From the Ancient Egyptians to Queen Victoria, How the Charm Bracelet Became the Gateway to a Woman’s Personal History

The author’s inherited charm bracelet. Photo: Courtesy of Nathalie Atkinson

My French-Canadian grand-mère Yvonne worked tirelessly into her 70s as head of housekeeping at the Timmins, Ont., Ramada Inn and probably would have been mortified that, of all the mementos available after she died in 2018, I kept her set of work keys. The last thing my grandmother did before leaving the house at dawn every morning was clip a set of the hotel’s master keys to her belt loop, where they jangled and clanked as she moved. I associate them with her brisk walk. Her work ethic. They remind me of the time I spent as a child in the laundry room in the belly of the hotel, helping to fold scalding-hot towels fresh from the industrial dryer.

Much is made of Proust’s tasty madeleines and the primordial power that scent has to transport us back in time, but nostalgia is also triggered by the sight, sound and feel of objects.

The role reminiscences play in our lives is the subject of ongoing academic research and, according to a 2014 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, evoking our past can provide a buffer against loneliness, for example.

In a recent American Psychological Association podcast called Speaking of Psychology, Krystine Batcho, a professor at LeMoyne College in Syracuse, N.Y., explains that recalling cherished memories is a unifying emotional experience. “One example of this is it helps to unite our sense of who we are — our self, our identity — over time.” She contends it’s also a highly social emotion that helps connect us to other people.

In a talk about material culture, Claire Wilcox, the senior curator of fashion at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, emphasized the truth of women’s history lies in the items they handled — even when the objects themselves aren’t considered valuable. “They’re the currency of love,” Wilcox said.

Jewelry, thanks in part to its inherent value, is often handed down as part of a legacy, but the charm bracelet is a treasured keepsake that narrates a woman’s past, present and future. The value is in the deeply symbolic depiction of milestones and memories. Worn for sentiment, luck and protection, the bracelets are life, chronicled and recorded, on a woman’s wrist.

A few years before she died in 2009, my paternal grandmother Dorothy, who lived in Oldham, England, gave me — her eldest grandchild — her double-link, sterling-silver bracelet, weighted down with 17 charms. My grandfather gave her most of the charms: a hinged church that opens to reveal a wedding, a piggy bank as they saved up for a house, a champagne bucket and the wit of a real 10-pound banknote folded up into a tiny, glass-fronted cube, engraved with, “In Emergency Break Glass.” There’s even a Mountie and maple leaf from Fort Macleod, Alta., commemorating my grandparents’ first visit to Canada in the late ’70s. Unlike Yvonne’s keys, Dorothy rarely wore her bracelet and, eventually, not at all, although it would be carefully brought out of its box upon request. Through these tales of the bracelet I learned, for example, how she lost her parents and began working in Lancashire cotton mills at a young age or, prompted by the ornate crown charm, heard about how dazzled she was watching the Queen’s 1953 coronation on TV at a neighbour’s house. I treat the bracelet like a treasure, and also wear it sparingly.

“The charm bracelet is a really specific object that is remarkable yet so pedestrian at the same time,” says cultural historian Wendy Woloson, professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey and author of the 2020 book, Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America. “Their meaning is important and the role they play in our lives is also really important.”

What makes them fascinating as a memory object is that “they’re not tchotchkes you put on your mantelpiece,” Woloson adds. “The charm bracelets are meant to be worn — they’re meant to be public, even if people don’t always wear them.”

“That taps into the very performative aspect of the charm bracelet,” she adds.

“If you do wear it in public, you can explain what it is, enumerating what the charms mean.” The physical object becomes a gateway to personal history. These miniature versions are often utilitarian things, “items from ordinary life that typically don’t have a lot of value, made small and precious — charming,” says Woloson. “Literally, [made] into the embodiment of this idea of charm.”

Vintage charm bracelets can command thousands at auction; kitschy DIY versions crop up on TikTok personalities; and Pandora, the Danish-based international retailer, has popularized a version where charms drilled with holes slide onto round bracelets made of leather, silver or gold.

The heart-shaped and family related charms are the company’s bestselling categories, according to Karen Chisholm, North America vice-president of marketing, and the Pandora Moments line, which features almost 500 charms — ranging in price from a $45 sterling-silver squirrel to a $110 bedazzled, rose-gold-plated Cinderella carriage — accounts for nearly half of the charm business in Canada.

The bracelets gained prestige when royals and movie stars wore charms made by artisans or bought from luxury jewellers. “The mass-produced [versions] play on the cachet of these status objects, of the things that most people can never afford to purchase,” says Woloson. “The Pandora stuff has a psychological value in that it references those higher-end bracelets.”

In his 2007 encyclopedia Jewelrymaking Through History, author Rayner Hesse explains how, thousands of years ago, ancient Egyptians were buried with amulets on wristbands intended to give the gods of the underworld clues about the wearer’s status and position them for the next life.

The more familiar incarnation was popularized among the upper classes by Queen Victoria, who wore gold charm bracelets adorned with small lockets, some of which contained family photos or a snip of her children’s hair. Later that century, fabled Fifth Avenue jeweller Tiffany & Co. debuted its dangling heart charm at the 1889 Paris Exposition.

There is no 20th-century charm bracelet more infamous than the one that figures in the love story of Prince Edward and Wallis Simpson. The Prince of Wales first gave the platinum, Cartier diamond-set chain bracelet to the married U.S. socialite in November 1934, at the beginning of their fateful affair.

Its first charm was a platinum cross engraved with their initials and a private pun but, over a decade, the prince gave Simpson more Latin crosses bearing different gemstones and inscriptions. It caused a stir when Simpson was first photographed wearing it in public in the summer of 1936, because the crosses on the bracelet resembled the pendants the prince wore on a chain. It signalled the seriousness of his intentions — and made her the most talked-about woman in the world. Just months later, Edward abdicated the throne and, the next year, Simpson wore the charm bracelet when they married in France.

The charm bracelet’s mainstream adoption came after the Second World War, when soldiers “would bring home remembrances of places stationed and visited,” Hesse writes in his encyclopedia. “A popular souvenir was a foreign charm or coin, which U.S. jewellers attached to a sweetheart bracelet. Thus, by the 1950s, charm bracelets were all the rage.” They were often featured in portraits of golden-age Hollywood stars, which cemented their appeal. Bette Davis adorned hers with miniature Oscars. Elizabeth Taylor’s appetite for life filled several bracelets with trinkets commemorating everything from movies, children and vacations to lovers and signs of the zodiac. The baubles may be overshadowed by Taylor’s penchant for diamonds, but after her death in 2011, just one of her many charm bracelets fetched more than US$325,000 at auction.

The paradox is that while individual charms are standard, when they are strung together they become invested with unique meaning. However obvious they seem as symbols (diplomas, ocean liners, cameras), their true significance can be cryptic and known only to the wearer.

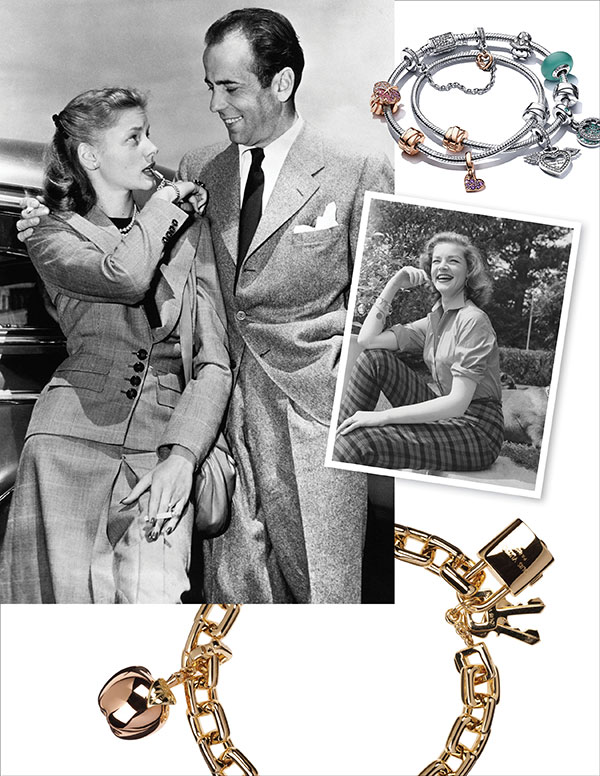

It could be an inside joke, like the functional gold whistle Humphrey Bogart gave to wife Lauren Bacall, referencing the famous line she delivered to him in 1944’s To Have and Have Not, the movie where they met and fell in love: “You know how to whistle, don’t you? You just put your lips together and blow.” Among the charms on Ginger Rogers’ beloved gold bracelet was a feather that dance partner Fred Astaire gave her after filming Top Hat’s famous “Cheek to Cheek” number. He lobbied to have her lavish, ostrich-feather gown changed after it shed plumes onto both the dance floor and Astaire’s immaculate evening clothes, but she refused. The peace offering mended fences and Astaire nicknamed her “Feathers.”

While they are a throwback to continental glamour, charm bracelets have been commodified as a 21st-century fashion item, with Coach and Louis Vuitton both making prefab versions, and Pandora steadily expanding beyond the bracelet format into key rings and earrings that will accommodate the brand’s slider-style charms. The charms themselves have moved beyond tradition to reflect contemporary pop culture with a smiley-face emoji, a slew of Harry Potter characters beloved by the millennial generation, and generation X catnip like Star Wars icon Chewbacca. On Etsy, you’ll find independent artisans crafting 21st-century icons like a pewter pussyhat charm, the symbol of the historic 2017 Women’s March.

Every generation has the impulse to document itself, and the charm bracelet’s renewed cultural currency may prompt a younger audience to craft their own autobiographies — away from the ’gram, and in a form their gran might recognize. These artifacts of a life endure long after we’re gone.

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2021 issue with the headline “A Charmed Life,” p. 70.

RELATED:

Shades of Grey: Celeb Styles to Inspire Your Own Silver Look

The ‘Happy Pill’ Diaries, Part One: Locked Down and Broke in Pandemic Times