Face Value: How Photo Filters and Cosmetic Enhancements Are Distorting Our Perception of Aging

The proliferation of photo filters and cosmetic enhancements on social media may be distorting our perception of beauty and aging. Photo: Plume Creative/Getty Images

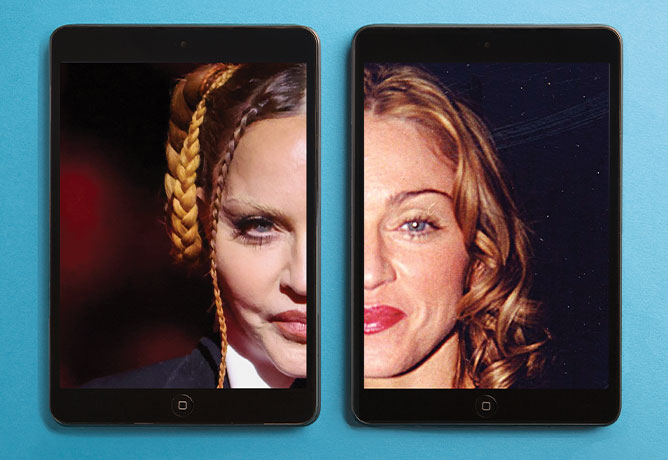

When Madonna took the stage at the 2023 Grammy Awards in February to introduce the icon-smashing hit song “Unholy,” the shocker — she is Madonna — wasn’t what she wore or what she said, it was her radically altered face. For millions of fans viewing the spectacle of her metamorphosis on the live broadcast, it was a double shocker, since no social-media filtering was involved. Her face was her face.

Living as we do now at the nexus of cosmetic alchemy and the filtered image, perception versus reality is a winless proposition. Sales of plastic surgery and cosmetic procedures reportedly shot up as the pandemic receded. On social media, beauty filters are commonly used by public figures and average Joes. In the era of the photo-editing app Facetune, the number of boomer-aged celebrities on Instagram who look exceptionally, remarkably and sometimes frighteningly youthful is growing.

Madonna’s face bears little resemblance to the original Material Girl’s. At 64, it’s rounded, smoothed, glossed and, quite literally, filled. Fashion designer Vera Wang, 73, appears preternaturally sylph-like with the smooth skin of a tween, her long black hair framing her face Yoko Ono-style. Actor Salma Hayek, 56, with her wasp waist and prodigious bosom, seems to have the complexion of an eight-year-old. At 77, actor Jaclyn Smith, best known as one of Charlie’s Angels — a TV show that aired from 1976 to 1981 — looks radiant, glowing and the same (just a whole lot more sculpted). And Joan Collins, a.k.a. Alexis Carrington of Dynasty fame, who will turn 90 in May, is a woman with extremely good genes, it seems.

Whether it’s filtering or surgery, you don’t know what anyone really looks like anymore, apart from Jamie Lee Curtis, 64. It’s not encouraging that it’s been 20 years since the American actor posed, unretouched, and with no makeup, for More magazine in a sports bra and underwear — her personal bid to bust the perfection myth. And it’s been six years since Allure Magazine banned the term “anti-aging” from its pages. What makes this social trend even more confusing is timing. Just as filtered images dominate social media, the fashion and beauty industries are attempting to become more inclusive, authentic and body positive.

Paulina Porizkova, 57, the former supermodel-turned-author (her book, No Filter, was released last November), has become an anti-ageism guru on Instagram. “Embrace your age” was the message when Harper’s Bazaar put 76-year-old rock star Patti Smith on its cover — lined face, long tangled grey hair and all. And in January, the CEO of Coty, the global cosmetic consortium, sent an open letter to the world’s major dictionary publishers exhorting them to “un-define” beauty, calling the current entries “limiting and exclusive.”

Still, the world’s got a long way to go. While a deeply wrinkled Mick Jagger, 79, is perceived as a rock ’n’ roll rebel to the end, Smith aging “naturally” seems like a heretical act. It’s no surprise, since our perceptions have been manipulated for as long as mass media have existed. All our lives, we’re fed a steady diet of unrealistic images convincing us how we should look. In the ’90s, the glamazon supermodels reigned supreme, until a bone-thin, teenaged Kate Moss hit the runway, tipping fashion towards the waif look and setting body image standards that were aspirational in all the wrong ways. As a trend – dubbed “heroin chic” — it had seismic social implications, blamed for encouraging anorexia, distorting reality and promoting self-harm. Even then U.S. president Bill Clinton denounced it. Today, social media has exponentially intensified the impact of unrealistic images. Filtering has upped the ante.

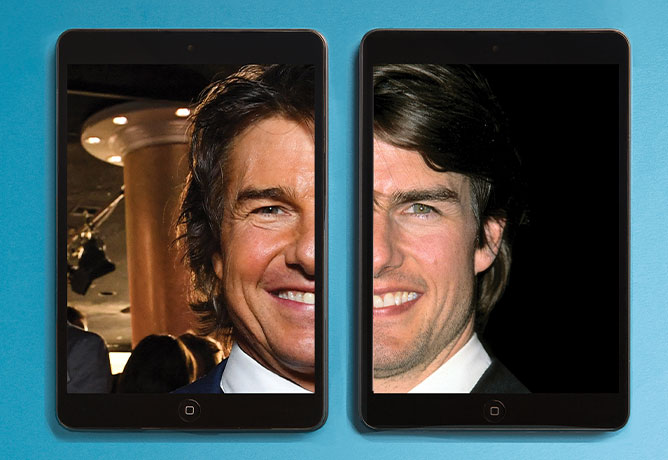

In Hollywood, where an actor’s face is their brand, filters are occupational tools and considered standard entertainment industry practice, but it goes beyond the Instagram feed. When Tom Cruise reprised his role in Top Gun: Maverick 36 years after the original, the internet buzzed with praise and speculation about his ageless looks. Dermatology pundits and gossip sites weighed in, as did Men’s Health magazine (“How Tom Cruise Maintains His Youthful Looks at 59 and You Can Too”). Top tips included paying special attention to diet, mindset and athletic training. Notably absent were mentions of Botox, “nip and tuck” or visual effects.

On a recent episode of The Town with Matthew Belloni, an inside Hollywood podcast, the host discussed how stars are de-aged with computer software. Hollywood’s open secret for years, it’s a practice that’s become more prevalent thanks to AI-enabled technology. Although consumers are largely unaware of the process, Belloni’s guest, VFX expert Matt Panousis — co-founder of a Toronto company that uses software called Vanity AI — estimated stars are digitally enhanced on screen in 85 per cent of movies. Some actors require a de-aging budget allocation written into their contract before they’ll sign.

Today’s most popular social media platforms, such as Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok, developed so quickly that significant research examining their impact is scant. As an overview, a Statistics Canada survey released in 2021 reports one-fifth of all Canadian social media users aged 15 to 64 had lost sleep, been less physically active or had trouble concentrating as a result of doomscrolling. In more recent smaller studies and media reports, the focus is predominantly on young women, for whom filtered images are a constant and consuming reality, one that can have troubling mental health consequences from low self-esteem to depression. Even Instagram’s internal research found that, among teen girls who reported dissatisfaction with their bodies in the previous 30 days, about 30 per cent said Instagram made it worse.

In an article originally published in the journal JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, Boston University associate professor of dermatology Dr. Neelam Vashi and her colleagues concluded that filters are at odds with reality. “People can take a photo of themselves and, in an instant, manipulate it,” Vashi said in a psychologytoday.com story on what’s been dubbed Snapchat dysmorphia. “That makes a change feel more real and attainable. It can be argued that these apps are making us lose touch with reality because we expect to look perfectly primped and filtered in real life.”

Much has been made in the media of “Instagram face,” referring to a singular look that has proliferated among young women, the result of filtering and/or plastic surgery. In Jia Tolentino’s words in The New Yorker: “It’s a young face, of course, with pore-less skin and plump, high cheekbones. It has catlike eyes and long, cartoonish lashes; it has a small, neat nose and full, lush lips. It looks at you coyly but blankly, as if its owner has taken half a Klonopin and is considering asking you for a private-jet ride to Coachella. The face is distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic — it suggests a National Geographic composite illustrating what Americans will look like in 2050, if every American of the future were to be a direct descendant of Kim Kardashian West, Bella Hadid, Emily Ratajkowski and Kendall Jenner (who looks exactly like Emily Ratajkowski).”

Instagram face is largely a phenomenon of the millennial generation, of course. But if the assumption is people in mid-life should know better than to fall prey to the dark allure of social media, then think again. Just as it can be useful for disseminating information, social media can also spark envy, warp standards and trigger anxiety. “The pressure is extreme,” Toronto dermatologist Dr. Sandy Skotnicki says in a telephone interview. In her practice, patients’ requests are often unrealistic and she finds herself “saying ‘No’ more than ‘Yes’.” Skotnicki believes her job is to preserve the “golden ratio,” a long-established mathematical formula used to measure the human face for optimal perceived beauty.

For a reality check, the internet is a dark hole of before-and-after cosmetic alteration shots, but it’s the “afters” that become the images of record. Fashion designer Marc Jacobs, 59, defied the status quo when he posted a picture of his bruised face swathed in bandages the day after a deep plane facelift. He told Vogue: “In a world where a younger generation is all about transparency, disclosure, and honesty, I don’t see why people have this shame around vanity or keeping up with a certain thing. You know, we all retouch and filter our pictures. That’s the world we live in.”

And yet, we buy in. We know not every image represents reality and #nofilter is merely rhetorical, so why not take it for what it is — a bit of fantasy and fun? Well, just try it yourself. Download the Facetune app and retouch your image, filter yourself back in time, and you’ll quickly understand the power of artifice. When it comes to our self-perception, it seems we’re fragile creatures and prone to delusion, too.

“People forget what they looked like a week after they’ve had a procedure,” says Dr. Trevor Born, a cosmetic surgeon with practices in Toronto and Manhattan. “And after a year, they can’t believe they ever had a heavy neck or bad skin. It’s astounding.” This is called “perception drift,” a term coined by Dr. Sabrina Fabi, a dermatologist in San Diego, Calif. It’s when a person’s perception is skewed after having a series of cosmetic procedures, and they’re “unable to accurately process their appearance.”

So, possibly Madonna drifted. Or perhaps she’s fully aware of how she looks, and likes it. Either way, the provocateur par excellence has sparked a conversation about agency and ageism, technology and society’s taboos. “I have never apologized for any of the creative choices I have made nor the way that I look or dress and I’m not going to start,” Madonna posted on Instagram in response to her critics following her Grammys appearance. “A brilliant provocation” is how Madonna’s new face was characterized in the New York Times. And in The Guardian, journalist Nancy Jo Sales wrote: “Whatever Madonna’s being criticized for, that’s what she’s asking us to examine.” Sales’ view is that Madonna’s latest subject as an artist is ageism. If so, then she’s vividly demonstrated our society’s intolerance of aging across the board — and especially unfiltered.

A version this article appeared in the April/May 2023 issue with the headline ‘Face Value’, p. 54.