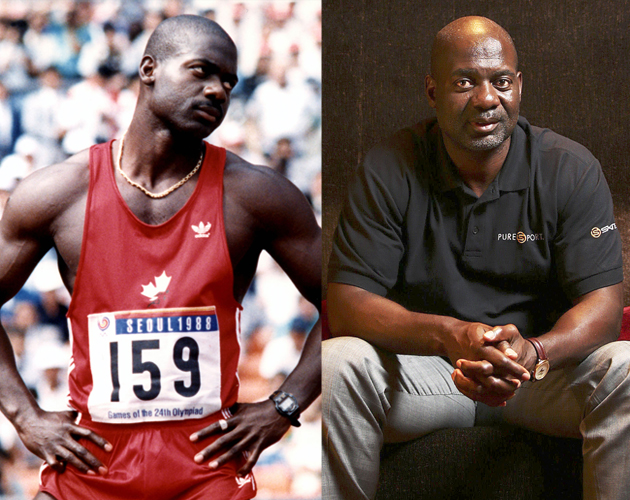

Ben Johnson: Where Is He Now?

We look back at one of the biggest Olympic scandals involving a Canadian athlete and find out what Ben Johnson is up to now.

The world was watching as Usain Bolt’s finished his 100 metre sprint on Sunday in 9.81 seconds—adding more gold to the pile he already has.

Boomers will likely recall watching the 100 metre race in the 1988 Olympics in Seoul—often described as “the dirtiest race in history.”

That was the year when Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson smashed the world record for the 100 metre and won his gold medal, easily beating his biggest rival, American Carl Lewis.

In 9.79 seconds, he put on what CNN has described as “a display of power and awe never before seen in track and field, against the greatest field of sprinters ever collected.”

He told reporters, “”I’d like to say my name is Benjamin Sinclair Johnson Jr, and this world record will last 50 years, maybe 100.” Later he said: “A gold medal—that’s something no one can take away from you.”

Within days, he was ignominiously stripped of his medal after drug tests showed traces of the banned steroid stanozolol in his urine.

Canadians were horrified to find out that they’d been represented by a cheat, and that someone they’d celebrated as a Canadian hero was seen by the world as a fraud.

He’d already been invested in 1987 as a Member of the Order of Canada: “World record holder for the indoor 60-metre run, this Ontarian has proved himself to be the world’s fastest human being and has broken Canadian, Commonwealth and World Cup 100-metre records.”

A year after the Olympics, at the Canadian government’s Dubin Inquiry, Johnson admitted that he had lied. His coach told the inquiry that Johnson had been using steroids since 1981. Johnson was born in Jamaica in 1961. He was 15 when he came to Toronto with his mother. He linked up with trainer Charlie Francis who started him on steroids because, it’s been reported, he believed everybody was doing it and getting away with it.

In fact, nearly everybody was doing it and getting away with it—and drugging, at least for the Russians, kept happening right through the 2014 winter Olympics in Sochi, and even into the current Summer Games.

At the time of the Ben Johnson scandal, no less than six of the eight finalists in that 100 metre race would eventually be implicated in doping scandals, including Lewis, who it was later revealed had tested positive for stimulants at the US Olympic trials, according to the Telegraph.

In an interview with a Telegraph reporter in 2013, Johnson admitted to years of steroid use, but still feels he was unfairly picked out for vilification at a time of widespread drug use in athletics. “I was nailed on a cross, and 25 years later I’m still being punished,” he said. “I know what I did was wrong. Rules are rules. But the rules should be the same for all. But politics always plays in sports.”

Asked what he would change if he could go back 25 years, Johnson said there was no point trying to live in the past. “But I still believe I could have won the Olympic Games without any drugs back then,” he added.

Johnson was in London in 2013 to promote the World Anti-Doping Agency, a global athlete’s association. He said he got involved because his granddaughter started asking questions about his past and showed interest in track-and-field sports. “I don’t want her entering a world of drugs,” he told the Daily Mail.

It was this venture that provided some redemption.

Some of his past ventures, however, was ridiculed.

He went to Libya to work for the family of Muammar Gaddafi, coaching the dictator’s third son, Al-Saadi, in his effort to play professional football. During his three-year relationship with the family he saw, first-hand the horrors of the Gaddafi regime.

In Japan, where he became something of a cult figure, he earned money participating in such stunts as racing against turtles or getting fitted with a weights belt and running along the bottom of a pool in a contest against a Japanese swimmer.

He coached his buddy Diego Maradona for a short time in Toronto, when the soccer star’s career was waning.

In 1998, he raced against a thoroughbred race horse, a harness racing horse and a stock car in a charity race in Prince Edward Island. He finished third.

In 2006, he appeared in TV commercials for an energy drink called Cheeta Power. One ad featured the CEO of the drink manufacturer asking Johnson, “Ben, when you run, do you Cheetah?”

“Absolutely,” says Johnson. “I Cheetah all the time.”

And in what may have been his greatest folly—after cheating in the Olympics, of course—he allowed himself to be convinced by faith healer, Bryan Farnum, that he was a reincarnated pharoah and that Carl Lewis was a reincarnated enemy from thousands of years ago.

All that and more is in the autobiography—the Daily Mail called it “mumbo-jumbo”—that Farnum co-authored, titled From Seoul to Soul.

Now 54 years old, Johnson has pretty much avoided publicity and scrutiny in the last few years.

Last summer, TSN reported that he was working as a trainer with pro athletes, including Florida Panthers forward Anthony Stewart and Nashville Predators defenceman P.K. Subban.

“We started working together three times a week, but we’ve gone down to two a week,” Johnson told TSN. “I don’t want to overload his [Subban’s] muscles. He’s doing strength and acceleration and some agility. He’s going to be even better, even faster next year.”

Inevitably, during these Olympic Games, there will be a debate among people who remember Ben Johnson’s race and who watch Usain Bolt.

With today’s training methods and technology—and without drugs—who would win gold?