeed, along with the end of the afternoon paper, the “stranger-danger” aspect probably had a part to play in newspaper delivery going from kids to adults. Ironically, in 1982, the same year Ronald Reagan made a public proclamation supporting Newspaper Carrier Day, a 12-year-old named Johnny Gosch went missing while delivering papers. His disappearance remains a cold case.

Add the general decline in the newspaper business as media companies spent this entire century “pivoting to digital,” and it was only a matter of time before adults took over.

Newspaper subscribers (I remain one) are spread farther apart geographically. So, delivery is done by car over a wider area. The drivers work for distribution companies (I saw an ad online seeking delivery people, promising “up to $1,600 a month” in pay), so the same person will end up delivering competing papers. In my case recently, the same guy delivered the three papers I was paying for.

Meanwhile, throughout this decade, industry analysts have predicted 2021 as the year print newspapers die. If you’ve watched media companies conduct business, you might think it was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But for a generation of us erstwhile ink-stained kids, the newspaper business was money in the bank.

This story was originally published in September 2019.

RELATED:

When We Walked a Magic Street: Remembering Toronto’s Summer of Love

Toy Story: 5 Vintage Toys That Never Get Old

Way Back When? The 90s Nostalgia Boom and Why We All Long for a Simpler Time