Attention All Shoppers: With Food Prices Rising, Try Cheaper Substitutes

Photo: AMR Image/Getty Images

The notion that we used to go to the store with a handful of change to buy a sack of food has been turned on its head. Today, it seems, we go to the store with a sack of money and walk out with a handful of food.

Who’s to blame for this inversion? Not the farmers, who are on the receiving end of prices set mostly in world markets. Not the grocery stores that try to position food and sundries for visibility and create some loss leaders to bring in shoppers. Instead, it’s us.

We’re ever more into packaged foods, pre-cooked foods from deli counters, frozen entrees, pre-portioned boxes of ingredients to make meals and inexpensive canned soups turned into expensive stews. Children are coached by television commercials to disdain generic oatmeal and, instead, to choose expensive boxes of sugar-coated starch, and parents go along with the concept that food comes out of boxes or cans, plastic trays ready for the microwave and, of course, bottles of fluids that one can associate with popularity or fun or athletic prowess.

The numbers that illustrate how food gets from the pasture or field to us are, well, a little bit shocking. Inflation drives up the price of food and almost everything else. According to Canada’s Food Price Report 2019, the average family in Canada will spend about $400 more in 2019 than in 2018 because of rising food prices.

What’s behind this trend is not meat and seafood, both of which will be steady or slightly down in 2019. The data, gathered by researchers at Dalhousie University and the University of Guelph, indicate that shoppers in Canada spend 35 per cent of their food budget on prepared and snack foods, which are expected to cost two to four per cent more this year due to rising ingredient costs. It is profitable to turn a steer into lunch. Hormel Foods Corp., a large U.S.-based processor and packager of meat products, reported a one-year return for 52 weeks ended March 31, 2019 — that’s stock price and dividends — of 33 per cent.

We are eating more packaged foods with big markups over costs of production, marketing, shipping, etc., but not necessarily getting better nutrition. The latest version of the Canada Food Guide is heavy on veggies, natural foods and the most natural of beverages — water. Half of the daily plate of foods is veggies and fruits, a quarter is grain products — bread, pasta — and a final quarter is protein sources of which only a tiny fraction is meat. There are no slabs of steak, slices of salami or packaged cereals. It was not always this way.

An early Canada Food Guide, the 1942 edition, for example, made fruits and vegetables side dishes and urged eating beef liver, heart or kidney at least once a week. Today, worries about cholesterol make liver, which is rich in the stuff, a questionable choice. Potatoes and other vegetables were prescribed at one serving a day.

The 2019 guide includes kefir, a fermented grain product, and tofu made from soybeans. Packaged foods other than pasta and maybe unsalted nuts, are not part of the guide. Nor is the concept of snacking, which accounts for 67 per cent of all eating and drinking, according to the Ipsos FIVE Canadian Snacking Nation 2018 report.

Some foods are so wacky that their prices are incidental. Kopi luwak coffee, for example, is made from beans that have been ingested, partially digested and pooped by an Asian civet. Prices are about $200 a pound.

It has a unique taste, to say the least, and illustrates the vast choice on supermarket shelves. Grocery store experts advise that a typical large supermarket has 40,000 to 50,000 items from which to choose.

In stores, product makers battle for shelf space and position with each other and with the stores, which are effectively landlords, that allocate position by visibility so that eye level is better than down below and end of aisle beats lost in the middle of the row. There are lots of products like Cheerios now in many varieties, eggs that can be extra large down to small, brown, white, free-range, cage-free, organic, omega-3 and more. More products beget more shelf space, and that begets sales. The grocery stores make money on this, but so much choice changes shopping to an exercise in will over mind, philosophy and mental health, and all you came for was something for dinner. Instead, you may have gotten bamboozled.

Cheaper food

Michael Pollen, a famous food critic, nutritionist and a gifted writer, has said “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” That reduces food guides and diet plans from the galaxy of brown rice macrobiotic and Scarsdale, paleo and the rest to good sense. Some of his other prescriptions — “If it’s a plant, eat it. If it was made in a plant, don’t.”

There is a bottom line in all this, and it is environmental good will. Much of the world’s methane comes from cows we breed for milk and meat. Not only does each cow release about 100 kg of methane annually by breaking wind, they also consume great deal of food so that they can become steak. Cows bred and tenderly cosseted can become heavily marbled waygu beef at $250 per pound.

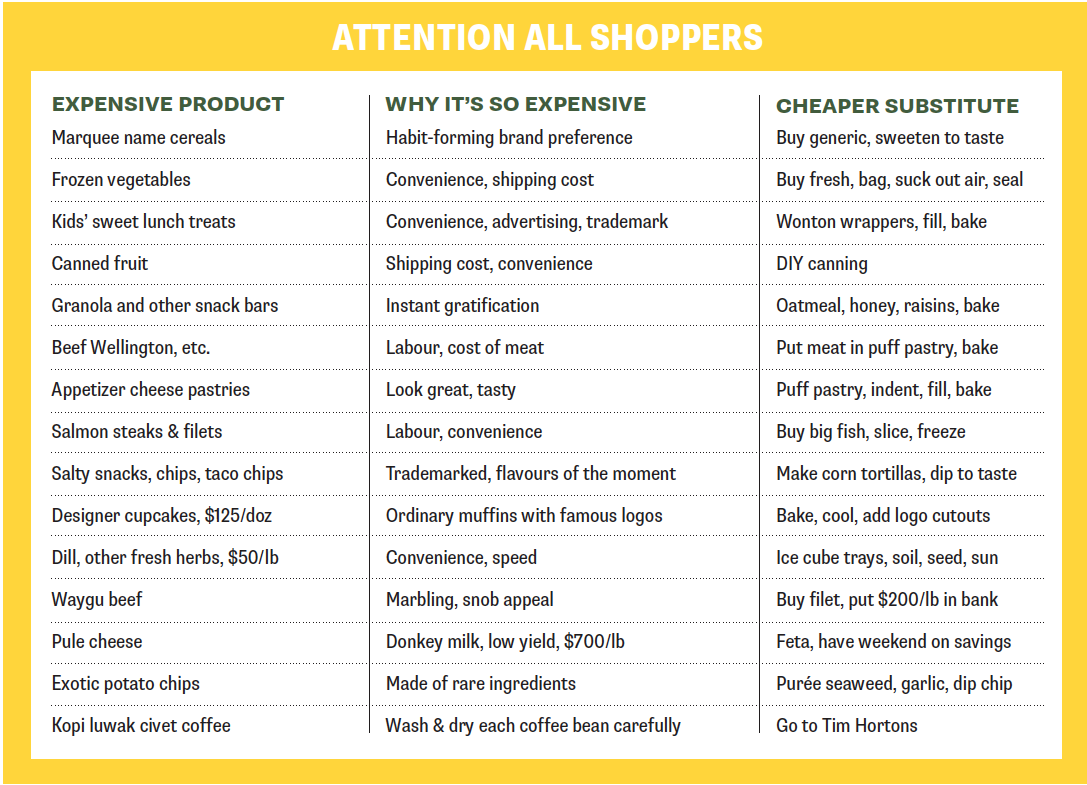

The irony of the rising price of food is that the more you pay, the less nutrition and even good health you may get. Use your good sense to find sensible substitutes that are a bargain for your body, your life expectancy — and your bank balance. Here’s a handy chart to help you get started:

RELATED: