Fraud and Older Canadians: What We Can Learn From Those Who Have Fallen Victim

Sophisticated con artists make millions every year from unsuspecting marks and older Canadians are a prime target. Photo: BrianAJackson/Getty Images

The “cybersecurity officer” on the phone had some bad news: A pornography ring on the other side of the world had secretly withdrawn $8,000 from my bank account. He could help me, but only if I acted fast. Within the next three hours I had to buy Google gift cards (which he called “security cards”) totalling $8,000, and he would show me how to use the cards to get my money back. “If a cashier questions the purchase, tell them it’s for your grandchildren,” he said.

Intent on banishing this “porn ring” from my account and my life, I drove to Loblaws and grabbed as many of the cards as I could from the rack, about $2,000 worth, taking instructions from the “officer” via cell phone the whole time.

“Don’t buy those cards,” the man standing ahead of me in line said. “It’s a scam.”

“No, no,” I told him. “The person on the phone is helping me deal with a scam.”

“It’s all part of the scam, don’t you see?”

Poof. Just like that, the spell broke. Porn ring, secret withdrawal, security cards, grandchildren … how could I have been so spectacularly dumb?

This happened in mid-2021. A few months later, acclaimed Canadian novelist Barbara Gowdy wrote a Globe and Mail article describing how she fell for another gift card scam, losing $15,000 in one swoop. It was the same basic script: A “fraud investigator” informed Gowdy that her identity had been stolen and asked her to help nab the culprit. The instructions he gave her made no sense, but Gowdy, 71 at the time, had already cast herself as the heroine in a morality play. She was “Nancy Drew, riding all over the city,” working for the good guys. It “appealed to the novelist in me, as he must have known.”

When it was posted online, the article attracted a string of harsh comments. “No one can be that stupid,” one person wrote. Having read several of Gowdy’s books, I know she is anything but stupid.

By and large, “older Canadians are less familiar with current scamming trends and tools,” says Vanessa Iafolla, a cybersecurity consultant based in Halifax, adding that the “grey divorce” phenomenon — couples splitting up after age 50 — has left many older Canadians vulnerable to scammers posing as romantic interests. “People online are often not who they say they are, and older adults haven’t grown up with this awareness,” she says. “Scammers know this.”

Trending Up

Scams are big business, and the numbers keep climbing. From January to November 2022, the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC) received more than 83,000 fraud reports, representing an aggregate financial loss of $490 million. This significantly exceeds the $383 million tally for all of 2021, which in turn eclipses $165 million from 2020. By the CAFC’s estimate, only five to 10 per cent of victims report a fraud, suggesting the actual financial losses dwarf the reported ones.

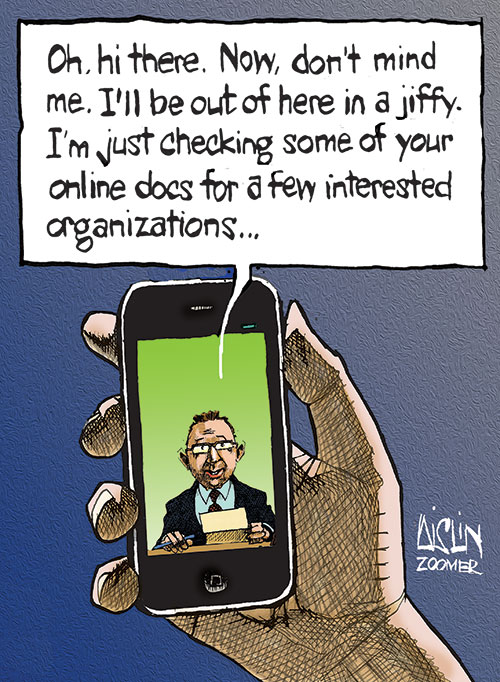

The CAFC, a repository for fraud information managed by the RCMP, the OPP and Competition Bureau Canada, estimates 70 per cent of 2021 fraud reported happened online. Jeffrey Horncastle, a communications officer for the centre, attributes part of the shift to “the changes brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. We’re spending more time online.” In The Confidence Game, a bestselling 2016 book about what makes con artists tick, American author Maria Konnikova writes that fraud victims tend to “give out more personal information on social media” — things like birth dates and check-ins at stores or restaurants — which gives scammers a peek at their vulnerabilities.

One way or another, it’s hard to keep up with the swindles because they keep mutating. Last year’s babysitting scam becomes this year’s gift card scam. The “foreign prince” (who needs help moving their fortune out of their home country) turns into the “destitute mother” (who needs money for baby formula and diapers). When dating apps took off, romance scams quickly followed. Ditto for cryptocurrency investments. COVID, monkeypox, Hurricane Fiona … name a disaster and a matching scam pops up. The practice of phishing, which the CAFC defines as “tactics to trick you into giving personal information or clicking on links,” has also mushroomed in the virtual world. In a classic example, an email or text, ostensibly from Canada Post or a courier company, informs you of a “missed delivery” and instructs you to click on a link.

The top scams that target seniors involve identity theft, investments, romance, rental units and grandparents. In the grandparent scam, “a caller typically informs the target that their grandchild is in trouble, perhaps in jail or in the hospital, and needs money,” Horncastle explains. (It was only a last-minute check with his daughter that prevented my uncle, a retired engineer, from falling for this one.) It’s no surprise emotional appeals work so well. As Konnikova notes in her book, it’s hard to “refuse to be generous to [help] a sick child.” The best scammers make us feel “like we are genuinely wonderful human beings.”

With 46 per cent of 2,000 respondents to the Chartered Public Accountants (CPA) of Canada 2022 Fraud Survey reporting they fell victim to some type of fraud, complacency no longer cuts it. To fight this war, we need a layered strategy that combines awareness with preventive measures.

Security Check

A good nose for scams will take you only so far. If you do any business online, like the 76 per cent of Canadians who, in the CPA survey, reported they visited retail websites, you run the risk that someone will access and sell your data.

“Most Canadians would be surprised to learn that some of their information is likely for sale on the dark web,” says Leigh Tynan, director of Telus Online Security. Not just that, but “only 19 per cent of Canadians who were a target of credit card fraud were aware they were a victim.”

To stay ahead of such scams, review all your credit card statements and report suspicious entries to your bank. Tynan also advises using complex, unique passwords and periodically updating them. For extra peace of mind, consider cybersecurity insurance from companies like Telus, which offers plans that can protect you from identity theft and encrypt data from as many as 20 devices.

As a further layer of protection, you can give a trusted person, such as a grown child, remote access to your computer. (By the same token, you can ask an aging parent for permission to monitor their online activities.) This strategy bore fruit for Toronto marketing consultant Heather Finley, 58, when she learned from a home-care worker that her mother, now deceased, had given out credit card information on the phone. Using remote access software she had previously installed, with her mother’s permission, Finley discovered a discount vacation company had enrolled her mother in a monthly subscription program.

“I don’t know how they found her, but her dementia made her vulnerable to manipulation,” Finley says. After spending an hour on the phone with the company’s aggressive marketers, “I was able to unsubscribe her.”

Recouping Losses

If you’ve succumbed to a scam, you might or might not get all (or any) of your money back. In the first 10 months of 2022, the CAFC was only able to recoup $2.4 million — well under one per cent — of the total fraud losses tallied up over that time period. Even so, it’s worth reporting a scam, not just to the CAFC, but to the police and to your bank, which may have a policy of refunding some fraud losses. That’s how things played out for David B, 80, a retired social worker who lives in Parry Sound, Ont. When his computer froze in 2021 with a message to call a phone number, he shelled out US$300 to fix the computer and an extra US$600 for three years of “protection” before realizing he’d been scammed. He was able to reach the scammers and cancel the service, and he contacted his bank, which put its fraud department on the case.

Whether or not you get your money back, you’ll likely have some emotional equilibrium to recover. “It was so embarrassing,” David B recalls of his fraud experience. “I’ve been in the Air Force a couple of times. I didn’t think I was the type to get taken in.”

Indeed, scam victims face unique psychological hurdles because “their trauma has an element of shame,” says Iafolla, who includes recovery from fraud trauma in her services. As tempting as it may be to bear the shame alone, “the worst thing you can do is to isolate yourself,” she says. “Sharing and support are crucial to recovery.” You can also take heart in the knowledge that, if a brilliant writer like Gowdy could fall for a scam, you’re in excellent company.

A version this article appeared in the February/March 2023 issue with the headline ‘Stop The Scam’, p. 48.

RELATED:

How to Avoid “Grandparent Scams” and Other Threats

‘The Fake’: Zoe Whittall’s Latest Novel Was Inspired by a Real-Life Fraudster