The O.J. Effect: From Cable News to True Crime, How the O.J. Simpson Trial Reshaped Popular Culture

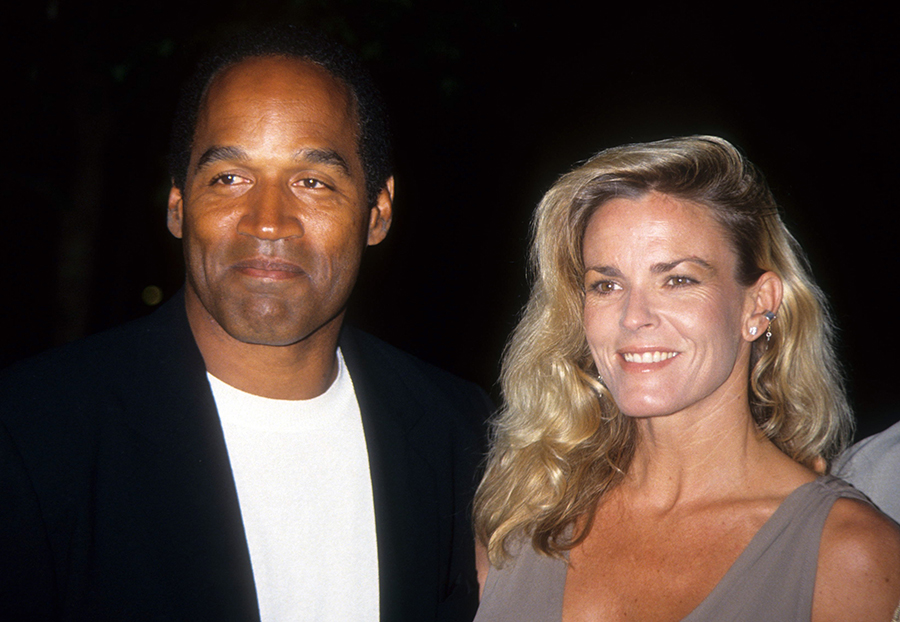

O.J. Simpson, seen here in 1994, leaves the court where he was charged with - and later acquitted of - the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman. Photo: Ted Soqui/Sygma via Getty Images

When did regular folks become forensic evidence experts, chiming in on social media with their takes whenever a high-profile case or true crime doc enters the public consciousness?

I’d wager it began with the O.J. Simpson murder trial.

For months, millions followed the 1995 trial, when O.J. Simpson, who died last week at 76, was on the stand for murdering his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ron Goldman. They tuned in live on Court TV or caught nightly recaps on CNN, parsing the DNA reports, tainted handlings, improper protocol and – perhaps most famously – glove sizes, fortifying positions that ultimately cut across racial divides.

This was the trial that would feed our appetite for procedurals like Law & Order (which got a ratings bump after the murders) along with 24-hour news coverage and non-stop analysis. Talking heads incessantly weighed in on a case that held multiple truths, not just about O.J. but the world we live in. We’re still peeling back the layers today of what became a referendum on race in America, a complex case study on the role skin colour plays in both the pop cultural space and the justice system.

The line most associated with the trial comes from defence lawyer Johnnie Cochran’s summation, when, in reference to an incriminating blood-stained glove, he uttered: “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.”

But years later, after the conversations on race in America evolved on the internet and social media, and the phenomena of the case had been cross-examined in the Emmy winning series The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story and the Oscar-winning documentary O.J.: Made in America – and memorialized by rap mogul Jay-Z’s classic The Story of OJ – the line that ultimately resonates allegedly comes from The Juice himself: “I’m not Black; I’m O.J.”

The distance O.J. Simpson so often put between himself and the Black community was key to his appeal before the murders. Here was an affable football star – you could go as far as calling him servile – who wouldn’t raise a fist or take a knee (like the Black athletes that came before or after him). He didn’t pose a threat to white supremacy as Muhammed Ali or Jim Brown did when speaking up for Black rights before him. As civil rights activist Harry Edwards recalled in O.J.: Made in America – a riveting must–see documentary exploring every angle of his legacy – the football star uttered his “I’m not Black” refrain when refusing to join the 1968 Olympic boycott.

Instead, Simpson cozied up to the country-club crowd and was instantly rewarded with brand deals. He was the guy in those Hertz rental car commercials. He also peddled Chevys, fried chicken and orange juice (how could he not?!). He had an acting career, appearing in Dragnet, The Towering Inferno and The Naked Gun movies, where his presence was not unlike that of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson; not a good actor but welcomed as a self-deprecating presence eager to be liked.

That whole legacy as a hall-of-fame athlete and movie star, however, was eclipsed by the murders and subsequent media circus, which changed the way we consumed news, celebrity and entertainment forever.

Ninety million viewers worldwide tuned into watch Simpson’s curious white Bronco chase live, with Larry King providing commentary on CNN, riveted by the news chopper footage capturing the two-hour pursuit through Los Angeles. Some even joined in, lining the highways and streets to show support while LAPD patrol cars followed the SUV along the freeways at low speeds, following Simpson to his Brentwood home while he repeatedly threatened to shoot himself.

That this scene played out while bomb-on-a-bus thriller Speed was in theatres was one of those uncanny coincidences. Speed stars Keanu Reeves as an LAPD officer who pursues the bus in a Bronco, boards it and navigates the vehicle under police escort along L.A. freeways while news choppers feed the footage to a captivated audience. At one point the villain, played by Dennis Hopper, remotely detonates a part of the bomb, watching the explosion live on the news. “Interactive TV,” he cheers, prophetically. “Wave of the future!”

The viewership behind that white Bronco chase was motivation for networks like Fox and NBC to cough up their own 24-hour news channels so audiences could consume sensational stories like this uninterrupted. Perhaps such networks were already on the way and the Simpson saga arrived in time to provide justification for round-the-clock coverage that social media provides today. Court TV, for instance, was already in place. But now it could build its following on a blockbuster trial with incredibly high stakes and a mass audience hoping the cameras would keep the justice system honest.

Courtroom Drama

The Simpson trial was the real-life sequel of sorts to the Rodney King video and the subsequent L.A. riots. The sensational courtroom drama became less about whether O.J. Simpson, a known abuser, had finally murdered the woman he had violently tormented for years, and more about whether the justice system was once again abusing their powers to punish someone from the Black community. That’s right, the Black community, which Simpson had never claimed to be a part of until this trial, when his skin colour became his only plausible defence against the DNA evidence that left a trail from the murder scene to his bedroom.

To dress him up as Black, Simpson’s defence team, led by Johnnie Cochran, swapped out all the photographs on the wall leading to his bedroom. The old photos showed him hanging with all his Caucasian friends. According to Carl E. Douglas, another civil rights lawyer on the team, they replaced those pictures with photographs of Simpson with his Black family members. They also threw in a Norman Rockwell lithograph – The Problem We All Live With, the legendary Civil Rights era work featuring the image of six-year-old African-American child Ruby Bridges being escorted by law enforcement to attend a desegregated New Orleans school – so that the mostly Black jury would be convinced that Simpson was one of them, down with the cause.

They also went to work putting the LAPD on trial, which the entire justice system – and on-scene detective Mark Fuhrman’s own racist history – made rather easy. And they used all the cameras to their advantage, wielding the theatricality of it all to play not just to the jury but also the court of public opinion.

Think about all the bombshell ’90s-procedural-worthy moments: a Hollywood screenwriter on the witness stand with recordings of Mark Fuhrman saying the n-word – leading CNN to literally coin the term “the n-word” for their reporters to explain what was happening live on air; Simpson, a movie star, mugging for all the cameras when trying on a glove left at the murder scene; Cochran, an explosive orator, rhyming “fit” with “acquit.”

“This case is a circus,” lamented prosecutor Christopher Darden. He wasn’t wrong. It was also our first real taste of reality TV.

TV Gets Real

The reality TV genre was born with The Real World in 1992, but O.J. Simpson was the first reality TV sensation (the supporting cast at his trial also gained their own degrees of notoriety). Detective Fuhrman became a forensic and crime scene expert for Fox News Channel. Lead prosecutor Marcia Clark became an author and television personality, working as a special correspondent for Entertainment Tonight, of all places. District attorney Gil Garcetti became the consulting producer on legal dramas All Rise, The Closer and Major Crimes. TMZ founder Harvey Levin, who took feeding our craven appetite for catching celebrities in the wild to the next level, was a reporter in the courtroom. The O.J. trial was his transition from covering law to celebrities.

And then, of course, we all first heard the name Kardashian during the Simpson saga. Simpson claims to be Kim Kardashian’s godfather. Her father, Robert Kardashian, was sitting on Simpson’s defence team, while her mother, Kris Jenner, was sitting in the courtroom on the side of her best friend Nicole Brown. We truly went from chasing O.J.’s white Bronco to Keeping Up With The Kardashians.

The Simpson trial was the petri dish out of which much of our current pop culture landscape grew. The way we consumed the Johnny Depp/Amber Heard trial on social media, and searched for every hot take about it afterwards to reinforce our own beliefs, was practiced with Simpson and the 24-hour news cycles. The way we all became litigators online, exonerating and crucifying celebrities for their every caught-on camera digression or bad tweet, is just an echo of the headlines and dining room conversations of the ’90s. The Simpson case even whet our current appetite for true crime shows like Don’t F— With Cats and Dahmer. American Crime Story and Made in America were both early entries in the new wave of content exercising our forensic evidence expertise.

These shows also gave us the opportunity to re-litigate the case, as well as the verdict. Simpson, who eventually served time for a robbery case, went free in what many believe was a response not to the evidence but police brutality and unfair justice system practices victimizing the Black community.

(He subsequently lost a 1997 civil trial that found him liable for both deaths, and awarded the victims’ families $33.5 million. He was also sentenced to 33 years in prison for his part in a 2007 armed robbery case in which he and accomplices stole Simpson memorabilia from a dealer in Las Vegas. Some viewed the exceptionally long sentence as a form of revenge for the failure to convict him in his murder trial. Simpson served almost nine years before being released on parole.)

Today, Simpson might not be so lucky. The culture has evolved. We know the history of false claims made against Black men accused of perpetrating violence against white women. We know that history has led to lynchings. We also recognize the patterns of serial abusers that can lead to murder. These conversations have become more nuanced, less polarizing and made for a public that can embrace multiple truths.

Just look at the response to Black actor Jonathan Majors, who was immediately dropped from his roles in Marvel movies and more after his conviction for assaulting his white girlfriend Grace Jabbari. There’s little outrage over that verdict, perhaps because of Simpson.

This is, after all, O.J.’s world. He may be gone, but we’re still living in it.

RELATED:

O.J. Simpson, Football Star Turned Murder Defendant in “Trial of the Century,” Dead at 76