Tasting the Past, Present and Future in Budapest’s Jewish Quarter

(Photo: Kirsty Lee/EYEEM/Getty Images)

The food scene of Budapest’s Jewish Quarter tells the story of the past, present and future

The Night Beckoned in Budapest.

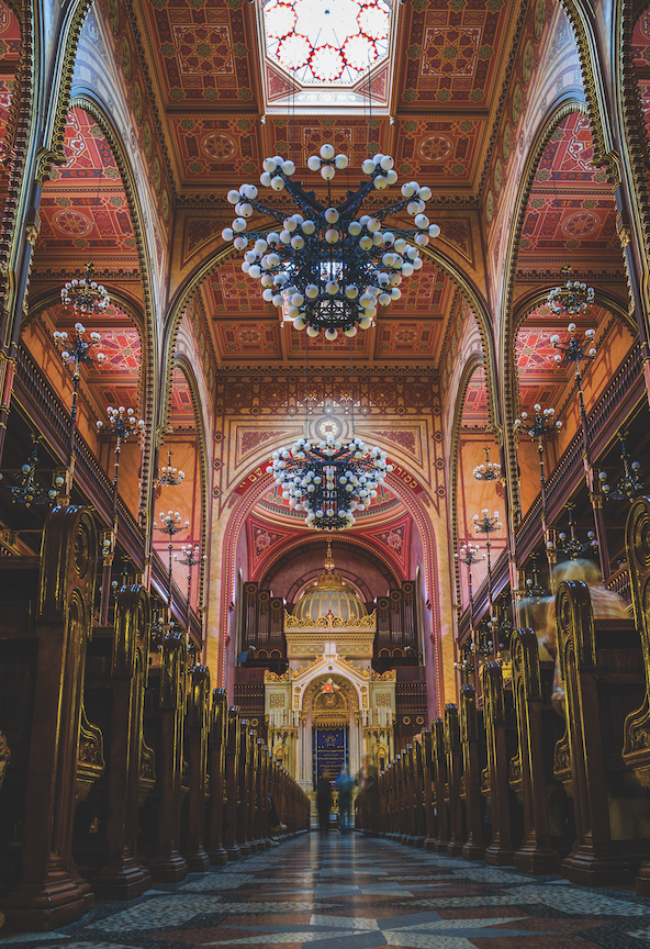

Dinner was on the agenda, but first things first: a trip to the synagogue. Here, now, in a metropolis that had long eluded me but one that I swiftly concluded to be the most underrated capital in Europe — a reservoir of faded grandeur and Wes Anderson-ian panache, complete with ruins and bridges and baths — it proved to be decisive: the Dohány Street Synagogue more than whets a culture vulture’s appetite.

“And that is the Ark of the Convenant,” my guide — a brisk man, economical with his adjectives — told me, pointing to the golden doors on the east wall, said to house a myriad of Torahs saved from Nazi desecration.

Impressive enough from the outside, with its towering Byzantine-Moorish brickwork and its two onion-round domes — wooing the tourists who line up day after day — the interior of the world’s second-largest synagogue was such … it’s like entering a secret void! Frescoes galore. Candelabra aplenty. Ceilings so high you have to crane your neck, and an actual organ that Franz Liszt himself once played. Pews that, notably, comfortably fit 3,000. “And what is the congregation now?” someone else asked.

“About 300,” the guide told us, giving us a best-case scenario while delving into the meaning of those numbers: of Hungary’s prewar Jewish community of 800,000, some 600,000 perished in the Holocaust, and during the Communist era, it was impossible to talk about The Tragedy, as people simply call it.

Religious practice? Not exactly encouraged — and “one of the reasons the Jews here are dominantly secular.” Post-Communist era, he went on, a new generation started to search again for their roots, and it began “a revival that has been going for 20, 30 years.” A revival largely cultural in scope, though gastronomic, too, as evidenced by the fervour in the Jewish Quarter that borders on the Dohány, a boundary of the area that was the Jewish Ghetto during the Second World War.

It was certainly a lot to mull over as I visited the colonnade that hews to the synagogue — now a mass grave for Jews murdered in 1944-45 — as well as, at the back, a weeping willow in metal that inscribes the names of yet more victims on its leaves. Behind the willow tree, the symbolic tomb of Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Jews during those darkest of days.

The mark that history puts on subsequent generations, and the way different cultures gestate was also on my mind as I eventually walked the maze of narrow cobblestone lanes that make up the Quarter now. Destination: Mazel Tov, a blithe, labyrinth restaurant clearly more than happy to lean into its Jewish-ness, both by virtue of its name and its grub. Of all the things recommended to me when I set out for Budapest, going to the Jewish Quarter was (A) on the top of the list (it has a similar vibe to Le Marais in Paris, combined with the hipster hustle of Shoreditch in London), and (B) visiting Mazel Tov was said to be a must.

Going beyond the traditional kosher restaurants tucked in around the area and going that extra mile beyond “ruin bar” (an only-in-Budapest reference to the bars housed in battered buildings in this district), it is a spot that’s been red-hot from the moment it opened in 2014. Harnessing the flavours of Israeli-inspired cooking (with a dollop of Mediterranean) — think shakshuka, grilled meat and hymn-worthy hummus — it also looks back while looking ahead.

Indeed, the first thing I noticed when I sat down — passing through the inner-outer courtyard-like space spiffed up with garlands hugging the walls and twinkling lights lackadaisically hung — was the music of so many languages hovering over the room. Budapest seemed so much more international than I was expecting it to be in the time I had been here but never more than at Mazel Tov — and, indeed, the gay couple on my left, a Swedish-French amalgam (they are based here now), and the two Misses on the prowl on my right who were Brits (both spending a university semester in town), more than made the point. “Don’t miss the eggplant,” one of these ladies steered me.

In a city that is filled with endless character and, like most places, is more nuanced than you might imagine — the architectural breadth of Budapest is made up of Gothic revival, art nouveau, neoclassical, Ottoman — Mazel Tov was also a rebuke to everything you think you know about Hungarian fare, largely thought to be a heavy cuisine. (Think goulash or that street staple that is lángos — typically fried dough, shredded cheese and sour cream!)

With the cold wind of populism also running through Hungarian politics these days with the ascendency of the Viktor Orbán presidency — something else you see in the headlines these days — the restaurant, just one of many New Wave Jewish places, is also an important reminder how complex societies can be. Whether as a response or an exception to, Mazel Tov is a reminder of how gorgeously diverse and outward-looking this Hungarian capital really can be.

As a singer took to the mic and started belting out tunes inside the eatery and I decided to order a second round of eggplant, I was reminded of the inscription in Hebrew that I had seen near the entrance of the synagogue earlier and then later looked up. It read: “And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them.”

A version of this article appeared in the June 2019 issue with the headline, “A Taste of History,” p. 96-98.