Boomers Beyond Borders

Canadian-funded Animal health care pays off in human dividends in the land of a million elephants.

Ridiculous as it seems, when we arrive at the small village outside of Luang Prabang in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, we don’t notice the three elephants browsing in the forest beside the road.

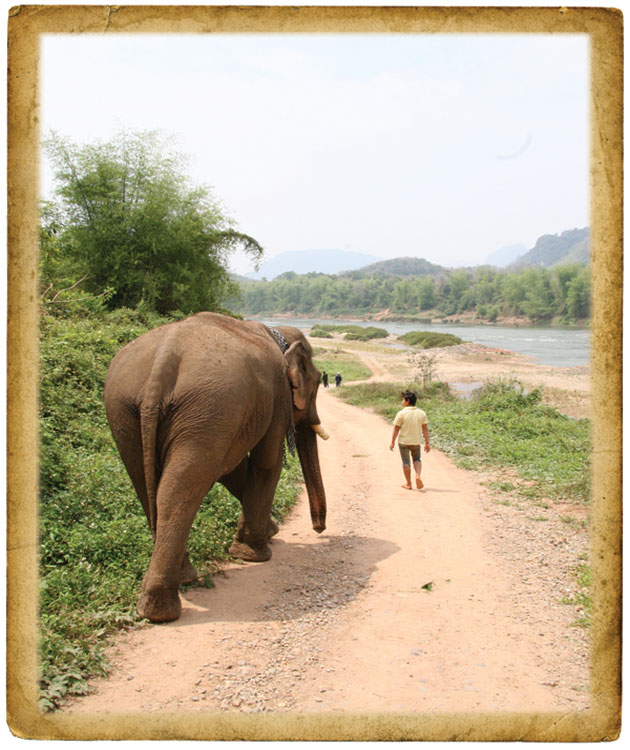

Grey skin matches grey tree trunks so, in spite of their bulk, they’re almost invisible. Dr. Bertrand Bouchard has already parked his mobile vet clinic down by the river, and his assistant is pulling out equipment to microchip, deworm and evaluate the animals’ health. Bouchard is head veterinarian for ElefantAsia, a non-profit group based in France that’s dedicated to the conservation and protection of Asian elephants in Laos.

When he’s ready, the mahouts (elephant handlers) shout commands, and the great beasts pick their way through the trees and trudge down the hill to him. The elephants, a male and two females, range in age from 25 to 35 and will likely work in the logging industry until their mid-40s when they’ll shift to carrying lighter burdens – tourists. Their work and their lives usually end in their early 70s.

Laos was once known as the “land of a million elephants” – presumably a scare tactic since they were used as beasts of war. Whatever their real historic numbers, ElefantAsia estimates there are now only about 800 domesticated elephants and 1,200 in the wild. (Sadly, those made to work logging are helping deplete their wild cousins’ habitat.)

Dr. Anne Drew, 58, of Mosher’s Island, N.S., is observing Bouchard’s rounds to experience examining and treating elephants. She’s near the end of a four-month posting in Laos for the Canadian branch of Veterinarians Without Borders (VWB). Their two organizations are collaborating to promote the use of a more humane elephant saddle – designed at Ontario’s African Lion Safari.

ElefantAsia’s mobile clinic visits working elephants twice a year without charge and rarely allows onlookers. Four of us are there with Drew because VWB is supported by Aeroplan, the loyalty program that lets members earn Aeroplan Miles they can use for merchandise, travel and experiential rewards – or they can give them to Beyond Miles. This program uses member-donated miles that VWB and eight other non-profit groups can redeem for air travel (all carbon-offset by Aeroplan), car rentals and accommodation. In 2011, the charities each received 1.25 million miles.

Drew finally has a chance to use her skill on her biggest patient yet when Bouchard decides one elephant needs a blood test. She pops a needle into a vein in the back of its ear, and blood quickly fills the test tube. The process apparently doesn’t hurt; the animal stands patiently and is later rewarded with a bath in the river. Breastplates used in logging often rub and create fibrous tissue that can become infected so the ElefantAsia vet makes plans to return and drain an abscess on another elephant’s shoulder. The animal will need a few days off work after the procedure, which means no money for the mahout and his family.

Amanda Sital has been discreetly snapping shots since Bouchard and Drew started assessing the first elephant. She and Luis Garcia-Mendez, both Aeroplan employees, were selected by VWB to gather visuals that will show how its projects improve human and economic health in developing countries. Aeroplan encourages employees to apply to travel and be of service to a Beyond Miles partner.

The focus of Drew’s work in Laos, however, is not elephants. She’s training 33 volunteers from 11 villages to provide basic veterinary care through the Village Ecohealth and Veterinary Extension Project, a joint program of VWB and the faculty of agriculture at the National University of Laos near Vientiane, the capital city. Up to 80 per cent of Lao people depend on animals they raise for food, yet there is scarcely any veterinary care available for food animals.

A few days after our ElefantAsia excursion, we step onto a platform perched atop two flat-bottomed canoes and putt-putt across the Nam Ngum River to Thachampa, a village of 300. Farm animals here, we soon see, lead vastly different lives from those in Canada. Cattle, for example, are turned out en masse each morning to forage and now, at the end of the dry season, they are heartbreakingly thin.

In one family’s yard, a water buffalo tries to pull away as its owner struggles to tie it to a tree until it’s vaccinated. Drew’s volunteer Primary Animal Health Workers (PAHWs) are grappling with unco-operative calves that have never been restrained by humans. Suddenly, a small calf bawls in pain, and Drew calmly but loudly points out a less sensitive injection site for the vaccine that a PAHW is trying to administer. This is a training session for the PAHWs, and she has to ensure they do the job properly.

Another VWB effort, that has many village women interested is the introduction of new breeds of chicken that are meatier birds and produce more eggs – a source of food and income. It’s a project that captures the imagination of Christa Poole, manager of external communications for Aeroplan, and Alison Sharp, co-ordinator of community engagement. “What I take away from this journey the most is to go out and raise awareness of what VWB is doing, around the world,” says Poole. “They don’t get the [media] focus that larger charities get.” After they return from Laos, Poole and Sharp create an employee challenge: draw a chicken, and Aeroplan donates $5 to VWB to purchase chickens for Drew’s villages.

But nothing happens without the co-operation of the university, and in a poor country (the most bombed country in the world, thanks to the war in Vietnam), its budget is slim. Faculty members, however, are behind VWB’s efforts and help at the training sessions for the PAHWs. At a meeting at the faculty of agriculture, Drew and staffers present reports while Mr. Chanta, head of the department, listens beneath photographs of Marx and Lenin.

Drew figures it will take about five years for the PAHWs to have enough experience to make really big changes in animal health in the villages. She finds it especially rewarding to work with the animal health workers who have had some training already. “You realize that, over time, it does make a difference,” she says.