Discovering Family History and a Palate for Whisky in Scotland

Harbouring a distaste for whisky stemming from his youth, Will Ferguson discovers family history and his hereditary palate in Scotland. Photo: Evelina Andrews

I have come to Scotland to face my demons — or, rather, demon. Namely, the “water of life” as it is known: Scotland’s celebrated single malt whisky. I have a love-hate relationship with whisky. As the scion of a Scotsman — my father’s family traces its roots through Glasgow all the way back to St. Kilda in the Outer Hebrides — I appreciate its rich history and cultural significance. As a teenage thief, filching a bottle of the finest from the back of my father’s liquor cabinet, I have a decidedly different take.

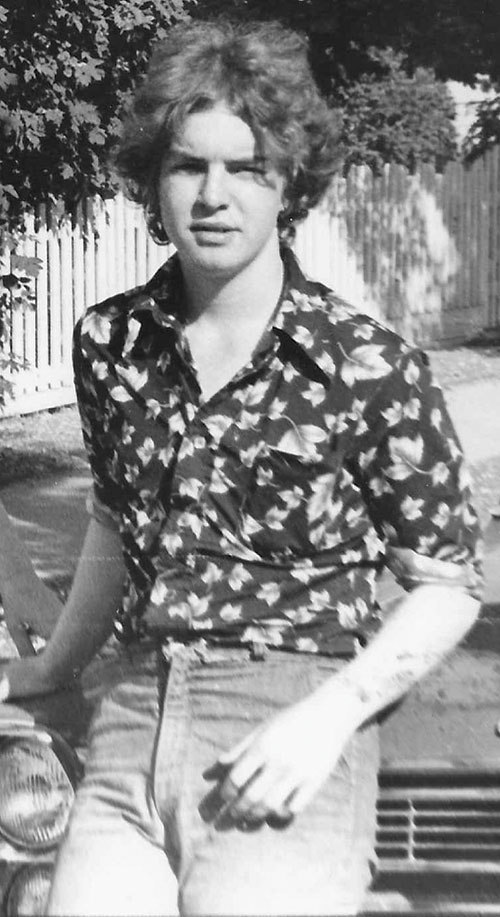

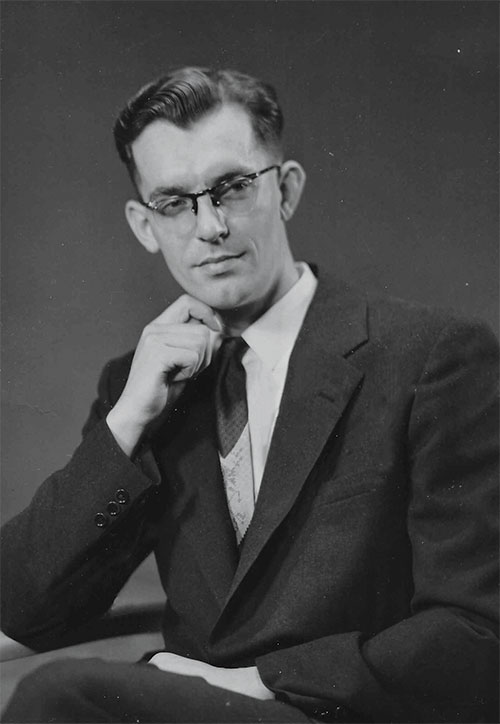

Fayther, as my oldest sister dubbed him, was a great mountain of man with a booming voice and a stare that could melt tar off a roof. He had grown up in the Great Depression, restless and often absent. More importantly, he had a liquor cabinet with a broken lock. The dream of every teenager. Wine and Drambuie and other potions were crowded in front but, at the back, at the very back, where – with impeccable teen logic – I assumed he’d forgotten about it (it had been there for ages!) was a dusty bottle of Glen-something-or-other. The label said it was 18-year old single malt, older than I was when, on the occasion of my Grade 9 graduation, I decided to sneak Fayther’s “forgotten” bottle to the school dance, where my friends and I took turns passing it back and forth behind our small-town gymnasium as the music of Boney M “Ra-Ra-Rasputined” through the doors. We choked it down, wheezing, eyes bleeding. This was to make us look cool and alluring to any girls who happened to pass by. It didn’t work. We eventually finished the bottle, which is to say, got deathly sick.

I remember standing outside our house at the end of the night, retching, as my father looked on, saying tersely, “That was about $20 worth …” – retccch – “That would be about $40 …” – retccch –“That was $30 …”

It never dawned on me that whisky was something one might save and savour. Ever since then, the taste, the smell, even the thought of whisky has caused my stomach to clench.

Never let it be said I am a coward! I have come to Scotland, land of my Fayther, to confront my past head on. I begin in Glasgow, on the banks of the River Clyde.

Glasgow

Glasgow is a city shaped by water, by its river channels and shipyards, its distilleries and docks. The very term “Clydebuilt” refers to something that is innovative, well-made, solid. Today, the shipbuilders are gone, but the

legacy lives on, embedded in the city’s very architecture. Stacey Wallace with Walking Tours in Glasgow – and with a last name like Wallace, you know you are dealing with true Braveheart authority on such matters – points out carvings of the tall ships of the Tobacco Lords entwined above the doorways of the magnificent City Chambers.

With the passing of the ships and the distilleries, Glasgow has reinvented itself of late as an arts and cultural hub, one known for its relentlessly friendly citizens. When I ask Wallace about this, she laughs.

“Aye,” she says. “Friendly to a fault. If you ask a Glaswegian for directions, be prepared. They will tell you their life story and expect the same from you, followed by a detailed discussion of the weather and a list of suggestions for you to see and do, and only then will you get to the directions.”

Whisky and water. The two have defined Glasgow, and the Riverside Museum, an award-winning venue that highlights the full sweep of the city’s shipbuilding and transport past, proudly features an historic 19th-century tall ship tied up out front. The Glenlee is one of only a handful of Clydebuilt sailing vessels still afloat and the only one moored in Scotland. (The others are in Finland and San Francisco.)

Even better, a short walk along the waterfront from the Riverside Museum brings you to the other keystone of Glasgow’s past. The shipyards may be gone, but the distilleries are back. Whisky has returned to the city in grand fashion. The Clydeside Distillery, the first in the city in 100 years, has now opened in a beautifully restored pumphouse. The attached museum includes the world’s first commercial from 1899, a scratchy film loop of poorly kilted Scotsmen prancing about to advertise a local brand of whisky, as well as a film depicting the history of the city, which thoughtfully includes English subtitles with the Glaswegian accents.

I am met by the wonderfully named Bridgeen Mullen, who takes me through my first whisky tasting since Grade 9.

“A simple recipe, really: barley, yeast, water and time.”

Ah, but the devil’s in the detail, and distilling is where science and art meet history and geography. Mullen takes us through each step, from malting to milling to mashing to fermenting to distilling, and the sweet, almost cloying scent of silage envelopes us as we pass by, redolent of the farm silos of my youth.

Single malt, as the name suggests, is not a blended drink. No corn alcohol or other grains. It’s malted barley, pure and simple, and incredibly tricky to refine. We start with a 10-year old Lowland whisky. (The Clydeside’s own aged Scotch is not yet ready to imbibe, so we try others.) “Note the hints of citrus,” she says.

I try to, but memories of Grade 9 keep crowding in. That would $40 worth … That would be $20 …

Next, she pours a dram of Highland, honey coloured with a “long finish and heather honey notes.” We end with a robust Islay whisky, peaty and smoky, with a taste of scorched earth. “Burnt toffee,” as Mullen puts it.

She has us add a “single wee” drop of water in our glass to open up the flavours. I’ve always suspected that tastings work largely through the power of suggestion (“Do you detect undertones of citrus?” “I do!” “And hints of licorice?” “Yes!”). I add more water. An eye-dropper’s worth. Less than a teardrop or two. But still I am fighting the urge to gag.

“Did you enjoy that?” she asks, after it’s over.

“Oh, yes,” I lie, a Canadian through and through.

The Trossachs

If there is a prettier village in this world than that of Luss on the bonny, bonny banks of Loch Lomond, I don’t know of it. Low slate-roofed cottages, gardens bursting with roses, narrow lanes leading down to the clear lake. Canoes are gliding across the surface as a faint mist begins to fall.

“Some might call it rain,” says Graham McIntosh, our kilted tour-guide driver. “We call it liquid sunshine.”

McIntosh is taking us on a journey along the geographic, historic and cultural seam that is the Highland-Lowland divide of Trossachs National Park. Like Glasgow, the rest of Scotland is shaped by its waters, by its lakes, rivers and coastlines. These lochs (pronounced “lauwgchhchhh” as though clearing one’s chest of a particularly stubborn backlog of phlegm; not unlike a Grade 9 student oversaturated in whisky, now that I think of it) are steeped in lore, Celtic and otherwise. Loch Lomond is, of course, the forlorn would-be destination of the condemned soldier taking the “low road” to Scotland. Loch Katrine is the inspiration for Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake. And at Bracklinn, the Keltie River flows out of the Highlands into the Low, a joyous tumble-down affair, its clean, peaty waters falling in a tumult over, around, and under the stone slabs that funnel it through.

An aptly named steamship, the Sir Walter Scott, plies the waters of Loch Katrine, which is, coincidentally, a wellspring of Scottish whisky. “Katrine has soft waters,” Mullen had assured me back in Glasgow. “It carries the scent of the heather.” Onboard, I watch the wooded loch slide past, and it feels momentarily as though I am buoyed on the very waters of life. A lake of whisky before it is whisky. Clean and crisp as the dawn.

Our journey through the Trossachs brings us to Monachyle Mhor, a family-run inn set above Loch Voil with a dramatic rise of Highland hills behind. An art

installation “mirror box” on the shores of the lake reflects the hills and the loch, a perfect metaphor for Scotland it seems.

The traditional five-course meals served at Monachyle Mhor are locally sourced, from the vegetables to the berries to the meat. (The beef, venison and pork all come from within 17 miles of the hotel.) Our first night’s meal included Isle of Mull scallops and halibut from the Isle of Gigha. And the breakfast selections include porridge with the option to add “a nip of whisky.”

The owners of the inn arrange a whisky tasting of their own, inviting a nearby local distillery in to showcase their wares.

Gordon Dallas is an “experiential ambassador” (a job title I’m pretty sure he invented) for Glengoyne, an historic distillery that has been making whisky legally since 1833. Of course, it goes back much further than that,

another 100 years or so, to an enterprising farmer who first figured out how to turn his barley into gold.

Dallas notes my surname approvingly but when I confess that I have, shall we say, an unrefined palate when it comes to all things Scotch-related, he tells me not to worry. “When the whisky hits your DNA, you’ll know.”

We begin with a 10-year old single malt. “Apples, with hints of toffee,” he suggests. I taste Grade 9 grad. Then we try a 12-year-old Scotch that has been aged in bourbon casks. “Vanilla with a hint of coconut.” Again: Grade 9 grad.

But then, with the 18-year-old Scotch, something shifts. Slightly. If not in my DNA, my perceptions. It has an oaky taste and a fiery mouthfeel. And when we arrive, at last, at Glengoyne’s top-of-the line 21-year-old Spanish-casked single malt, the flavours open up. Cinnamon and cloves. “Christmas in a glass,” as Gordon puts it. A word comes to mind: elegant. And slowly, almost imperceptibly, Grade 9 begins to dissolve.

“Enjoy that, did you?”

I did.

The Isle of Arran

We are searching for the White Stag of Arran, which our latest kilted driver-turned-tour guide assures us is real, though I suspect it is the Arran equivalent of Nessie. “Ooo, the White Stag, you just missed him. He was right there!”

Purple clustered thistles in tight bouquets, the emblem of Scotland growing wild and free. Holy Island below, anchored offshore, standing as if on a polished shield.

“I’ve seen the stag, just on the other side of that hill,” he tells us. “There is a white doe as well, on the far end of the island.” Separated by the valleys and heights of Arran: the white stag and his lost love. I feel a Highland ballad coming on.

The Isle of Arran has been described as Scotland in miniature: forested glens, broken peaks, soaring heights, clear-running rivers, its manor house and castle ruins, its cattle grazing on windswept slopes. But there is nothing miniature about Arran. And, although it is south of Glasgow and reached by a ferry from Ardrossan, the island is resolutely Highland. The full saga of Scottish history runs through it, all the way back to Viking invaders.

Brodick Castle, manor home of the Clan Hamilton, is an impressive showpiece. It is also under the auspices of the Scottish National Trust.

The castle itself is haunted. Naturally. In Scotland, a castle without a ghost is like a glass of whisky without undertones of citrus. Dr. Jared Bowers, operations manager, lives in the castle, and he thinks he might know where the ghost stories come from: weather and the wind. “Just stories, of course, but at night? When the castle creaks and groans, you begin to have second thoughts.”

Along the way to Brodick Castle, seals are basking on the rocks – and is there anything more content in this world than a seal sunning itself? The road winds its way along the shorelines and rivers and over the heights to Arran’s northern shore, where an older 13th-century castle ruin stands guard. Which brings me to my final tasting of the trip: at the Arran Distillery, home of the island’s gold-medal winning whisky. Yes, there are medals for whisky and, yes, Arran has taken gold.

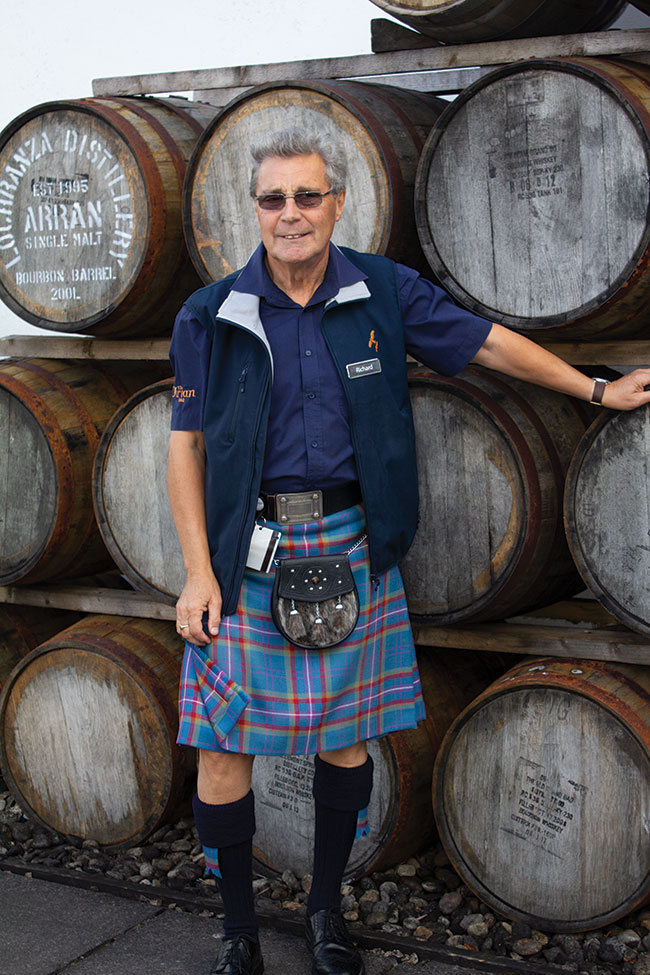

Richard Wright of the MacIntyre clan leads our group past the distillery’s copper stills. This is where the alchemy occurs. A warm, yeasty smell welcomes us like bread dough rising, like porridge simmering on a stove.

We begin with their flagship 10-year-old single malt.

“It’s all about the water,” Wright says, and he should know. He is wearing a kilt, after all. (If there is anyone you can trust when it comes to whisky, it’s someone who is wearing a kilt.) “You can’t replicate it. Scottish water is soft and heathery. The key to Scottish whisky is Scottish water.” One might say the same about Scotland as a whole. He pours. We let it breathe, nose it, swirl it, watch it coat our glass like olive oil. It should, he tells us, take a good 15 minutes to enjoy a single nip of whisky.

“Don’t throw it down your throat and then cough and choke and pretend it’s good,” he admonishes. “You don’t drink whisky. You taste it. Should study it. Sip it. Enjoy it. Think of your tongue as a sponge.”

Oh, my poor teenage self, if only you’d come to Scotland before you pilfered your father’s treasured Scotch!

And then … he pours us a tumbler of Arran Gold, a locally concocted whisky liqueur, and it happens. The heavens open, the angels sing, the sun pours down like honey. A smooth, creamy drink with plummy undertones. And there it is. The waters and rivers, the heathers and lakes. The gold of Scotland. Land of my Fayther. It was all of it contained in that single glass, that single moment.

Wherever he is, my dad would be proud.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2020 issue with the headline, “The Waters,” p. 79.

For more information on travel (and applicable restrictions), check VisitBritain.com or VisitScotland.com.

RELATED: