Former Prime Minister John Turner, ‘Canada’s Kennedy,’ Dies at 91

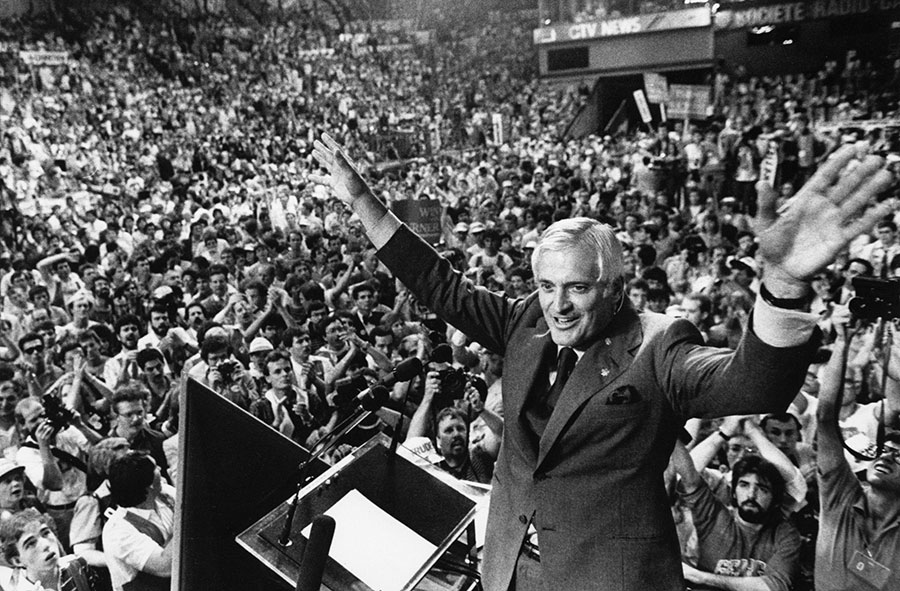

Prime Minister John Turner leans casually on the podium prior to the start of the second nationally broadcasted election debate on July 25, 1984. Photo: The Canadian Press/Ron Poling

In 1984 John Turner became Canada’s 17th Prime Minister. Today, at the age of 91, he passed away. He was a Rhodes Scholar, a lawyer and a career politician – serving as Liberal Party leader, justice minister, finance minister and attorney general. He was Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s lieutenant (and trusted wingman) for many years.

John Turner was one of a kind. An honourable gentleman and an upstanding Canadian, John cared deeply about democracy, equality, and those he served. His optimistic outlook, energetic approach, and tireless service inspired many – and our country is a better place for it. pic.twitter.com/W7n9QsdRUy

— Justin Trudeau (@JustinTrudeau) September 19, 2020

Dubbed “Canada’s Kennedy,” it was confirmed in 2015 that the dashing bachelor had dated Queen Elizabeth’s sister Princess Margaret in the late 1950s. Reportedly they broke up after Buckingham Palace ordered the relationship to end. John Turner was also an elite sprinter who qualified for the Canadian Olympic Team in 1948. Though his tenure as Prime Minister was short-lived – he served for just 79 days before losing the 1984 election to Conservative Brian Mulroney – his passion for Canada was deep and his impact on the country endures.

In June 2014, historian Hugh Brewster explored Turner’s relationship with Princess Margaret. Here is the story published in Zoomer magazine titled “The Princess and the Prime Minister.”

The telegram to John Turner was terse: PRINCESS HAS REFUSED TO ACCEPT ANY EXPLANATION I CAN GIVE OF YOU NOT BEING HERE. The sender was Frank Ross, Turner’s stepfather and the lieutenant-governor of British Columbia. He and his wife, Phyllis, were hosting Princess Margaret during her official visit for the province’s July 1958 centennial celebrations. Phyllis Ross had told the princess about her handsome son, a 29-year-old lawyer and bachelor about town in Montreal, and Her Royal Highness was intrigued. Turner had been asked to fly out to Vancouver to help entertain the royal visitor but had begged off, claiming he was too busy. Yet one did not rebuff Princess Margaret – Frank Ross’s telegram concluded with a virtual royal command: SHE EXPECTS YOU HERE AT LEAST FOR FRIDAY. YOU HAD BETTER COME.

Friday, July 25, was to be the climactic night of the B.C. royal tour, a gala ball hosted by the Rosses aboard the naval reserve ship HMCS Discovery. For this, an attractive young male who could pay court to the 27-year-old princess would be a desirable asset. And Margaret had earned a little fun. Since her arrival in Victoria on July 11, she had dutifully smiled and waved at everyone from cheering Brownies to Cariboo cowboys and had greeted countless civic eminences and their floral-hatted wives. In Nanaimo, she had cut into a 10,000-pound centennial birthday cake with a ceremonial sword; in Williams Lake, she was almost thrown from a stagecoach by bolting horses; in Kelowna, she had opened the Okanagan Lake Bridge while guarded by 140 Mounties because of bomb threats from Sons of Freedom Doukhbors. It had all occurred under wilting summer heat, but Margaret had remained charming throughout, keeping her famed acerbic wit well in check.

The Fairytale Princess was a sobriquet frequently invoked by the B.C. newspapers as they gushed about her luminous eyes, flawless complexion and tiny waist. The weekend colour supplements showcased her clothes, many of them silky pastel creations by royal couturier Norman Hartnell. One exception to the flowery coverage came from the sardonic Vancouver Sun columnist Jack Wasserman, who wrote after following Margaret around for a few days: “I can’t help but feel that this type of life can bring very little pleasure to her.” Wasserman also made a crack about Group Capt. Peter Townsend, a name no one else dared mention.

Townsend Before Turner

Margaret’s romance with Townsend had first become news right after the coronation in June of 1953. She had been spotted affectionately brushing a piece of fluff from his uniform after the ceremony, and the press had pounced. Townsend was a Battle of Britain fighter ace and had the slim good looks of an English film star. On the day he joined the royal household as equerry in 1944, a teenaged Princess Elizabeth had whispered to her sister, “Bad luck, he’s married.” Townsend was divorced by ’53, but the fact that he had been married was still bad luck for Margaret. The Archbishop of Canterbury spoke out against the third person in line to the throne marrying a divorced man. Buckingham Palace did not want any controversy to overshadow the Queen’s pending world tour, so the couple was asked to wait two years until Margaret was 25 and no longer needed royal assent to marry.

As her 25th birthday approached on Aug. 21, 1955, both Margaret and Townsend (who had been exiled to a post in Belgium) were besieged by the press. The public was generally in favour of the princess marrying her dashing war hero, but a few crusty members of Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s cabinet strongly objected. The compromise reached was that Margaret could marry Townsend but would have to give up her rights of succession and any income from the government’s Civil List. On Oct. 31, 1955, Margaret issued a press release stating that “mindful of the Church’s teachings,” she had decided not to marry Group Capt. Townsend. To relinquish being a princess for what one commentator called “life in a cottage on a group captain’s salary” had simply proved too much for her. But the affair had won Margaret some sympathy from her sister’s subjects.

Vancouver was the last stop on Princess Margaret’s B.C. itinerary and since her arrival there on July 22, she had been staying with Frank and Phyllis Ross at their gated mansion in Point Grey. John Turner’s younger sister, Brenda, and her husband, John Norris, were guests there as well.

“We, of course, fell in love with her,” recalled Brenda for Jack Cahill’s 1984 book, John Turner: The Long Run. “She was most entertaining and appealing and, in those days, she was perfectly gorgeous, lots of fun, and we liked her tremendously.”

On July 24, Brenda telephoned her brother and said: “John, look, we’re having this big ball tomorrow night, and Mommy would just adore it if you could come, and she’s worked so hard, so you’ve just got to come. And besides, trust me, you’ll like her.”

John gave in and agreed to fly to Vancouver the next day.

Sexiest Thing on the Squash Court

In late 1950s Montreal, John Turner was “the sexiest thing on the squash courts, the handsomest man at the balls, escorting the prettiest and most eligible girls,” according to Christina McCall-Newman’s book Grits. “I had a lot of action there, mostly French-speaking girls,” Turner confessed to Jack Cahill. The pretty Quebecoises who visited his bachelor pad also helped to Canadianize the Sorbonne-accented French he had picked up while auditing lectures at the University of Paris in 1953, during a hiatus from prepping for his bar admissions in London. Turner had been born in the London suburb of Richmond 24 years before and might have ended up as a British barrister had his English father not died when he was three.

His mother had met Leonard Turner while she was studying for a doctorate at the London School of Economics, and when he died of acute pneumonia in November of 1932, she took John and baby Brenda back to her hometown of Rossland, B.C. In 1934, she moved to Ottawa to join the Tariff Board as an economist, launching a civil service career that would lead to her becoming administrator of the Wartime Prices and Trade Board and Ottawa’s most senior female mandarin. Phyllis sent John to the best Ottawa schools where his progress was accelerated so that at 16 he was ready to enter the University of British Columbia. By then, his mother had married Frank Ross, a wealthy B.C. industrialist who had been recruited as a “dollar-a-year” man to help the war effort in Ottawa.

At UBC, John “carried a gold glow around his head” recalled one of his classmates for Paul Litt’s Turner biography Elusive Destiny. “Chick” Turner, as he was nicknamed, was a track star who broke the Canadian record for the 100-yard dash and would likely have competed in the 1948 Olympics had he not injured his knee in a car accident. The next year, he won a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, where he joined the varsity track and field team captained by Roger Bannister, the first man to break the four-minute mile.

While John Turner was flying out to Vancouver on July 25, 1958, Princess Margaret was on the campus of UBC in cap and gown, receiving an honorary doctor of laws degree. (A real degree would have meant more to her– she always resented the meagre education she had received in palace schoolrooms.) That evening, there were 12 for dinner around the Rosses’ dining table, and it was clear to all present that the princess was drawn to Turner and he to her. “You could see that he thought she was pretty attractive,” Brenda recalled. And when Margaret appeared dressed for the ball in a white silk-satin Norman Hartnell gown with a diamond coronet in her hair, she was simply breathtaking. A film clip from that evening shows her arriving at the ball on the arm of Frank Ross, looking both regal and relaxed with an aura no movie star could match. Ross hands her over to a young military cadet who bows stiffly and then whirls her off in a well-rehearsed waltz. There were six other young men who had been carefully groomed to be her dance partners, and as the Sun’s fashion editor noted, “She laughed frequently … as her partners danced her around the room with her diamond coronet flashing in the soft lights.”

One Enchanted Night

Everyone agreed that Phyllis Ross had outdone herself with the decor. The deck of the Discovery had been transformed into a ballroom for 600 guests with swathes of royal blue and white fabric complemented by urns of white lilies and small arrangements of red garnet roses on the tables. The grounds outside were lit with flaming torches, and the grass beside the water was dotted with glowing white marquees. It was to one of these that the princess retired with John Turner later in the evening, where they chatted, smoked and sipped drinks. Four times, Frank Ross or one of his aides came out to ask them to return to the ball, but each time the princess waved them away. After more than an hour in seclusion, they returned to the dancing. When the princess and her party prepared to depart at 2 a.m., the guests joined in singing “Auld Lang Syne.” As the lights from the princess’s motorcade weaved through Stanley Park, the departing guests concurred with the Sun reporter’s verdict: “There has never been such a ball in Vancouver … [it was] as perfect a memory as anyone could carry for the rest of one’s life.”

The royal party left by train for Banff that Saturday morning as the princess began her cross-country tour. But the press was hot on the trail of the photogenic Canadian who had captivated Princess Margaret. The speculation was that they would meet again in Montreal where Margaret would be on Aug. 5 and 6. In fact, they would reconnect even sooner, at a ball hosted by Gov. Gen. Vincent Massey at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Aug. 2, where they were in each other’s arms for much of the night. This sent the world’s press into overdrive. 3,000 MILES TO DANCE AGAIN WITH PRINCESS ran the headline of the Rhodesia Herald, which claimed (mistakenly) that Turner had flown from Vancouver to Ottawa to be with her, when, in fact, he had simply come from Montreal. TURNER TO DANCE WITH MARGARET AGAIN was the red banner headline atop the front page of the Toronto Daily Star on Aug. 5. The story claimed that Turner would be accompanying the princess to a ball at Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth Hotel on Aug. 6.

Only two days later, however, the Star had another banner headline: MARGARET MISSES BALL, BLAME PALACE ORDER. To the chagrin of its organizers, Margaret had not attended the ball in Montreal, pleading fatigue. Had Buckingham Palace intervened? The notion is not far-fetched – Margaret’s supposed romance with Turner had become the biggest story of her tour. The law offices of Stikeman and Elliott, Turner’s employers, were swamped with calls from all over the world. “What a to-do all that was,” recalled senior partner Heward Stikeman for Jack Cahill. “But John assured me there was nothing to it, absolutely nothing.”

Yet it appears to have been more than just nothing. “Oh, there was no doubt there was a very definite attraction between them … it was a very definite thing …” remembered John’s sister, Brenda. “But I didn’t think anything would ever come of it. John would never want to be in a minor orbit with the royals, and besides there was religion. John was a very strong Catholic.” Marrying a Roman Catholic was as taboo for a royal as marrying a divorced person. And Turner’s Catholicism was not tepid; he had once thought seriously about the priesthood. “If he can’t be prime minister, he can always be Pope,” his mother had once joked to his sister.

Balmoral Weekend

After Margaret returned home in mid-August, the two corresponded by mail, and Turner was invited to Balmoral for a weekend party in August the next year. There, Turner scored a hit with the royal family – he was an amiable shooting companion for Prince Philip and could mix a mean martini for the Queen Mother. He shared a room with a photographer named Antony Armstrong-Jones, whom Margaret had met at a party in February of 1958. She was attracted by his haute-bohemian style, impertinent wit and toothy grin – though she wasn’t certain at first that he was interested in women. Rumours of Armstrong-Jones’s gay leanings have been further fuelled by London interior designer Nicholas Haslam, who maintains in his 2009 memoir, Redeeming Features, that he had an affair with the photographer in 1959. Yet Armstrong-Jones also had relationships with beautiful women. Of his bisexuality, a friend confided in Anne de Courcy’s 2008 biography, Snowdon: “If it moves, he’ll have it.”

Armstrong-Jones was at Balmoral again in October of ’59 when Margaret received a letter from Peter Townsend informing her that he was engaged to a 19-year-old Belgian heiress. “That evening I agreed to marry Tony, “ Margaret later told a friend. “It was no coincidence.” Their wedding on May 10, 1960, in Westminster Abbey was the first royal wedding to be televised and was seen by 300 million viewers worldwide. John Turner attended the ceremony, the only Canadian to be invited in an unofficial role. The English upper crust were snobbish regarding Margaret’s marriage to a photographer, and jokes about “keeping up with the Joneses” lessened only slightly when Armstrong-Jones was elevated to the peerage in 1961 as the Earl of Snowdon. In the early ’60s, the Snowdons represented a younger, cooler brand of royalty, providing a link between the Palace and the world of the arts and fashionable Swinging London. But it was not to last.

In Canada, John Turner, too, was seen as a new kind of public figure for the ’60s. He was first elected to Parliament in 1962 and was soon a rising star in the Liberal Party. Through his sister, he befriended Bobby Kennedy, and many thought Turner would bring Kennedy-style magnetism to Canadian politics. But when Canadians were eventually captured by charisma, it was engendered by an elusive Gallic charmer with a rose in his lapel rather than by the man in the Hathaway shirt. In the 1968 race for the Liberal leadership, Pierre Trudeau was swept into the prime minister’s office while John Turner finished a disappointing third. Yet as justice minister, it was Turner, the committed Catholic, who would shepherd into law Trudeau’s Bill C-150, which legalized abortion and homosexuality. He was at Trudeau’s side during the 1970 FLQ crisis and performed very ably as finance minister from 1972 to ’75. In September of ’75, however, he fell out with Trudeau over wage and price controls and returned to private life.

By then, Princess Margaret’s marriage to Snowdon had dissolved into acrimony. Each of them had found other lovers, and one affair would cause particular humiliation for Margaret. In his memoir, Nicholas Haslam describes how he met “a golden-skinned, auburn-mopped boy” named Roddy Llewellyn in the early ’70s. Roddy soon moved in with Haslam, who helped him develop a career as a landscape gardener. Llewellyn had always longed to meet Princess Margaret so the obliging Haslam arranged for him to be invited to a country-house party where she would be a guest. Margaret, then 43, was instantly smitten by the 26-year-old Roddy, and he quickly became her constant companion. They vacationed together at her house on the Caribbean island of Mustique, and a photograph taken there of the princess and her boy toy in bathing suits was sold to the News of the World in 1976. The tabloids had a feeding frenzy and, within a week, a royal separation was announced. Snowdon moved out of Kensington Palace, and a divorce followed, the first in the royal family.

No longer the fairytale princess in a Norman Hartnell gown, Margaret had become a matronly minor royal – and an unpopular one. Curiously, it would be Canada that would deliver the unkindest cut. While she was touring Alberta in July of 1980, the Edmonton Sun ran a cartoon depicting the princess as a prostitute working a street corner in a low-cut dress and wearing a bracelet with “Roddy” inscribed on it. This crossed a line, and the British tabloids were indignant – it was one thing for them to savage the princess but for the colonials to do so was bloody cheeky. To her friend Gore Vidal, Margaret said philosophically that when there are two sisters and one is the Queen, the symbol of all that is good, it is inevitable that the other will be typecast as the “bad” sister.

John Turner, too, would find it difficult to escape from another’s shadow. He succeeded Trudeau as Liberal leader and became Canada’s 17th prime minister in 1984 – but for only 79 days. In the ’84 election, a Trudeau-weary electorate tossed out the Liberals and handed a landslide majority to Brian Mulroney’s Conservatives. In his stump speech, Mulroney used a well-rehearsed line to characterize his rival as aloof from ordinary Canadians: “When I was driving a truck, John Turner was dancing with Princess Margaret.”

Royal Friendship

Though being known as “the man who danced with Princess Margaret” was not always to Turner’s advantage, he and his wife, Geills, maintained a close friendship with the princess. They would dine with her at Kensington Palace when in London and, as John’s sister, Brenda, remembered, the princess and Turner always “lit up” in each other’s company. Dinner parties frequently ended with Margaret at the piano leading a sing-along, a tumbler of Famous Grouse Scotch and her long cigarette holder always close at hand. While Margaret was on an official visit to Toronto with her daughter, Lady Sarah Armstrong-Jones, in July of 1981, the Turners entertained them at their home in Forest Hill. The head boy (head steward) of Toronto’s Upper Canada College, Tom Heintzman, was invited as a companion for Lady Sarah, in the role John Turner had played for her mother 23 years before.

After his electoral defeat in ’84, Turner stayed on as Liberal leader and was an effective opposition leader, particularly during the ’87 free trade debate. But when the Liberals were defeated again in 1988, he soon retired from politics. In the ’90s, Turner thrived, working with a Toronto law firm and taking summer canoe trips with Geills and his children in the Northwest Territories. Princess Margaret, by contrast, spent the decade fighting illness and disability. She had smoked since the age of 15 and, in 1985, part of her left lung was removed and in ’93 she was hospitalized for pneumonia. A mild stroke in 1998 was followed the next year by her feet being scalded while she was at her house in Mustique, causing her to be confined to a wheelchair. Two more serious strokes followed in early 2001, and on Feb. 9, 2002, she died at the age of 71.

Her funeral at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, was a private service for family and friends, which included John and Geills Turner. They were also Canada’s official representatives at her memorial service in Westminster Abbey two months later. In its obituary, the London Daily Telegraph described Princess Margaret as having been “cruelly exposed to the whims of public opinion.” Others saw her as a tragic, unfulfilled woman, a characterization with which Turner would strongly disagree. “She’s one of the brightest, wittiest women I know,” he told Jack Cahill in ’84. “She’s been a great servant of the Crown … has taken a big load off her sister … has talent to burn … is great on the piano. Yes, she’s good, she’s full value …” Since then, Turner has mostly kept silent about Princess Margaret so it is unknown whether he paid her a last visit before her death. In her final years, Margaret saw very few people and may have wished her Canadian friend to remember her as the beautiful princess she was, rather than the invalid she had become.

As time has passed, Princess Margaret has been considered more kindly. With the 1950s “Margaret look” back in vogue, memories of the glamorous young princess have overshadowed images of the wheelchair-bound older woman. And what better way to remember her than on a warm summer night by the water in Vancouver, laughing with her handsome companion while her diamond coronet sparkles in the moonlight?