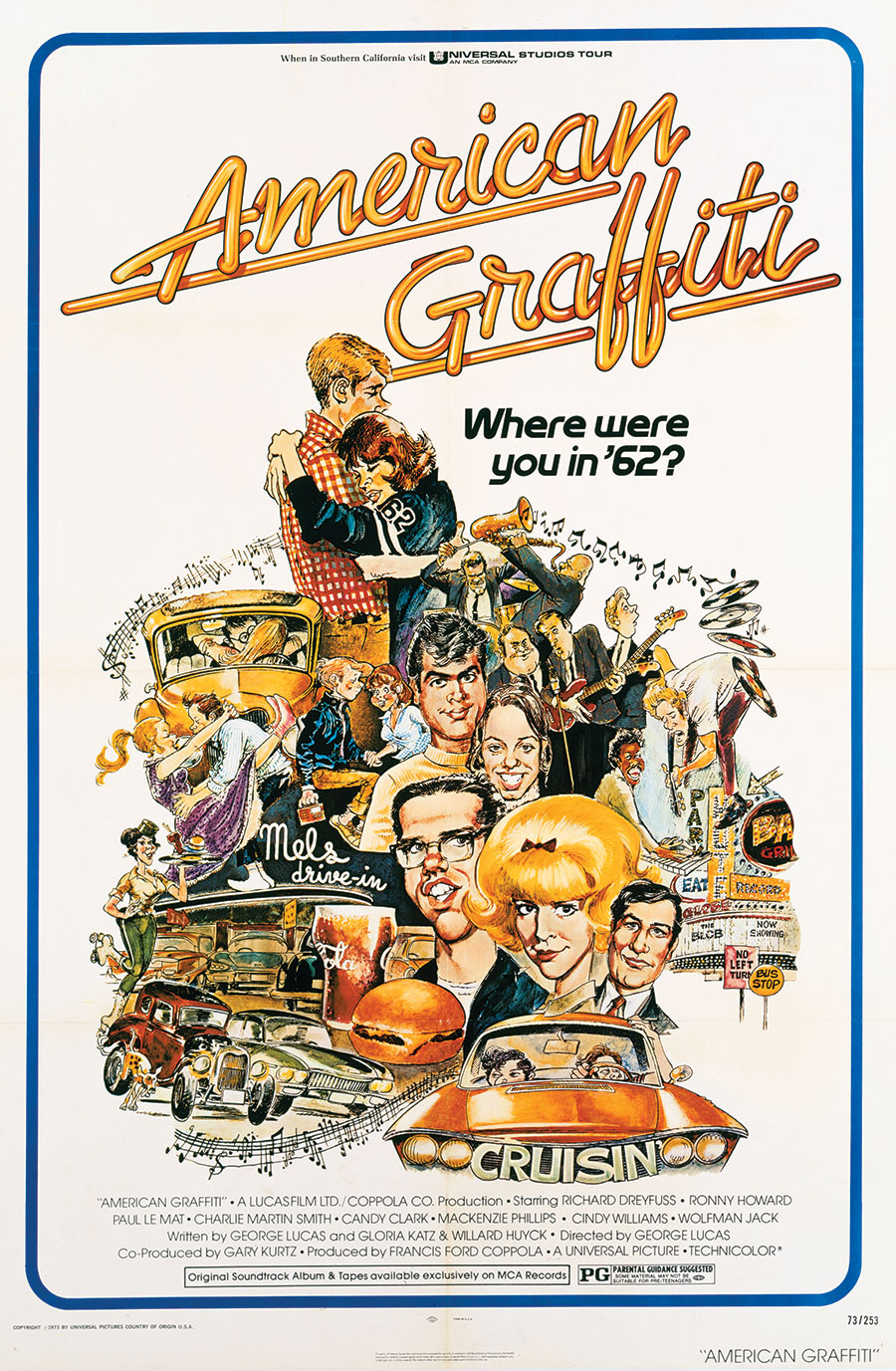

‘American Graffiti’ at 50: How George Lucas’ Classic Marked a Turning Point in Hollywood Filmmaking

Ford with Linda Christensen in 'Americn Graffiti'. Photo: EVERETT COLLECTION INC/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

As American Graffiti turns 50, Brian D. Johnson explains how George Lucas’ classic film paved the way for blockbusters like Star Wars and marked a turning point in Hollywood moviemaking

It’s after midnight on Main Street in the summer of ’62. Two cars cruise the strip side by side, their drivers trash-talking their way into a drag race. In one lane is the hometown anti-hero, a sensitive greaser with a pack of Camels tucked under the sleeve of his white T-shirt. He drives a vintage hot rod, a canary yellow 1932 Ford Deuce Coupe with a chopped roof. In the other lane, a brash cowboy from out of town is itching for trouble behind the wheel of a ’55 Chevy 150, a sullen black sedan that is all business.

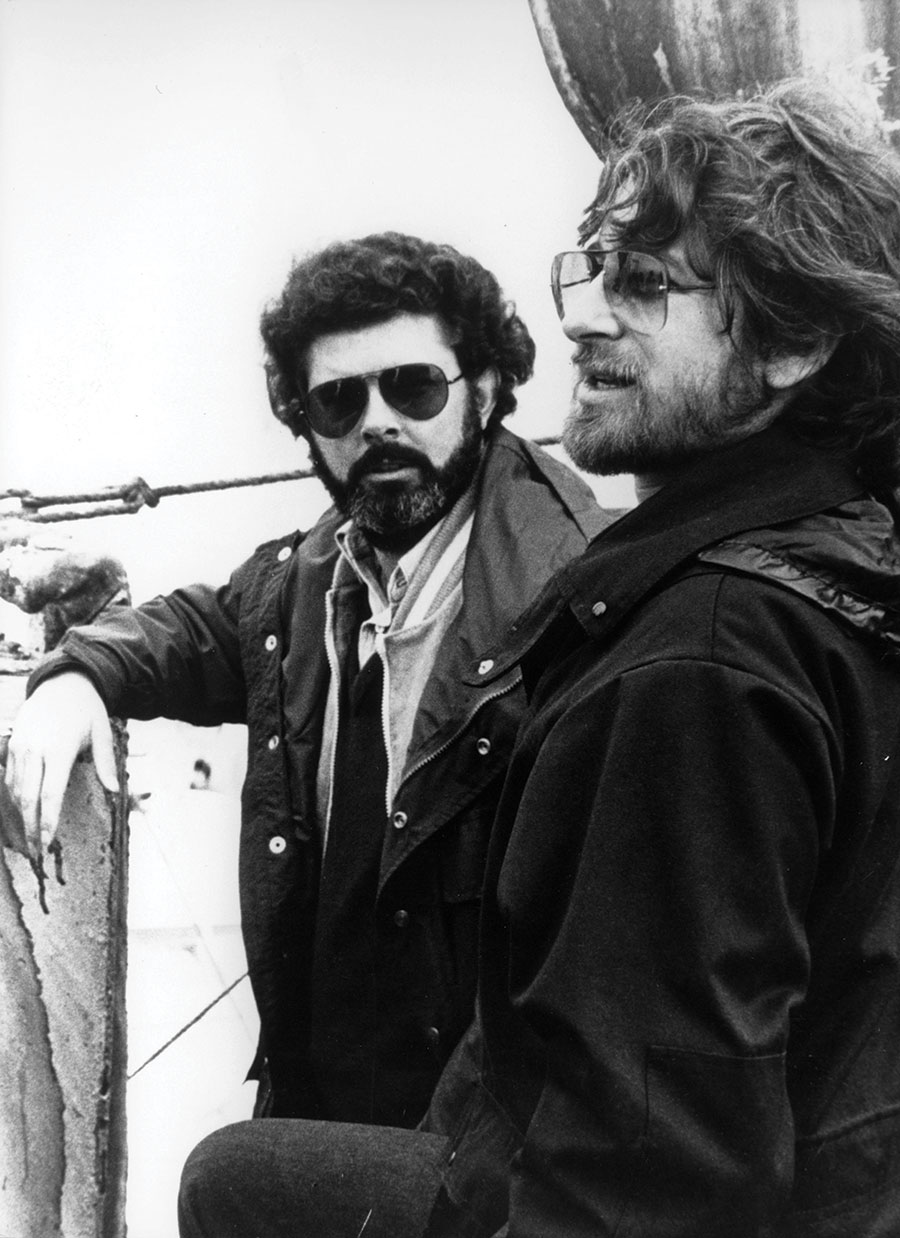

The scene is from the 1973 classic American Graffiti. The setting is Modesto, the California town where the film’s director, George Lucas, was born and raised. The cowboy was played by an unknown actor named Harrison Ford, who was on the verge of giving up showbiz after seven years of bit parts. He almost turned down the role because it paid less than what he was earning as a carpenter. Also, he refused to buzz-cut his long hair into a flat top, so Lucas let him tuck it under a white Stetson – the first, but not the last, iconic hat worn by Ford.

Cast as Bob Falfa, a stock villain who makes his appearance late in the movie, Ford has a minor role. He makes a meal of it. Framed by the car window as he leans into his close-up with a shit-eating grin, he could be channelling Paul Newman in Hud. “C’mon boy, let’s go. Prove it!” he snarls. Then the cowboy blows away the greaser by rocketing through a red light. What lingers is that close-up. In less than two minutes, Ford hijacks the movie with a high beam of pure star power that could melt a hubcap. It would take a while for the world to catch up. Four years later, Lucas cast Ford as space cowboy Han Solo blazing through Star Wars in his Millennium Falcon, a spacecraft festooned with parts from a Ferrari and later dubbed “the fastest piece of junk in the galaxy.” It was the movie that forever changed movies. And it all began with a film in which the stars were cars.

American Graffiti’s far-reaching impact cannot be overstated. And with the 50th anniversary of its release this year, a reassessment of this classic is long overdue. As a lightweight nostalgia trip devoted to cars, rock ’n’ roll and girls (in that order), it may seem inconsequential. In the American Film Institute’s canon of top 100 American movies, Graffiti holds a respectable rank of 62, a notch above Cabaret. It’s not about to overtake Citizen Kane anytime soon. But as Lucas’ first successful movie – and arguably his best – it stands out as a key crossroads in an epic transformation of Hollywood cinema.

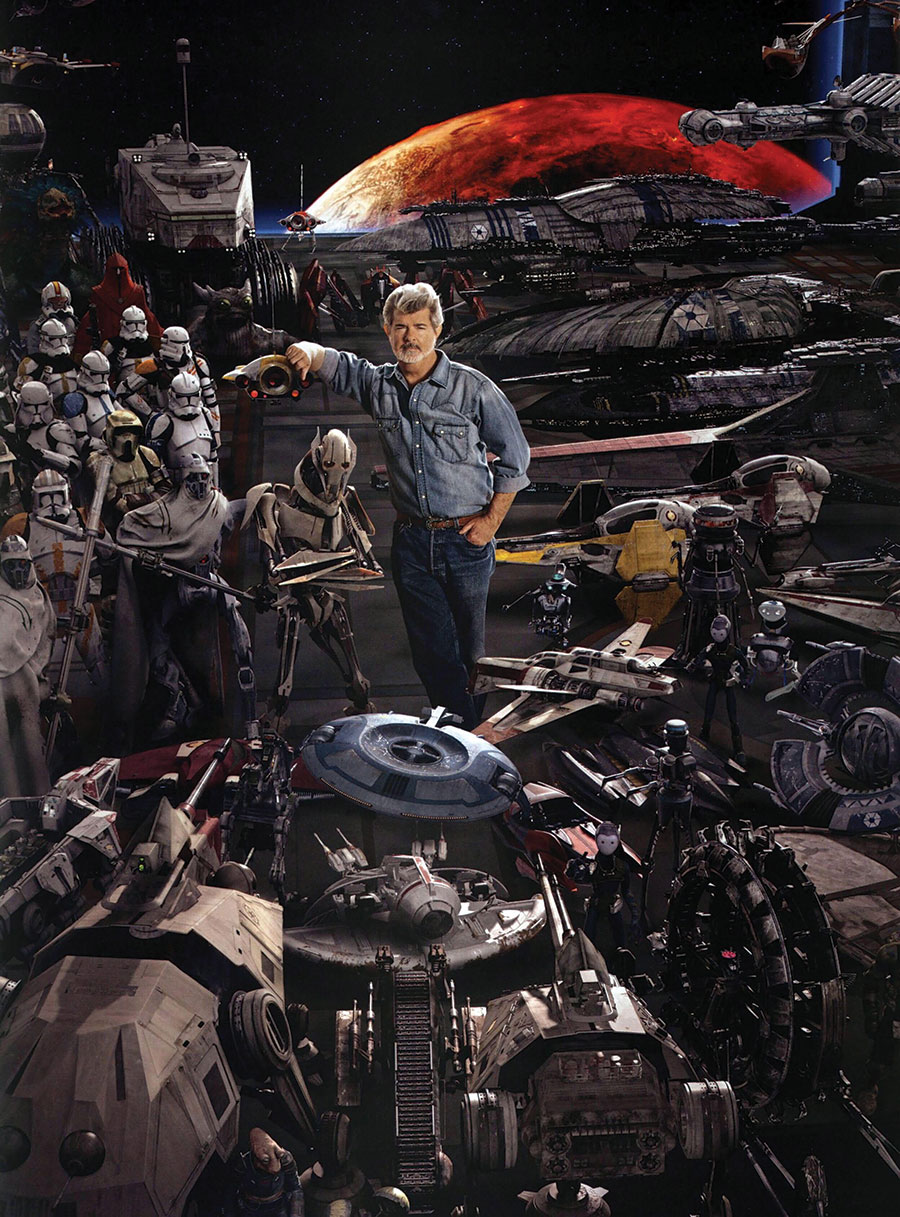

Ford wasn’t the only major star launched from its young cast of unknowns. As Curt, a young man on the make, Richard Dreyfuss honed a character that would become his trademark: the hustler with a switchblade smirk who keeps his wits about him while chasing the American Dream out of bounds. In the next few years, he landed the title role of a Montreal Jew who buys a lake in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Then Steven Spielberg adopted Dreyfuss as his Everyman protégé, staring down a killer shark in Jaws and gazing up at aliens in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Ultimately, however, the most influential star to emerge from American Graffiti was George Lucas. The movie’s box office success gave him the money and clout to create Star Wars, which triggered a seismic shift in the industry. Next he gave Ford a fedora and a bullwhip to create Indiana Jones in Raiders of the Lost Ark, which Lucas dreamt up and produced, but handed to Spielberg to direct. Those two Lucas franchises have endured for more than four decades and, after migrating to streaming platforms, have grossed a combined total of more than US$10 billion worldwide.

Spielberg created the phenomenon of the summer blockbuster with Jaws in 1975, but it was Lucas who forged the prototype for the blockbuster machinery that would upend the business and culture of making movies. Frustrated by his battles with the studios over Graffiti and Star Wars, he colonized their turf, carving out creative and financial control while building his own dream factory of special effects – Industrial Light & Magic. Lucas was not only the Henry Ford who scaled up Hollywood’s last industrial revolution, he was the Steve Jobs who ushered in its digital revolution. For better or worse, he reinvented cinema as a techno medium that led to the world-building supremacy of James Cameron’s Avatar and the superhero monoculture of the Marvel Universe.

As a teen growing up in Modesto, Lucas was a gearhead who loved cars and dreamed of working as a mechanic or race car driver. At 16, he was tearing around town in a tiny yellow Fiat Bianchina, which he’d customized by cutting off the roof, souping up the two-cylinder engine and lowering the windshield. Three days before his high school graduation, he was T-boned by a Chevy Impala driven by a drunk 17-year-old. Lucas was thrown clear before the Fiat slammed into a tree, but would have been killed were it not for the failure of a seatbelt that he had personally installed. It was enough to give him second thoughts about racing or fixing cars as a career. Fortunately, his tech passions extended to art design and photography, which led him to study film at the University of Southern California.

Lucas was among the first generation of American directors to emerge from film schools, along with Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Oliver Stone and Spielberg. At USC, soaking up everything from John Ford westerns to the European New Wave, he became enchanted by film and the contraptions used to create it. The school’s Moviola editing machines were “as comfortable for him as sliding behind the wheel of a car,” writes Lucas biographer Brian James Jones, “with foot pedals to control the speed of the film, a hand brake, a variable motor switch, and a viewing screen the size of a rear view mirror.”

Canada played a crucial role in his evolution as a filmmaker. Lucas became heavily influenced by the experimental documentary shorts coming out of the National Film Board. He developed a singular obsession with Arthur Lipsett’s 21-87, a black-and-white montage of fragmentary images that mixed street footage of New York City with random scraps of celluloid swept from the NFB’s cutting room floor. “When George saw 21-87, a lightbulb went off,” says Oscar-winning editor Walter Murch, who co-wrote Lucas’s feature debut, THX-1138, a dystopian sci-fi thriller set in a robotic society. Lipsett’s innovative editing, which allowed sound and picture to float freely of each other, would lead Lucas to revolutionize sound design. As an in-joke homage to Lipsett in Star Wars, Princess Leia is imprisoned on the Death Star in cell number 2187. And Lucas has acknowledged that the idea of the Force in Star Wars was inspired by a line in 21-87 about a universal life force.

The avant-garde adventure of THX-1138 wowed critics but tanked at the box office, destined to be a cult film among Star Wars fans and notable for launching the career of Robert Duvall. Even Lucas’ wife at the time, film editor Marcia Lucas, complained that it failed to emotionally involve the audience. As she recalls in Peter Biskind’s book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, Lucas replied, “Emotionally involving the audience is easy. Anybody can do it blindfolded, get a little kitten and have some guy wring its neck.” Coppola, Lucas’ partner in the indie production company American Zoetrope, suggested a softer approach: “Why don’t you try to write something out of your own life that has warmth and humour?”

With American Graffiti, Lucas set out to prove he could please an audience. Drawing on his teenage years of cruising Modesto’s main drag, he loosely modelled the film on Fellini’s I Vitelloni (1953), a story of young men adrift at the end of adolescence. He assembled a cast of unknown actors, and after the studio demanded he hire a star, he placated them by drafting Coppola, fresh from his triumph with The Godfather, as a marquee producer. But the film’s real stars were the cars, which Lucas treated as a dance troupe in a movie that he later said was about “the modern mating rituals of American youth who did their dance in cars, rather than in the town square.”

The studio bosses at Universal were baffled and alarmed by his insistence that he was making a musical, which they’d written off as a dead genre. It was certainly unlike any musical they’d seen before. None of the actors break into song. There’s no score. Instead, music blankets the movie as a wall-to-wall stream of top-40 hits, interspersed by patter from legendary DJ Wolfman Jack. American Graffiti was, in effect, Hollywood’s first jukebox musical. And as Lucas and Murch re-recorded the songs coming out of car speakers, gymnasium PA systems and transistor radios, they sculpted a dynamic sound design, innovating the kind of propulsive playlist that would shape movies by everyone from Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino.

Shot almost entirely at night, Graffiti’s story spans a single day in 1962, in a small world ruled by white male adolescents behind the wheel. They are largely models from the ’50s, when cars grew voluptuous curves and rocket ship fins. In an era where flying cars were the ultimate fantasy, these are embryonic spacecraft, vintage dragsters in futurist drag. Actual drag racing is just a plot hook in the film. Most of the time, the cars glide back and forth though the frame in a dreamlike ballet, adrift in the dark like the vessels in 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film Lucas adored. The night shoots gave him a backdrop as black as space. And to light this world, he called his cinematographer, Haskell Wexler, a friend he’d made hanging around the racetrack in his youth. Wexler, who headed a racing team, had filmed Paul Newman in Medium Cool and Sidney Poitier in In the Heat of the Night. Wexler didn’t man a camera on the American Graffiti set, but he lit the cars. Lucas asked him to make his movie look like a jukebox, “very garish, bright blue and yellow and red.”

The cars were well cast. On the verge of being the big man on campus, Steve commands an opulent Chevy Impala, the model that T-boned the director’s Fiat. Laurie, his disenchanted girlfriend, occupies a turquoise Edsel with cat’s-eye tail lights. The tightly wound Curt slums it with a boxy French Citroën “Deux Chevaux,” while the mysterious blond who hijacks his heart with a glance (Suzanne Somers) floats by like a puff of meringue in a white Ford Thunderbird. Graffiti is a costume picture in which the costumes are cars. It’s an early glimmer of the Cinema of Things, where movie stars would be enveloped and upstaged by the invincible glamour of wearable tech – as a Terminator or Iron Man or blue-skinned alien – and every blockbuster would become a toy story.

The multiverse that Lucas would help engineer was still a long way off when he made Graffiti, which is fired with the raw urgency of early ’70s cinema. It’s a less conventional film than it seems. Among its four male leads, it’s hard to pick out a protagonist, never mind a hero, as they change narrative lanes with a fluidity worthy of Robert Altman. More comfortable with machines than with people, Lucas had no interest in directing his actors. Fortunately, he had chosen a talented young cast. Left alone to find their rhythm, they perform with a natural timing and wit, and an authenticity that overcomes the contrivance of the script.

Lucas always maintained he was a documentary filmmaker at heart. Studio productions would typically film a scene multiple times from different angles, but Graffiti’s slim budget demanded speed. Lucas would often shoot a scene with two or three 16-mm documentary cameras running at once, so his actors had no idea when they were “on.” Lucas, whose mantra was cinema verité, saw that as a plus.

Aside from Ford and Dreyfuss, his no-name cast generated a variety of breakout performances. Paul Le Mat – whose portrayal of John, the greaser, inspired the character of the Fonz in Happy Days – went on to star in Jonathan Demme’s indie hit Melvin and Howard (1980). Cast as Steve, the all-American cad, former child actor Ron Howard inched closer to adult roles as Richie in Happy Days before taking an off-ramp to a career as a major Hollywood director. Cindy Williams, who played Laurie, Steve’s impatient girlfriend, found fame as Shirley in the hit sitcom Laverne & Shirley. And, after scoring an Oscar nomination as the free-spirited Debbie, Candy Clark was David Bowie’s co-star in The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976).

Squeezing Hollywood production values out of an indie budget of US$770,000, American Graffiti eventually grossed more than US$200 million and received five Oscar nominations. Its commercial appeal was no accident. Lucas treated the film as a feature-length calling card to show off his chops. It’s detailed with a pastiche of Hollywood archetypes, from the West Side Story jive talk of the Pharaohs grease gang to shades of James Dean in Le Mat’s rebel without a cause. Lucas also unwinds a repertoire of virtuoso camera moves, culminating with the climactic pre-dawn drag race. Yet, he resists turning the film into the kind of heroic fable that would define the rest of his career. The anti-heroes prevail. Terry, the bumbling nerd (Charles Martin Smith), gets lucky with Debbie. Le Mat’s brooding hot-rod king retains his crown only by default, as a blown tire sends the cowboy swerving off the road and the car tumbling onto its roof. Lucas doesn’t kill the cowboy, who is just left deflated and bitter as he walks away from the wreck moments before it bursts into flames.

Pointedly set in 1962, American Graffiti unfolds as a harmless cruise through the calm before the storm – an elegy to the last summer of innocence before the ’60s begins in earnest with the Cuban Missile Crisis, the incoming horrors of the Vietnam War and the cascade of assassinations. It’s a feel-good ride, but something is simmering under the hood. Before the final credits, a text afterword (an innovative device at the time) snuffs out any rom-com sentiments as it spells out the fate of its four male protagonists (neglecting to mention the women): “John was killed by a drunk driver in 1964, Terry was reported missing in action near An Lôc in 1965, Steve is an insurance agent in Modesto and Curt is a writer living in Canada.” American Graffiti’s cryptic title was disliked by both Coppola and the studio, but with that sobering epilogue, it suddenly made sense: The writing was on the wall.

Lucas fully intended his next film to be Apocalypse Now, a project he had originally developed with screenwriter John Milius. Coppola, however, had bundled it into a package deal with Warner Bros., and riding high after The Godfather and The Conversation, he decided it was his to direct. While that rankled Lucas and frayed their already volatile relationship, it was perhaps just as well. A George Lucas version of Apocalypse Now seems unthinkable. And as Coppola lost his shirt in the Philippine jungle, Lucas was able to devote himself to the long ordeal of getting Star Wars off the ground.

He met with resistance from all quarters. Executives at 20th Century Fox were skeptical about the prospects of a sci-fi space opera. (Shrewdly, Lucas low-balled his fee and persuaded them to sign over the sequel and merchandising rights, a concession that would be worth billions.) Meanwhile, his wife Marcia, who was busy editing Taxi Driver, thought Star Wars was beneath George’s talent and kept pushing him to direct the kinds of prestige pictures that Scorsese and Coppola were making. But with Star Wars, Lucas crossed his Rubicon and never looked back. After its massive success, he lost interest in directing, a chore that he found almost as arduous as writing, which he truly hated. Over the next 44 years, he would direct only three movies, all sequels to Star Wars.

Never an auteur in the classic sense, Lucas introduced the era of constructed cinema, of narrative machines that are not written so much as designed and assembled. Now that Marvel has taken over the multiplex, factory-farming superheroes to populate its Escher-like ziggurat of interlocking blockbusters, the old-time integrity of the Star Wars dynasty seems quaint. The Jedi, Indiana Jones and Marvel’s ever-expanding pantheon are all working the same plantation, properties of the Disney empire. And it all started with a space opera fuelled by a nerd’s nostalgia for ’50s cars, comic books and Flash Gordon TV serials.

As a coming-of-age story inspired by the actual reality of Lucas’ boyhood, American Graffiti marks his rite of passage as a filmmaker. It now stands alone as the one truly personal film he has made. Like a last blast of adolescence, it could happen only once and would not be replicated; More American Graffiti, a lame 1979 sequel, fizzled. Whatever the Force did to make that summer night in Modesto come alive onscreen was lightning in a bottle. Now, more than ever, half a century later American Graffiti is the George Lucas movie that transports us to “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.”

A version of this article appeared in the Oct/Nov issue with the headline, “Rearview Mirror,” p. 52

RELATED:

‘The Stones and Brian Jones’ – New Documentary Spotlights The Legacy of the Band’s Late Founder