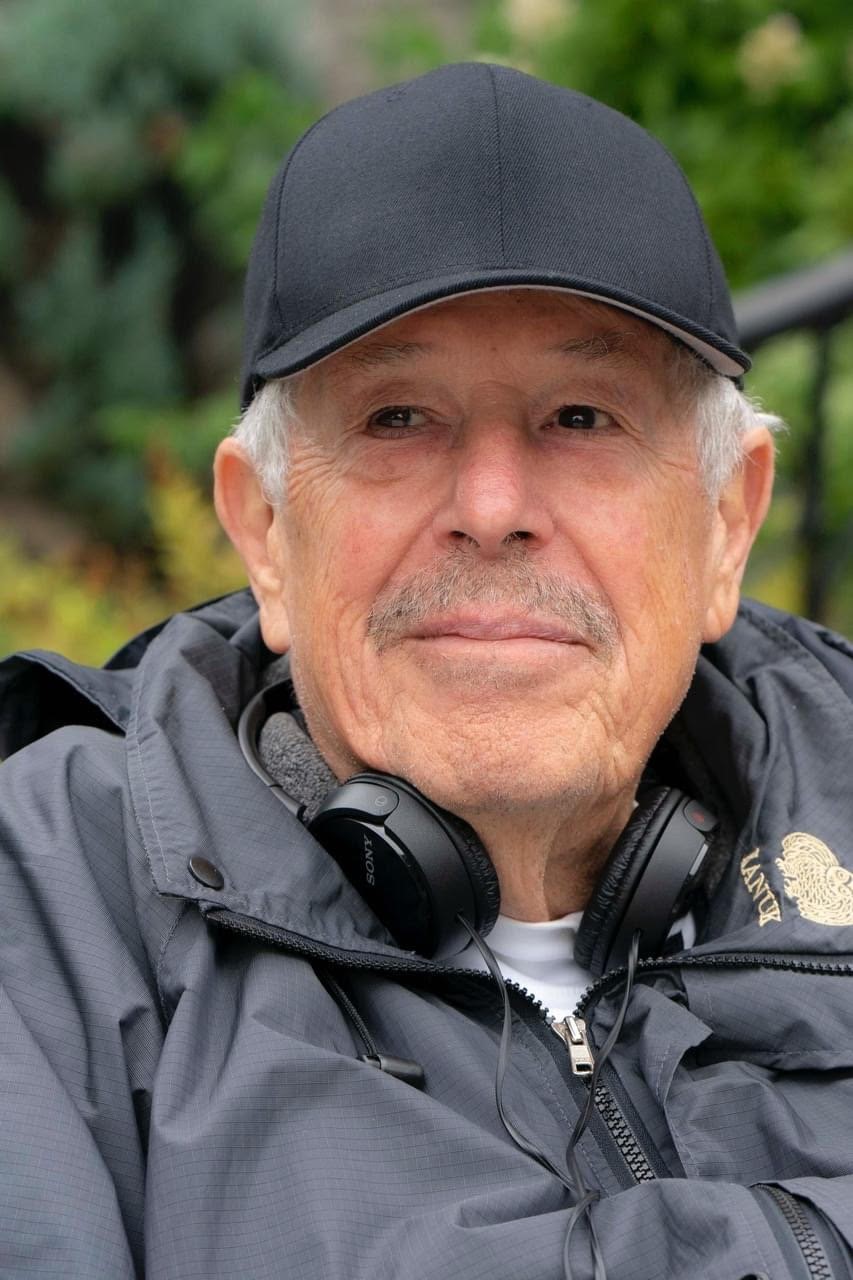

Quebec Auteur Denys Arcand Talks ‘Testament’ — Likely His Final Film — and Why His “Cynicism Is Melting Away”

Quebecois singer Marie-Mai and star Rémy Girard in 'Testament' — the latest film from legendary Canadian director Denys Arcand. Photo: TVA Films

Denys Arcand has a thing for history. It’s evident from just a glance at the titles of his most celebrated films — his Oscar-nominated sex comedy, The Decline of the American Empire (1986) and its Oscar-winning sequel, The Barbarian Invasions (2003). But Quebec’s veteran writer-director has tended to use history as a backdrop, with the death of Western civilization lending context and gravitas to witty contemporary satires targeting his own world of left-wing intellectuals. Barbarian Invasions, after all, was not about the end of history, but the end of a philandering history professor whose final indulgence is staging a farewell party around his heroin-induced euthanasia.

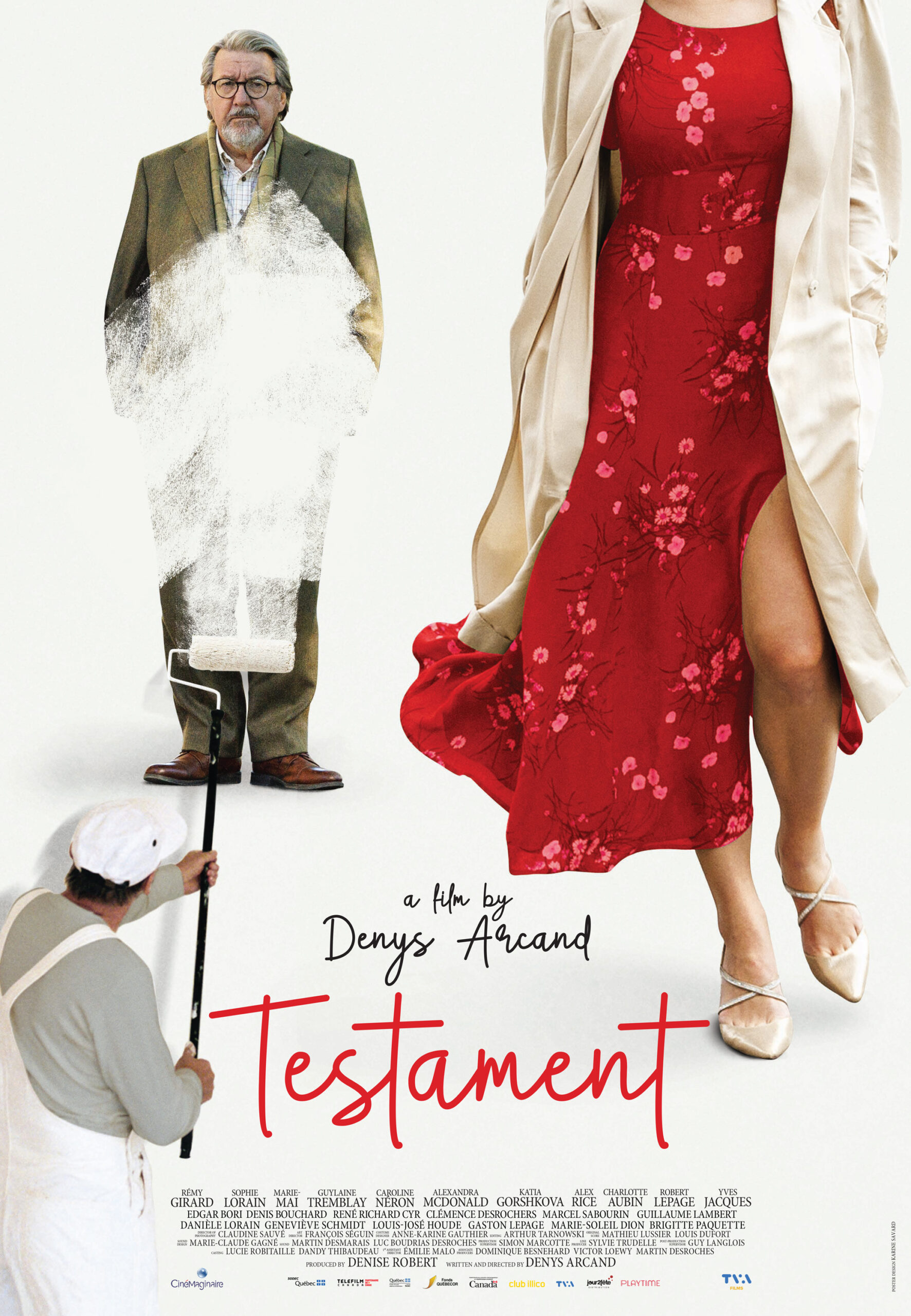

At 82, Arcand appears be putting his own career to rest with Testament, his latest film — and most likely his last. If so, it would be a worthy capstone for this beloved eminence grise of Quebec cinema. Now playing in theatres across English Canada, Testament proved a big success in Quebec, earning more than $1.5 million at the box office. And it brings Arcand’s bittersweet romance with history full circle with his signature cocktail of spritely satire and sage reflections on mortality. But for once, history is not a backdrop. It’s at the front and centre of the story, which concerns a protest over a 19th-century fresco on the wall of a retirement home that depicts Iroquois leaders welcoming Jacques Cartier to the New World.

Observing the controversy with bemused detachment is Jean-Michel, a retired archivist living at the home. A lifelong bachelor who likes strolling through cemeteries, he looks forward to a discreet death, mourned by no one, after an uneventful life at the National Archives, where he still works two days a week. Portrayed by Rémy Girard, the historian in Decline and Invasions, he serves as the film’s droll protagonist and an alter ego for its director.

“It’s me, but it’s not me,” says Arcand. “It’s a transposition of myself. I’m not an archivist. And I’m not really retired. I should be, I guess.” While he doesn’t rule out making another movie, he concedes that the odds are against it given his age. “So … it’s just the end.”

Arcand speaks via Zoom from his office in Montreal. The last time we talked was in 2004, over breakfast at L’Express, the city’s legendary French bistro. Barbarian Invasions had just won the only Best Foreign Language Film Oscar ever awarded to a Quebec movie before or since. At the time, he shrugged off the honour. “It’s nice when it happens,” he said, “but in the grand scheme of things it doesn’t mean much to me. The only thing that will validate a work of art is time, and by the time it’s validated you’re dead.”

Two decades closer to death, Arcand still comports himself with the same thoughtful modesty and wry charm. But his mood is sunnier. As an artist who has spent his life training a lens on the culture, this philosopher-filmmaker came to realize that he can lose sight of his own impact on it. He recalls an incident years ago, when he was between projects: “I’m in the supermarket, carrying my little basket and a woman comes near me. She doesn’t even look at me, and she says: ‘We’re waiting.’ I said, ‘What?’ I thought she wanted me to move so she could access the grapefruits. She said, ‘We are waiting. You think about it.’ And she goes away.”

She was waiting for his next film.

“That kind testimony I get every second day,” says Arcand. “I’ve been experiencing that for the last 10, 15 years, and it’s fabulous — people talking to me on the street, supermarkets, saying ‘You can’t stop now, we need to see another one.’ When I was younger and heard an old singer say ‘My audience won’t let me stop,’ I was very cynical — yeah, he just wants to make another pot of money. This is terribly sentimental, but there is a genuine love that you feel. It’s coming from them to you and you feel responsible. You’ve got to act on it. My cynicism is melting away because of all that love.”

In Quebec, Arcand is not just a celebrity; he’s a cultural institution. Unlike his friend and compatriot Denis Villeneuve, who soared into high Hollywood orbit with blockbusters Blade Runner 2049 and Dune, he has remained firmly rooted in Quebec. For a time, he was courted by the American studios after the success of Jesus of Montreal (1989), his second Oscar-nominated film. And he turned down a US$1 million offer to direct Meg Ryan in Sleepless in Seattle because he wasn’t allowed to rewrite the script, which “didn’t have a one good scene” (this was before Nora Ephron stepped in to salvage it). Arcand never looked back. Thirty years later, the prospect that Testament, his 10th dramatic feature, could be his last waltz aroused avid interest from his community.

Led by Girard, its cast is stacked with Quebec national treasures — from veterans Marcel Sabourin, Yves Jacques and Guylaine Tremblay to actor-director Robert LePage and multi-platinum pop star Marie-Mai. The film turned into “a festival of friendship,” says Arcand. “It’s full of people who said, ‘I want to be in your last one, whatever you need.’ So you have all these people who are very well known and just come in for one short scene.”

The film is riddled with cameos and fizzy repartee, but at its heart is a restrained and sardonic Remy Girard, 73, starring in his seventh Arcand film. “He’s got the right rhythm,” says Arcand. “It’s funny. We never see each other. I never ate at his house. Every five years we meet on a set and I don’t have to say anything. He understands exactly what I’m doing. The sort of melody that I like to have for my dialogue is entirely natural for him.”

Testament unfolds as an equal opportunity satire that skewers everyone from jaded cultural bureaucrats to naïve gen-Z idealists. But as Arcand navigates the minefield of identity politics, he suspends the satire when it comes to portraying First Nations faces and voices. Girard’s character, like Arcand, once played lacrosse against Mohawks as a teen, and there’s a wistful scene of him watching young players at a rink in Kahnawake.

Meanwhile, Mohawk actress Alex Rice, cast as a visitor from Kahnawake, stands before the controversial painting of Jacques Cartier meeting the Iroquois and delivers a harrowing review. “Well, it is what it is,” she says, her voice trembling. “This is an image of a foretold genocide.” She then steps out to confront the protesters camped on the lawn of the retirement home, who are not Indigenous. They’re a band of neo-hippie Anglos beating drums and wearing feathers — a preposterous caricature of “Pretendians.”

But the painting and the film’s premise were inspired by a real protest — over a diorama in the basement of the New York Museum of Natural History that depicts a Dutch colonial governor meeting loin-clothed Lenape tribesmen in 17th-century Manhattan. The museum resolved the dispute in 2018 by planting 10 text panels on the diorama’s glass façade to correct clichés and inaccuracies in its portrayal of Native Americans. “The whole painting was corrected,” says Arcand. “And that got me thinking. Eventually we could ask for a correction of all Western art. The Sistine Chapel could have a glass front saying ‘God is presented as an older white man with a beard.’ Why not an African lady? Why not a Japanese teenager?”

The painting that covers a whole wall in the retirement home was created specifically for the film by Arcand’s art director, François Séguin. A painter who had worked with him to forge Renaissance masterpieces for Neil Jordan’s Showtime series, The Borgias, created a canvas in a period style that looks vividly authentic and downright gorgeous.

Arcand, famous for films brimming with ideas and witty discourse, has a visual mastery that can get overlooked. The camera, not the words, unlocks the emotion in his films. In the end, Testament is a not a lament for the decay of Western civilization, but for the fragility of the history and the art that saw it coming — which is hard to separate from the mortality of the filmmaker.

When Norman Jewison was approaching 80, I asked him how long he would keep making movies. “Until the legs give out,” he said, quoting Hollywood director William Wyler. Jewison, who is now 97, completed his last picture at the age of 77. Arcand is the only major Canadian filmmaker to have pushed his career into his 80s. But making Testament, he says, was an ordeal. “It was the first time I was dog-tired all the time. It’s an extremely physical job. Waking up at 5:30 in the morning is pretty rough at my age. And you’re on set standing up until 6:30 at night. I’d rather wake up at eight and read my papers quietly sipping coffee.”

So will he do it again? “I’ve done this all my life, since I was 19. I can probably find something to write. But I’m going to miss the crew, miss the excitement, miss the actors — miss that showbiz side of it, which is very attractive to me . . . We’ll see.”

In other words, until the legs give out.

RELATED: