Beyond Reykjavik: Discovering the Warmth of Icelandic Community Spirit on a Tour of the Arctic Circle

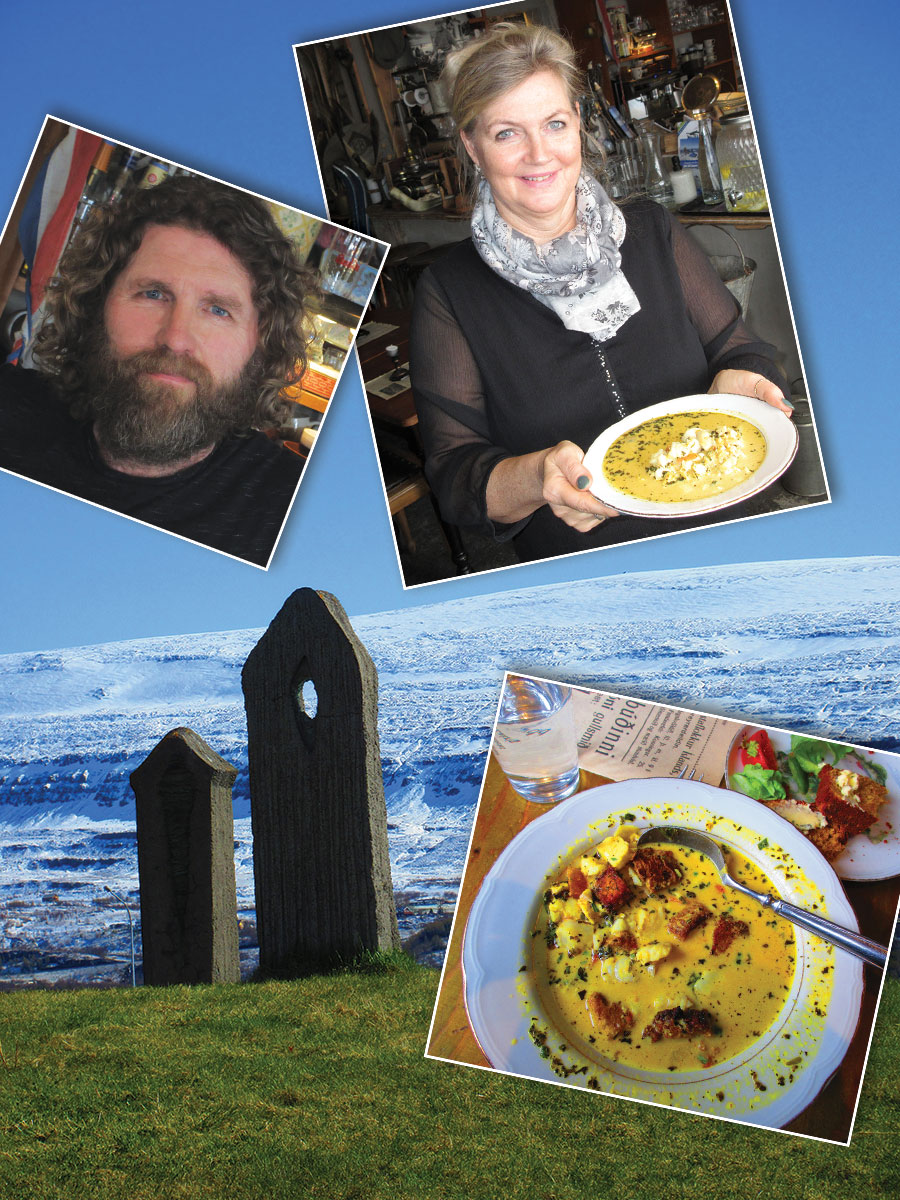

Grimsey Island, Iceland’s northernmost point. Photo: Courtesy of Iceland Tourism; Inset: Icelandic lamb meat. Photo: Audunn Ljosmyndari

“Tah!” I cried to the lady who ran the guest house. “I’m off to conquer the Arctic Circle!”

“Have fun,” she said, barely looking up.

Normally, Arctic explorers are sent on their way with tickertape parades, teary-eyed sweethearts, jubilant crowds and dockside oompah bands, but no worries. I was off! Forty-six minutes later, I had arrived, aided by a sign with an arrow that read, essentially, “Arctic Circle, that-a-way,” which did make things easier, I admit. (Those explorers of lore would have been greatly assisted by proper signage.)

On a windswept slope, a large concrete sphere marked the dividing line between darkness and light. On the other side of that sphere lay six months of darkness every winter, six months of daylight every summer. Grimsey Island is the only place in Iceland that straddles this divide, beyond which lies the wheel and cry of seabirds, the heave and fall of the sea, and – eventually – Greenland.

A blustery day. Eyes watering from the wind, I might have stayed and contemplated the personal and geographic boundaries of life. But my stomach was growling and the promise of food beckoned. Before I get to that, though, let me go back to the beginning…

Dalvik

Iceland’s north, far beyond the capital of Reykjavik, is a land of dramatic mountains and equally dramatic coastlines, of cosy villages – and soup. Icelandic soup. A savoury category all its own.

I’d been invited to speak at the Iceland Writers Retreat – a series of workshops and cultural tours co-founded by Canadian-born Eliza Reid, who is married to Icelandic President Guðni Thorlacius Jóhannesson – where I was asked to impart my authorial wisdom to others. Fortunately, not having a lot of wisdom to impart, I was wrapped up in a few days, which freed me for a journey farther north, to the end of Iceland itself.

I flew to Akureyri, Iceland’s lively “second city,” and then took a bus an hour, along the deep cleft of the Eyja fjord to the harbour at Dalvik.

This was where the ferry to Grimsey departs, but I’d heard rumours of soup – fish soup, in particular, a local specialty as featured at a restaurant in Dalvik with the daunting name Gisli, Eirikur, Helgi – Kaffihús Bakkabræðra. Luckily, its soup is famous enough that I had only to ask passersby, “Fish soup café?” and I was gently steered to the right location. “Já, beside the theatre.” I entered a pleasantly dishevelled establishment, rife with knickknacks and bric-a-brac, and was greeted by the irrepressible Kristin Adalheidur Heida, proprietor of said establishment. “My own recipe,” she said as she ladled out a bowl. Fresh cod, coconut milk and root vegetables were the only items I could discern with any confidence. The rest was off-limits, no matter how much I pleaded or cajoled.

“She won’t even tell me what’s in the soup!” said her husband Bjarni Gunnarsson, a full-bearded Viking from across the bay. “So I don’t think she’ll tell you.” It was hearty, with firm-fleshed fish and layers of flavour. Even better, it came with a side of “beer bread,” a speciality of Kristin’s.

The nearby Kaldi Brewery provided her with the yeasty mix, depending on what they are brewing that day. “Sometimes dark ale, sometimes blond, sometimes an IPA. So the taste changes, and the bread can be black, red, yellow.” Dense and tangy, it went perfectly with the soup.

Even better, it led me to Kaldi Brewery’s spa where one can – quite literally – bathe in beer. If one were so inclined. Spoiler: I was.

The Beer Spa

After the fish soup in Dalvik, I made my way to the nearby fishing village of Árskógssandur, pop. 119, which is home to Iceland’s first – and most celebrated – microbrewery. “My dad was a fisherman; my mom was the store manager,” said Siggi Olafsson, head brewmaster at Kaldi. “But then my dad got injured and couldn’t work. One night, my mom was watching a show on Danish breweries and she had her light-bulb moment. ‘We have the best water in the world right here!’ she said. ‘Let’s open a microbrewery!’ So we did.” The rest is history.

“Your mom sounds like a force of nature,” I suggest.

He laughs. “Oh, she is.”

Olafsson was sent to study the beery arts of the Czech Republic, returning to become Iceland’s youngest brewmaster at age 19. “We started with a Pilsner-style beer,” he said. “Unpasteurized, without preservatives or added sugar.”

Today, they have a full line of award-winning beers, from a spiced pale ale to their flagship blond, from an English-style brew to a Christmas porter with chocolate added. The brewery was a success. “Then mom decided we should add a spa. And a restaurant.” The restaurant is proudly local, sourcing its ingredients directly from the town. “We’re part of the community,” Olafsson said over a dinner of lamb and roasted vegetables. “And the community is part of us.”

In the adjoining spa, guests soak in wooden tubs filled with young beer, brewer’s yeast and hops. The result is a very creamy bath. With a rich aroma. More like caramel than beer. (The yeast in particular is steeped in B vitamins. Wonderful for skin and hair, I’m told.) The rooms are private and soothingly lit, with beer on tap right next to the bath, so one can fill a mug as often as one likes. “It’s romantic, as well,” Siggi assures me. “Couples come all the time, share a bath.” A spa – with limitless beer? Sounds like a win-win for most couples.

After my bath – alone, alas – I moved to the hot-spring tubs outside, which look out over the full sweep of the fjord. Sometimes, whales can be seen breaking the surface of the water. Iceland beyond Reykjavik is a world of its own.

Grimsey Island

Thus warmed with a beer bath and fish soup, I was ready to face the North Atlantic. A three-hour ferry ride takes travellers across, rising and falling, rising and falling. (If one is easily queasy, there are flights to Grimsey.) The Arctic coastline has massive, muscular mountains that plunge directly into the sea, while the low flat rise of Iceland’s farthest outpost draws nearer.

Seventy people make their home on Grimsey. A working fishing port, it is an island enshrouded in seabirds: kittiwakes and razorbills, fulmars and the always-popular puffins, who have burrowed nests in the grassy hillocks right in town, across from the community centre. In Iceland, puffins are nicknamed “the pastor” for their slightly serious, slightly pompous air. And they do blend dignity and comedy, especially in flight.

After my (heroic) trek to the Arctic Circle, I stopped in to speak with Halla Ingólfsdóttir of Arctic Trip tours, who first came to Grimsey 23 years ago to visit a sister who had married a local man. I had been told she was the person to ask about anything Grimsey-related. Ingólfsdóttir fell in love with Grimsey and has been returning ever since. For the last eight years, she has more or less lived here. When I asked why the island has such a hold on her, she said, “I could spend all day telling you.”

It was the rhythm of life on the island that appealed to her, more than anything. “You are out here in the middle of the North Atlantic, never knowing what the weather will be tomorrow or the next day. It forces you to live in the present. And to rely on others.”

She was preparing lamb soup for a community get-together that very evening. Regional elections were underway and representatives from the Pirate Party – which runs on a community-based, anti-corruption platform – were hosting a town meeting to discuss local concerns.

As one might expect, candidates for a party called “Pirates,” were not your usual political players. Far from ruthless buccaneers, they were a pair of very vivacious, very funny women named Hrafndís Bára and Erna Sigrún. They invited me along to the meeting.

It was, of course, held entirely in Icelandic. No prob. I just frowned whenever everyone else frowned, nodded in agreement when the others did, chuckled wryly and shook my head when they did likewise. And my reward was soup! Succulent Icelandic soup. At the meeting, I met Ingólfsdóttir’s nephew, Ingolfur, and his young son, a cherub-like toddler named Svafar – with an eight-year-old cousin attending school in Akureyri, he’s the only child on Grimsey. As might be expected, Svafar is a star. His joyful arrival was treated like that of a celebrity’s, and no wonder. The entire community doted on the little guy. “My son’s name is from ancient Norse,” said Ingolfur, whose father and grandfather before him were fishermen too. “It’s a Viking name.”

I asked him about fishing the North Atlantic, expecting sage Norse wisdom about “reading the wind.” Instead, he pulled out his smartphone and showed me the sonar channels they use to track their catch. Viking names and the latest smartphones. In a word: Iceland.

I was heading back to Akureyri the next day, and Bára of the Pirate Party invited me to dinner at her place, when I got there. And she would prove true to her word. “I’ll make you real Icelandic food,” she said. It would be traditional fare, including a reindeer she had personally shot. She showed me a picture of herself, smiling, hunting rifle in hand, next to the animal I would later be served. It’s rare to be pre-acquainted with one’s dinner, but I heartily agreed.

“We’ll have the reindeer with rhubarb jam, plus grafnar gæsabringur (cured goose breast) and hangikjöt (dung-smoked mutton) with súr lifrarpylsa (sheep-liver haggis) and súrar lappir (don’t ask).”

“Sounds good,” I said. “I’ll bring the beer.”

Literary Iceland

Iceland’s first lady, Eliza Reid, is Canadian, and a writer as well. She’s the author of Secrets of the Sprakkar, which honours Iceland’s remarkable women. She’s also the co-founder, with publishing consultant Erica Green, of the Iceland Writers Retreat. Reid believes “a country’s literature gives us a glimpse into its soul.” Green agrees, noting that Iceland is very much a book reader’s paradise, boasting more readers – and more writers – per capita than any other nation. Reykjavik has been designated a UNESCO City of Literature. The best way to appreciate this? Green suggests something as simple as “reading a good book in one of Reykjavik’s coffee shops.” Iceland Writers Retreat (registration is now open), April 26 – 30, 2023; icelandwritersretreat.com

You can also visit the historic homes of Iceland’s greatest authors; below are a list of my favourites.

Laxness House: Halldór Laxness won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955, and his home, a sun-filled, book-lined refuge, is just outside of Reykjavik. Laxness is readily available in English and, outside the murderous noirs of Yrsa Sigurðardóttir, his novel Independent People was the one most recommended to me by Icelanders. (The Iceland Noir Literature Festival, meanwhile, takes place Nov. 16 – 19, 2022; icelandnoir.weebly.com

Sigurhæðir: Below the church in Akureyri’s Old Town is the beautifully situated childhood home of poet Matthias Jochumsson. Set on a hill, it has a step-waterfall in front. Jochumsson also penned Iceland’s national anthem, “Lofsöngur,” in 1874, which contains such aptly poetic lines as “eternity’s lone small flower with trembling tears.”

Nonnahús: On the same street sits the home of Iceland’s beloved children’s author, Jon “Nonni” Sveinsson, who has been translated into 40 languages and remains popular in much of Europe, especially in Germany. Built in 1850, his home has been faithfully restored and looks out across a park to the mountains on the other side of the fjord.

If You Go:

For north Iceland, including Grimsey and Akureyri, visit: northiceland.is/en

Kaldi beer spa: bjorbodin.is/eng

Arctic Trip tours on Grimsey: arctictrip.is

And for more about Iceland’s raucous Pirate Party: piratar.is/xp/frettir/english-news

A version this article appeared in the August/September 2022 issue with the headline ‘Beyond Reykjavik’, p. 78.

RELATED:

Travel 2023: Ways to Save Money and Live a Life of Bleisure

Workcations: Digital Nomad Visas Offer the Best of Two Worlds