Director’s Cut: Martin Scorsese Talks ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’ His Early Career and the Future of Cinema

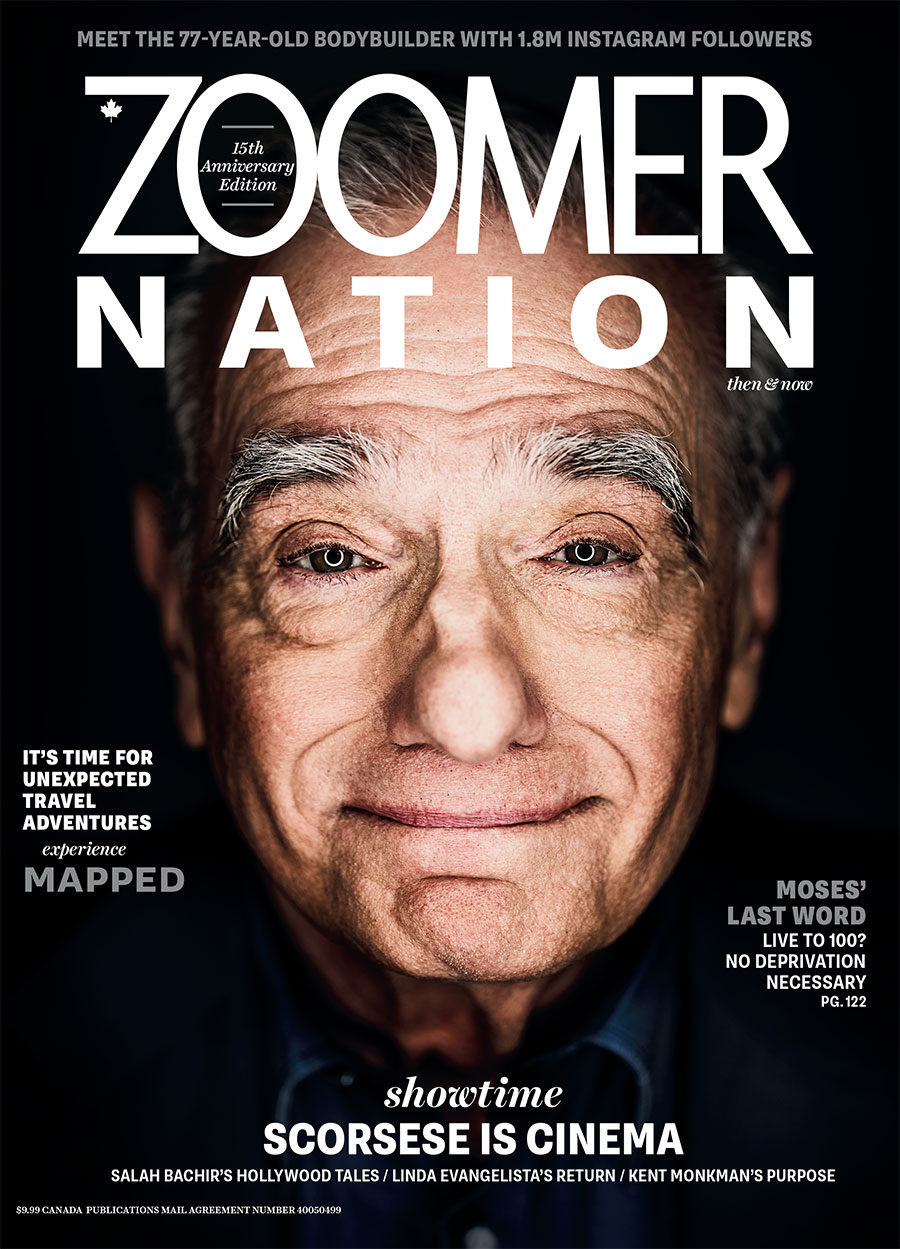

In Zoomer magazine's Oct/Nov cover story, Martin Scorsese — pictured here in his hometown of New York — speaks about his career and latest film, 'Killers of the Flower Moon.' Photo: Mark Mann/August

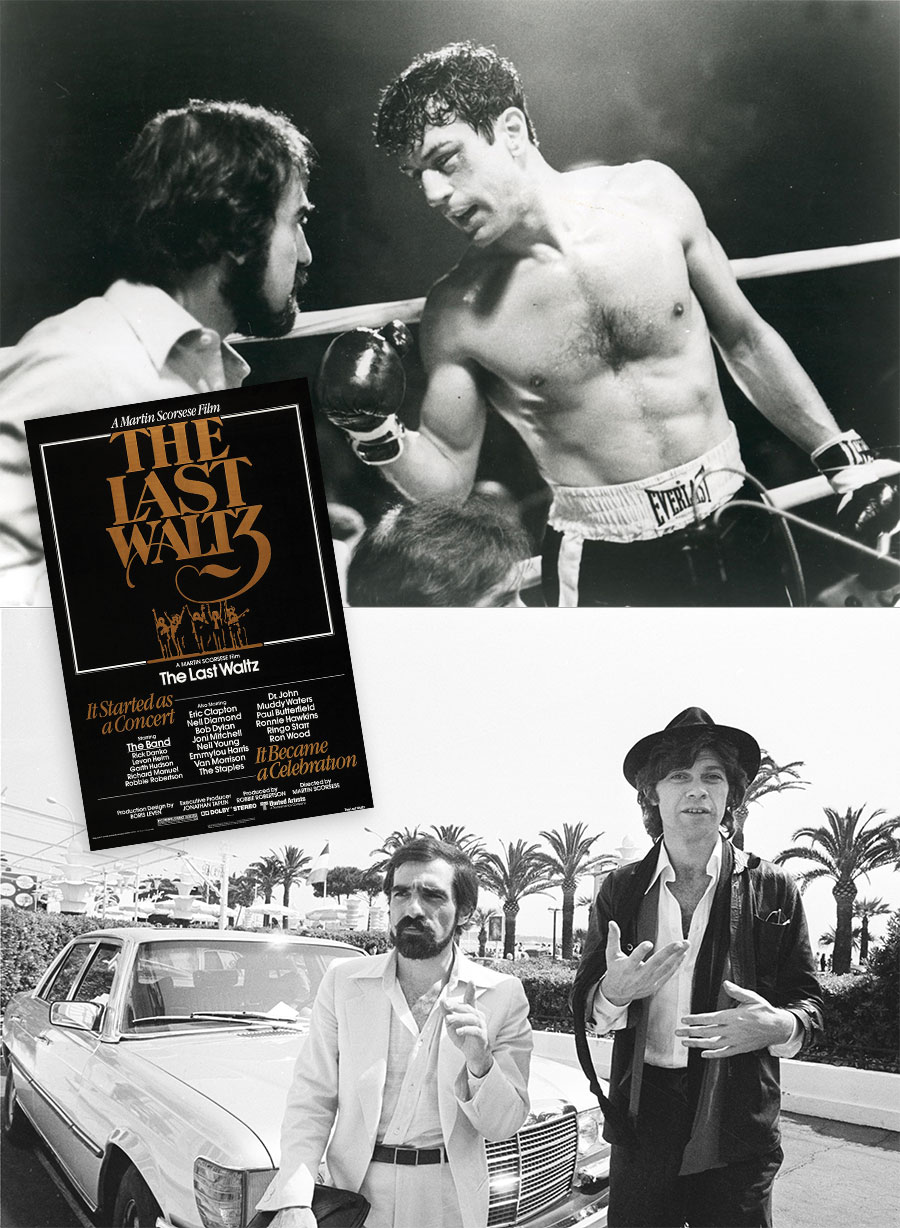

In The Last Waltz, Martin Scorsese’s documentary about The Band’s farewell performance, the director interviews Canadian songwriter and lead guitarist Robbie Robertson. It’s 1976, after Scorsese had won the Palme D’Or in Cannes for Taxi Driver and picked up his camera to film the legendary rock band’s last performance in San Francisco.

Robertson is in his trademark look: leather jacket, with a shirt unbuttoned enough to tease some chest hair. He tells Scorsese he wanted the performance at the Winterland Ballroom, which The Band dubbed The Last Waltz, to be a celebration. “Celebration of a beginning or an end?” Scorsese asks, to which Robertson responds, “Beginning of the beginning of the end of the beginning.”

Robertson’s words hit a different note today. The Toronto-born rock ’n’ roll legend, who was half Jewish and half Indigenous (his mother was Cayuga and Mohawk), died on Aug. 9, at 80. His collaboration and lifelong friendship with Scorsese, who turns 81 in November, was just beginning when they made The Last Waltz, a mournful documentary commemorating the music and friends The Band made on the road, and the “impossible way of life” that Robertson felt compelled to end. The musician went on to reinvent himself as a solo artist and composer, writing scores for many of the director’s marvellous films, like The Color of Money and Silence.

Scorsese’s latest epic, Killers of the Flower Moon (in theatres Oct. 20 and streaming later on Apple TV+, which funded the film), is a grisly and graceful period piece about violent crimes committed against an Indigenous community in Oklahoma. The director tells this foundational story, where America’s original sin is on repeat, alongside his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker, 83, with muses Robert De Niro, 80, and Leonardo DiCaprio, 49 in November. Killers marks the sixth Scorsese film for DiCaprio and the 10th for De Niro, but it’s the first time the two actors have worked together on a feature with the master filmmaker.

Scorsese also reunited with Robertson, who spent summers at his mother’s community on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve near Brantford, Ont., where he developed his interest in music. For Killers of the Flower Moon, he composed a haunting percussive score with tribal drums, whistles and acoustic strings that tug at the soul. It’s some of Scorsese and Robertson’s finest work together; it’s their last waltz.

“Robbie Robertson was one of my closest friends, a constant in my life and my work,” Scorsese shared in an Instagram post in August. “There’s never enough time with anyone you love. And I loved Robbie.”

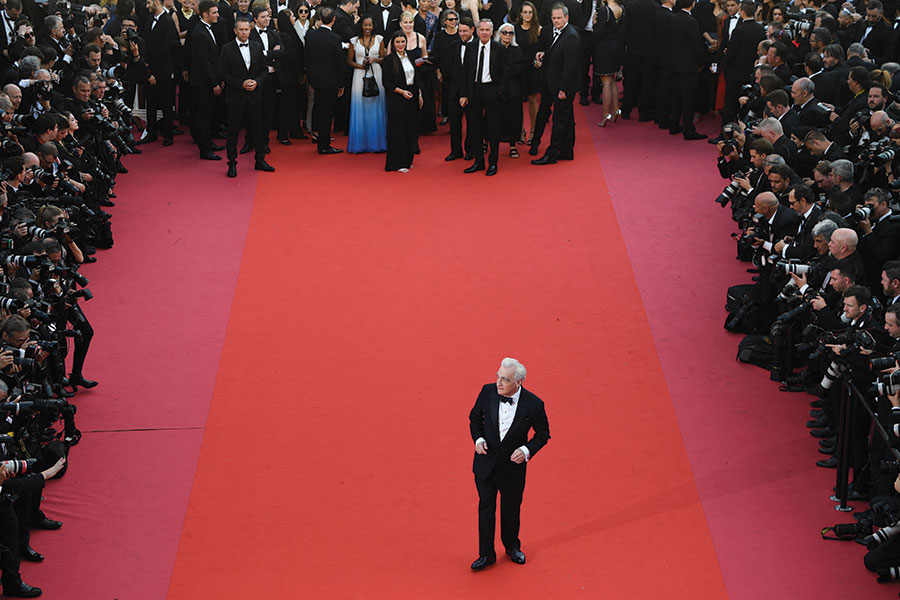

The same mournful but celebratory mood Scorsese captured in The Last Waltz is in the air at the Cannes Film Festival in May, where Killers is having its world première. The excitement over the arrival of a new Scorsese picture is tempered by the sobering realization that the director only has so many left. Days before the premiere, the Hollywood trade paper Deadline published an interview where Scorsese says, “I’m old. I read stuff. I see things. I want to tell stories, and there’s no more time.”

His previous film, 2019’s meditative crime epic, The Irishman, only adds to that sense of impending finality. It’s a swan song — reuniting Goodfellas and Casino stars De Niro and Joe Pesci — about the purgatory that awaits gangsters who somehow survive the business, living with their sins as they wait to die, and contemplating their legacy when they’re almost out of time. It might have been a perfect note to go out on, but retirement is not in the cards for Scorsese, who shows no signs of slowing down.

In April, he was spotted on a New York subway car directing hot young talent Timothée Chalamet, 27, in a commercial for Bleu de Chanel fragrance. Currently, the director is prepping his next projects: an 18th-century shipwreck drama starring DiCaprio called The Wager, based on the 2023 novel of New Yorker writer David Grann, and an adaptation of Pulitzer Prize-winning American author Marilynne Robinson’s book, Home, about a minister’s son who visits his hometown in Iowa at the beginning of the civil rights era. “It’s just interesting about the minister and what he stands for,” Scorsese teases.

The fast-talking director is sitting in front of me, wearing a climate-appropriate, sand-coloured blazer over top of a purple shirt with the top button undone. Everything looks so big on Scorsese’s tiny 5-foot-three frame, from his shirt collar to his spectacular salt-and-pepper eyebrows, but his presence feels immense. For a room full of cinephiles weaned on Raging Bull and After Hours, Scorsese is a god, even though there’s nothing about his humble and playful demeanour to indicate that he holds himself in such reverence.

We’re in a penthouse suite at the L’hôtel Barrière le Majestic, which overlooks the Cote d’Azur, a couple days after the Killers première. The day before, I spoke to Scorsese’s cast members De Niro, DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone, 37, and Jesse Plemons, 35, during a series of roundtable interviews. Now it’s Scorsese’s turn to answer for his movie, his legendary career and an industry that is either shifting or crumbling, depending on your perspective.

“Don’t you think that now, the cinema of the past hundred years or so, it’s gone, in a way?” Scorsese asks in response to a comment I make about his daughter, Francesca’s, TikTok. (I actually assume Francesca, 24 in November, is his granddaughter, and Scorsese lets out a lively chuckle as he corrects me.) I bring up social media because Scorsese occasionally makes fun cameos on Francesca’s TikTok channel. Considering how much energy he has expended preserving old films and cinema-going traditions, I find his embrace of social media pleasantly surprising.

His good friend De Niro — who grew up alongside Scorsese in the same Little Italy neighbourhood — just flat-out tells me he doesn’t do the internet. “I don’t listen. I don’t want to watch. I don’t want to know. It’s too much,” says De Niro, worrying about how so much negativity online affects mental health. “My general impression is that it’s hurt a lot of people in certain ways.”

Scorsese, on the other hand, sees promising young talent on apps like TikTok. A new generation is wielding smartphone cameras to capture fun long takes and figure out comic timing through performance and edits in videos that last 15 seconds to three minutes.

“The thing is, it’s a new language,” he says, “and the future is there. The future is in the young people. But what are they going to say is the key? Can and will there be room for young people to express themselves in more than two hours?”

Scorsese is dwelling on comments about Killers of the Flower Moon that focus on its three-and-a-half-hour duration. In a review, Variety critic Peter Debruge suggested it “isn’t an epic motion picture so much as a miniseries.” Scorsese, annoyed at the suggestion, retorts, “No, it’s a film,” during our interview. “I don’t know if they’re critics,” he adds, wondering if the people who suggest his storytelling belongs on TV are paying attention to the images he puts on screen and how cinema functions. “Do they analyze cinema, or are they analyzing and reacting to our modern world, really?”

Scorsese is expressing frustration with an industry that relegates thoughtful dramas to the small screen. “It’s enough,” he yells, banging his fist on the table, playfully performing the grumpy old man. He’s joking, but he’s also sincerely concerned. At home, mature audiences are mostly served by series like Succession and Better Call Saul, while movie theatres are a playground for franchise fantasies. That was the root of his infamous complaint in 2019, when he declared Marvel movies are more akin to theme parks than cinema. “The studios, this is what they’re making,” he says, “because the theatres cost money to keep alive, and those films bring in the money.”

The big difference between Scorsese’s films and the franchises he rails against is that the latter tend to be spectacles that lazily satisfy an audience’s expectations by sticking to formulas and algorithms. Meanwhile, Scorsese’s whole canon provokes, challenges and takes big risks.

Scorsese was part of a wave of game changers called The Movie Brats. They emerged in the ’70s from film schools — in his case, New York University — and used their deep knowledge of classic and international cinema to shake up Hollywood, after Dennis Hopper made Easy Rider. The influence of the counterculture brought the ’60s studio system of movie-making to its knees.

“I’m not a hippie,” Scorsese clarifies, explaining that he admired some of their ideals, but wasn’t really part of the scene. He also points out he was an assistant director on Woodstock, Michael Wadleigh’s iconic 1970 documentary about the four-day music festival, where he stuck out like a sore thumb in that free-spirited environment. “Me being at Woodstock, on the stage, for four days and nights with all the hippies and everything. I had cufflinks. I didn’t know.”

Scorsese’s earliest work includes his 1967 feature debut, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, about a Catholic man (Harvey Keitel) torn up about his sinful relationships, and the Roger Corman-produced exploitation flick, Boxcar Bertha. They’re scrappy, sexy and provocative dramas, and introduced the filmmaker’s lifelong attempt to reconcile the sacred and the profane.

Spirituality — its purpose and mystery — casts a large shadow over the career of the former altar boy and seminary student, who can cite classic films like scripture. His characters, whether they are from the streets of New York or Bethlehem, are often conflicted in their pursuits of holiness and pleasure. Scorsese made films about criminals — like his break-out movie, Mean Streets, and The Departed (for which he won his only Oscar for directing) — and religious figures — The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun — all of whom are wracked with guilt. He stops and starts his sentences as he struggles to articulate what he wants to say about living with spirituality and sin. “If you’re blessed in a way that you can create some kind of art,” he concludes, “you try to get to a simplicity of it. And then maybe that simplicity, maybe that is existence, and that’s what a life means.”

Scorsese’s most recent movies are longer and more contemplative; every frame counts toward a greater purpose. The 2016 film Silence, which is about Jesuit priests in Japan who unintentionally bring suffering instead of salvation, is arguably his masterpiece, and the fullest expression of some of his lifelong pursuits.

Scorsese’s growth also includes an eagerness to tell even more diverse stories, not that his perspectives have been narrow. The director has long been a fierce champion of international cinema and established the not-for-profit World Cinema Project to preserve neglected films from countries like Senegal and Cameroon. His movies may overwhelmingly star white men — often with a critical look at their racism and misogyny — but his support of films and filmmakers from around the world is tireless.

In the past, Scorsese was hesitant to tell stories about other cultures, especially since he came from “an enclosed little village in New York that could have been Sicily.” The director was famously attached to Schindler’s List before passing it over to Steven Spielberg, because he felt his friend’s Jewish perspective would be more intimate and appropriate.

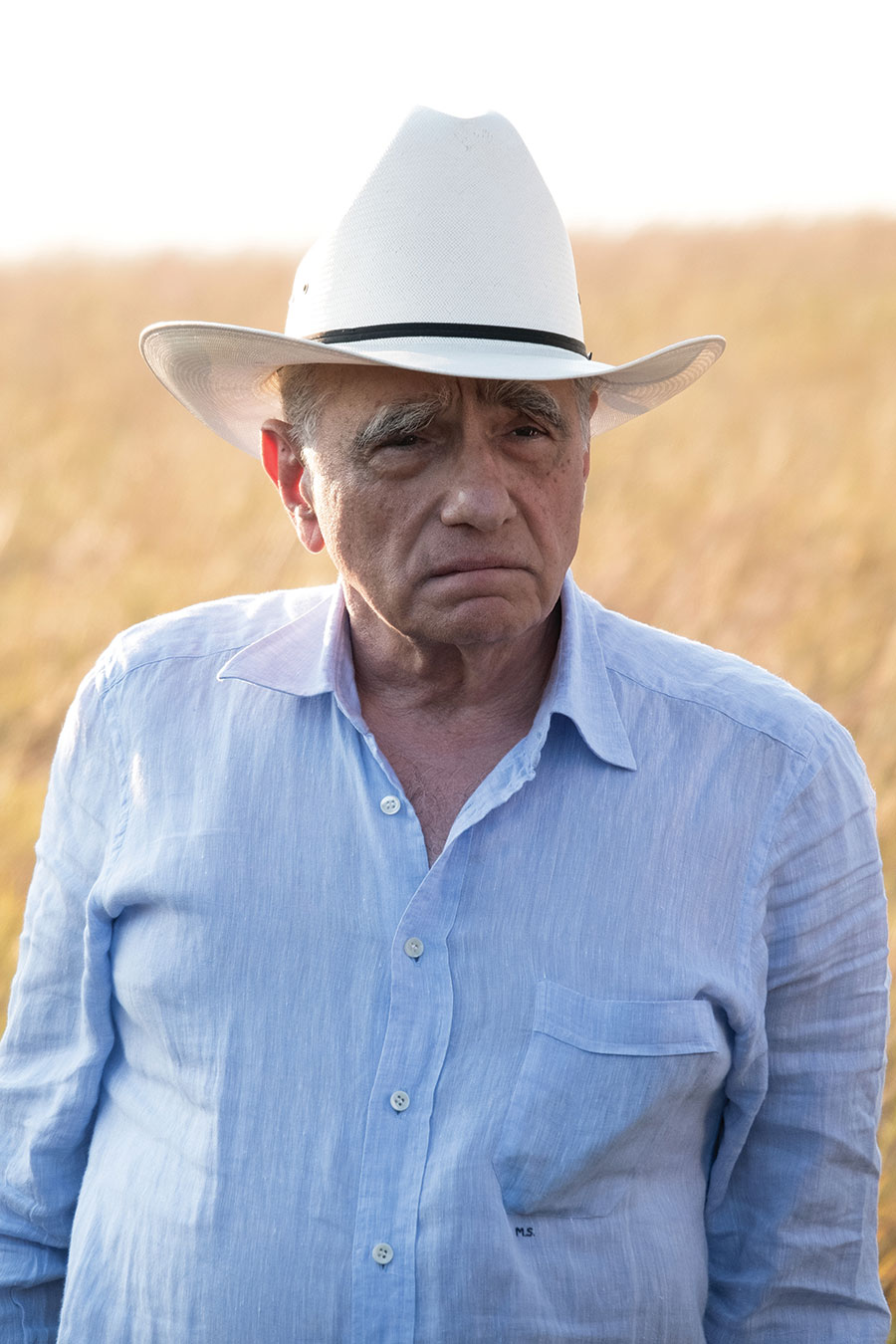

That same respectful caution informs Killers of the Flower Moon. “I was very nervous about it,” says Scorsese, who understands how movies directed by white men have misrepresented Indigenous communities. “I had some experience with Native Americans in the mid-’70s. I went to Pine Ridge [for the occupation of Wounded Knee by the] American Indian Movement. I was just not prepared for what I saw. I was shocked by how much I didn’t know.”

“The respecting of other cultures and other people, that’s the whole key,” Scorsese continues. His pursuit of truth and authenticity motivated the decision to shoot Killers in Oklahoma’s Osage County, which is the setting for the movie, and enlist community members to work as actors, crew, language consultants, costumers and more. “I said, this is going to be with the utmost respect and as much understanding of who they are; not only who they are now [but] who they were then, [and] who they were before then.”

Scorsese’s latest film is based on Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, a 2017 non-fiction book by Grann. The Osage, who amassed incredible wealth at the turn of the century from oil on their lands, became the richest community per capita in the United States. The reservation was filled with luxury furs and sports cars, which became a prime attraction for vultures. Sixty or more Osage members were murdered between 1921 and 1926, and those deaths were plotted by the white men who married into Osage families to inherit their wealth.

The investigative journalist’s book follows the newly formed FBI’s investigation into the Osage murders, and DiCaprio, a producer on the film, was originally set to play the book’s hero, Tom White, the Texas Ranger turned federal agent who eventually solved the crimes. But, after extensive consultations with the Osage Nation, Scorsese overhauled the script, co-written with Eric Roth, ditching the mystery and focusing instead on a complicit society finding ways to extract an Indigenous community’s resources. “It’s not a whodunnit,” Scorsese says at the Cannes press conference the day before our interview. “It’s, who didn’t do it?”

The film lays out an intricate ecosystem that enabled white men and their associates to commit their crimes, with local politicians, police and lawyers facilitating the theft of the Osage Nation’s wealth. “How complicit can we all be, if we’re tested?” Scorsese asks. “It’s about who we are as human beings. We get a little comfortable. We get this way.”

DiCaprio describes the script overhaul as a “two-part process.” The first involved shifting his role, and the film’s focus, from the FBI agent (played by Plemons) to the sniveling Ernest Burkhart, a First World War veteran and grifter who, under the influence of his uncle, William Hale (played by De Niro), conspired to collect Osage fortunes. “Until we got into Oklahoma and actually really listened to these stories and saw how people continue to be affected, we didn’t quite grasp it all,” DiCaprio says. “It is a microcosm for things that are still happening today.”

DiCaprio has a surprisingly booming voice. Even as he speaks softly, the bass seems to fill the room. But the actor defers to his co-star Gladstone, who plays Ernest’s wife, Mollie Burkhart; she is seated beside him, her light-blue eye shadow matching his eyes. The most heartening sight at Cannes – from the premiere to the press conferences to the hotel room interviews – has been watching Gladstone, who is of Blackfeet and Nimíipuu heritage, owning her space while flanked by cinema giants Scorsese and DiCaprio.

Gladstone is comfortable enough to correct DiCaprio at the press conference when he describes their approach to Osage culture and history as “anthropological.” “I kind of put you on the spot earlier when I said this,” Gladstone says, turning to DiCaprio during our interview, “but it’s important in storytelling, especially working in communities, to try to be a little less anthropological.”

She’s referring to a history of settlers who have treated Indigenous communities as something to be “studied.” An obvious example is Robert J. Flaherty’s Nanook of the North, the 1922 film largely considered to be the first documentary feature, despite staged and inauthentic scenes. Alternatively, Gladstone says, DiCaprio and Scorsese were just being empathetic humans and allies when telling the Osage Nation’s story.

Gladstone is a shrewd and heartfelt performer and activist who had her breakout role in Kelly Reichardt’s quietly powerful drama, Certain Women, and is now being touted for Oscar recognition for her commanding performance in Killers. In the film, and in conversation, Gladstone has the kind of gaze that simultaneously appears to embrace and look right through you. After the rewrite, Mollie rightfully became a main character. Her perplexing and heartbreaking marriage to Ernest, who has a hand in murdering her family, becomes analogous to a broken treaty. “Mollie just provided this endless wellspring of unconditional love for somebody that didn’t really deserve it, but kept taking,” Gladstone explains. “That’s the extractive nature of colonized land.”

DiCaprio and Gladstone wrestled with their characters and searched for ways to make the relationship believable. “It boggled my mind how she stuck with him through that entire tragedy,” says DiCaprio. During our interview, they volley the conversation back and forth, still struggling to understand Ernest’s duality and how Mollie could be deceived by him. DiCaprio references a video where Ernest, then 82, speaks lovingly of Mollie while still denying his own greed and involvement in the crimes. While they puzzle over the mystery of it, Scorsese gets to the heart of it, and suggests Ernest is a blatant example of how a colonizer’s mind grapples with guilt. “‘I’m not complicit in this,’” Scorsese says, performing his take on Ernest. “‘All I did was tell John Ramsey to go get Asa Kirby to blow up the house. I didn’t blow it up.’”

Never mind De Niro and DiCaprio. The more momentous generational passing of the torch in Killers is between Cree and Métis actor Tantoo Cardinal, 73, and Gladstone, two Indigenous women who continue to make a difference on-screen.

Cardinal — a member of the Order of Canada who has won an Indspire Award for the arts, a Gemini, and a Governor General’s performing arts award for lifetime achievement — took intensive Osage language lessons to play Lizzie Q, mother to Gladstone’s Mollie. She only appears in a handful of scenes, but she leaves a striking impression as an elder with an interrogating stare that discombobulates DiCaprio’s Ernest. Cardinal is in the kitchen of her Los Angeles apartment, wearing a white shirt covered in a floral pattern and letting her long black hair down as she talks to me over Zoom about the tightrope she has walked in the entertainment industry. She made her first feature film opposite Gordon Tootoosis in a 1978 biopic about Marie-Anne Lagimodière, the first woman of European descent to settle in Western Canada. Cardinal played an Indigenous princess in a small role that perpetuated a few demeaning tropes. The actor is intimately familiar with how film and television has misrepresented Indigenous communities while holding up white supremacy.

“I was questioning whether I really should pursue [acting] or not,” says Cardinal, describing the struggle to express herself, given the limited roles available. “One of the jobs that has to be done is to pronounce that I am alive; I have a brain; I have access to emotions.” Over her nearly 50-year-long career, Cardinal has given heartfelt performances in historical docudramas like Places Not Our Own and Indigenous stories like Smoke Signals. Along the way, in movies from Bruce Beresford’s Black Robe to Killers of the Flower Moon, she’s been able to keep nudging the storytelling to better reflect Indigenous cultures. “My contribution to Killers is this perspective that we carry on,” says Cardinal, explaining she asked Scorsese to include a moment at Lizzie Q’s funeral where her ancestors’ spirits escort her to the afterlife. “That’s fundamental to our way of belief.”

Cardinal made her first trip to Cannes for the Killers première, where she proudly wore a majestic flowing black-and-white ball gown with feather patterning by Native American designer Patricia Michaels. “That’s the way to hit Cannes,” she tells me. “Get yourself [in] the hot movie of the festival, ride in on it.”

In Cannes, a movie’s success is often measured by the length of the standing ovation. The applause for Killers of the Flower Moon begins as soon as the credits rolled. At one point, the clapping follows the rhythm of the Indigenous drums on Robertson’s soundtrack. I watch from the balcony as Scorsese and his collaborators stand up to acknowledge the applause, which, after a three-and-a-half hour movie, seems like it is going to go on forever.

I don’t have a stopwatch handy, but the applause reportedly lasts nine minutes. The only reason it ends is because Scorsese grabs a microphone to thank everyone involved in the film, beginning with the Osage Nation. He intentionally cuts the ovation short, allowing some of the tired people around him to grab a seat.

Scorsese simply didn’t have the time for it.

A version of this article appeared in the Oct/Nov 2023 issue with the headline ‘Director’s Cut’, p. 44.