Beyond Sunscreen: The Latest Science in Skin Cancer Prevention

We examine the latest research on skin cancer and preventative measures that go beyond your traditional sunscreen. Photo: Naomi Harris

We’ve all cringed at over-tanned skin, hands dotted by liver spots, leathery necks and freckled décolletage, on ourselves and others, and chances are we know someone who has had skin cancer.

Melanoma is less common than basal or squamous cell cancer, but it is deadlier because it is more likely to spread if not diagnosed early. While northern European countries are overrepresented in the World Cancer Research Fund’s top 20 countries with the highest rates of melanoma, Canada comes in 19th, with Australia and New Zealand leading the pack. One of the risk factors is fair hair and light skin, as well as childhood exposure to ultraviolet radiation. But more and more researchers believe skin cancers are being exacerbated by the depletion of the atmosphere’s protective ozone layer, which, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada, has thinned over Southern Canada by an average of about seven per cent since the 1980s.

Last year, about 4,400 men and 3,600 women were diagnosed with melanoma in Canada, with 870 men and 450 women dying from it. These are sobering figures, particularly since risk increases with age. The sun’s ultraviolet, or UV, rays are divided into two categories: UVA (the aging rays) and UVB (the burning rays). Excessive exposure to these rays can damage the DNA of skin cells, triggering their uncontrolled replication and leading to four types of skin cancer — basal and squamous cell carcinomas, Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma. The sun can also accelerate the formation of wrinkles, which result when our body attempts to repair sun-damaged skin with the help of a structural protein known as collagen.

“When we cut ourselves, the skin doesn’t heal quite as nicely as it did before,” says epidemiologist and dermatology researcher Susanne Gulliver, who works at Newfoundland and Labrador-based NewLab Clinical Research, a life-sciences company that focuses on medical dermatology and immune-mediated diseases. “That’s what happens with collagen. With UV damage, the body tries to heal itself and the skin fibres are replaced a little more haphazardly and, as a result, your skin loses glow and elasticity over time.”

Since it’s hard to separate facts from hype when it comes to buzzy new approaches, here’s the latest research on the science of skin care, followed by our guide to the latest in sun care.

Inside Out

You may have heard about the protective qualities of tomatoes, watermelon and papaya, for their high lycopene content, which is a pigment called carotenoid found in red, yellow and orange fruits and vegetables.

Lycopene is also an antioxidant, meaning it inhibits the chemical reaction known as oxidation in our cells that can produce free radicals, leading to chain reactions that can damage cell DNA and sometimes result in cancerous mutations.

In a randomized controlled study of 20 healthy women published in the British Journal of Dermatology in 2010, researchers showed tomato paste containing lycopene appeared to provide protection against acute sun-induced and potentially longer-term skin damage. With such a small study, it’s hard to draw firm conclusions. B.C.-based dermatologist Monica Li is careful to use qualifiers when describing the implications of such research.

“Antioxidants, including possibly vitamins and supplements, may help combat free radicals causing skin cell damage that may lead to skin cancers,” says Li, a medical and cosmetic dermatologist who teaches in the department of dermatology and skin science at the University of British Columbia. “Plant-based foods remain the best sources given current scientific understanding. While only a number of them may be linked directly to reducing skin cancers, dietary oxidants in general can boost the immune response and have been shown to possibly reduce other types of cancers.”

There is also some intriguing research suggesting we have a “skin clock” that can be altered depending on when we eat. In 2017, researchers in the United States and China published a paper in the journal Cell suggesting late-night snacking can reduce the production of an enzyme referred to as Xpa that repairs UV-damaged skin. But, as the researchers point out, the study involved mice, not humans, making it too soon to draw conclusions.

Supplemental Insurance

What about supplements? The short answer, says pharmacologist Steven Hall, is that “there are a million products out there, with too few having any evidence of their efficacy.”

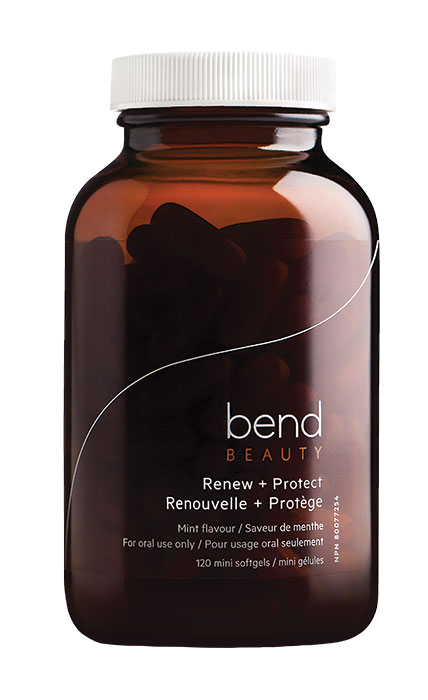

That’s not to say there isn’t some promising, early-stage research. In 2018, the Halifax-based company Bend Beauty published a small study with 28 volunteers who took their oral supplement Renew + Protect — containing the fish-oil-derived omega-3s eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The researchers exposed the volunteers to timed doses of UV radiation before they took the supplement to get a baseline for how long it took their skin to burn. They repeated the test after the volunteers had been taking the supplement for four weeks, and again at eight weeks. The study showed their skin could withstand higher doses of UV rays before turning red.

In 2020, Hall published a follow-up study in the Journal of Natural Health Product Research when he worked for the company as a post-doctoral researcher in pharmacology at Dalhousie University. He tested the product — and some of its individual ingredients — on skin cells known as fibroblasts to see if he could boost resilience to the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

Fibroblasts are found in our connective tissue and produce collagen, which also plays a significant role in wound healing and gives skin added protection from ultraviolet rays. “We did actually find that the

anti-aging formula caused significant protection against both UVA and UVB [rays],” says Hall. “It looks like this is primarily due to the fish oil part of it.”

He suspects it increased the expression of genes that promote antioxidant production, which boosted the resilience of fibroblasts to ultraviolet light. The fish oil may also have reduced production of fatty acid in the skin cells called arachidonic acid, which could theoretically reduce inflammation. “This was only done in cells, which could very well be totally different from what happens in real-life people,” cautions Hall. “However, the results are still very promising, and hopefully similar things are happening in people.”

A version this article appeared in the June/July 2021 issue with the headline “Here Comes the Sun,” p. 76.

RELATED:

Helping Yourself When You Are a Caregiver

Self-Care: 13 Reasons Why You Need More Avocado in Your Life

Self-Care Checklist: Products and Tips to Help Keep You Feeling and Looking Great