3 Ways to Explore Japan

We explore the land of the rising sun, and the many things Japan has to offer visitors.

1. Checking out Tokyo after dark

I now understand lost in translation. It’s easy to get lost in Tokyo. Its subway map looks like a spider web mashed up with Silly String, yet it runs like clockwork; its street corners a vivisection of crisscrossing pedestrians every which way, yet they all march completely within the lines; the Shinjuku neighbourhood’s alleyways a maze of jewel box-sized booze joints, sushi bars and, well, a few seedy hideaways.

It’s raining, it’s midnight and we’ve just jumped out of a taxi from the Park Hyatt, where we played our best Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson at its sky-high lounge. But the sky was full of thunder, grey billowing clouds that blocked the view of bright lights and big city. Time to take it to the street.

And street we do. The taxi driver, too, seems lost, and circles more than once in an effort to drop us off somewhere that he deems a good spot to let go his foreign cargo. But, heck, we’re lost anyway, in one of those neighbourhoods, Golden Gai.

The alleys here are, at most, 10 feet wide; at its narrowest, it’s a stretch to stretch our arms to their widest wingspan. This rabbit warren of seven streets laced together through the cheek-by-jowl drinking holes—more than 250 of them—has a Blade Runner vibe under the pouring rain, but inside there’s an intimacy that some might find claustrophobic.

Some of these places seat fewer than six; some of them allow smoking, most don’t open until after 8 p.m., and stay open until the wee hours of the morning; all inspire conversation. Heavily tattooed lady barkeeps pour shots while businessmen, bikers and the odd couple—Japanese and foreign—all sit elbow to elbow. We prefer to walk and window shop, so to speak.

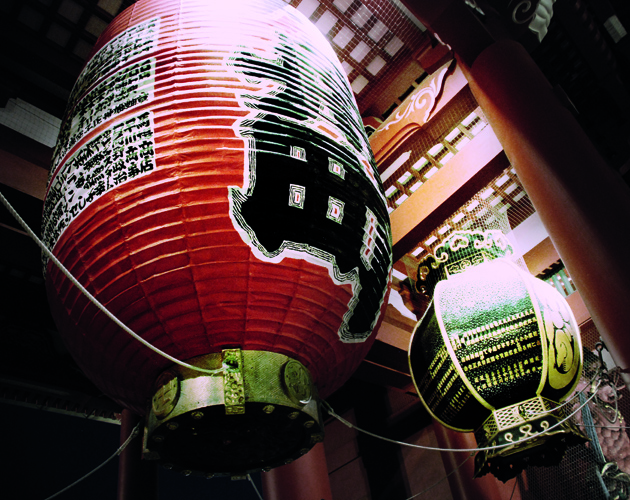

Observing this city after dark and this close to the ground is a marvel in itself. Skyscraper beacons are replaced by paper lanterns and neon signs, in both Japanese and English; sandwich boards and painted doors describe what’s on tap inside, as gritty as it seems, there’s still an art to the presentation. Some have a luxe edge to them and request a cover charge—the cheap wine makes up for the entry fee—while others give off an attitude of “I dare you to come inside.”

Artists and writers congregate here, as do tourists looking for less Harajuku girl/anime/kitch and, perhaps, the less-polished side of Tokyo. It is a small slice of cultural chaos in an otherwise structured world. But it, too, is fleeting. Once the immersion becomes overwhelming, we feel a need to come up for air. A few minutes later, we head on to the Grand Hyatt hotel in the high-end Roppongi Hills and, there, the throaty vocals of a live jazz singer calm our overloaded senses.

Next: The art of zen

2. Discovering the art of zen

It is time to breathe. Deep. The art of Zen was founded here and, after a high-speed train ride from Tokyo to Kyoto, I am waiting to exhale. At the Shunko-in Temple, the vice-abbot is guiding a meditation class. He’s a practising monk, with roots in Japan but an American education. His manner is easy, a reflection of his surroundings. The temple is all earthy greens, tatami-straw browns and water-colour murals, nothing jarring to the eye.

I sit on a meditation pillow to ease the pressure on my knees while in a cross-legged pose and take a breath. The vice-abbot demonstrates: his method is easy, he says. Find a focus point and keep your eye on it or close your eyes, whichever works best. Then, inhale for a count of five; then exhale for a count of 10. Or whatever number you count to breathing in, you simply double it breathing out. That’s it. It will enable you, he adds, to centre the focus on your breathing and nothing else for those 15 counts. I have never really been able to meditate. But, when stripped away of all the new-age chatter, it’s not as challenging. I can do this. And I do, for about 10 minutes. I am refreshed, grounded, calm.

Just outside the classroom, a Zen garden is our view, and our teacher explains the plantings have been arranged to represent the coastline of Japan, complete with islands. The gravel, engraved by a rake with swirls and lines, represents the sea. A calm sea.

The feeling stays with me over the course of the day. Visiting Kyoto’s golden Kinkaku-ji Temple just as the sun dips below the horizon, I take a moment to meditate on its sheer beauty. Glorious in its glow, light bouncing off its curves and angles, its reflection in the lake on which it sits almost as luminous as the real thing. I can’t take my eyes off it, a focal point worthy of meditating upon, a testament to the constant striving for perfection that imbues the Japanese ethos, whether it’s a box of chocolates wrapped in exquisite hand-dyed paper and silk ribbon or a temple where the worship of ancestors, form, function and beauty all come together.

Next: Touring the gardens

3. Visiting the immaculate gardens

Another train, and we are in Kanazawa, where, surrounded by ancient pines, I feel lost in the woods though I’m not at all. In the way a silken obi belt ties together the most exquisite kimono, here, form, function and beauty come alive. I’m standing in Kenrokuen, considered by experts to be the third most beautiful garden in Japan. If this is third, then all I can say is the first and second must be mind-blowing. It’s autumn here and, although the trees lack the sheer colour ex-plosion of our Canadian varieties, there is colour nonetheless. Burnt orange leaves, fern green pines, near-black ponds and pools provide striking contrast.

Everything is mapped out, meaningful. The gardeners and nature’s caregivers have meditated on this piece of land, all 11.4 hectares of it, wrapping the plants, flowers, trees and sculptures around the soft curves of the ponds and lakes and along the harder edges of the river that runs through it. Tree branches are held up by golden strings, as some, upwards of 80 years old, need the leg-up of protection against the weight of rain and snow. But it is beautiful, artful, the strings a pyramid-like extension of branches, all in harmony and balance with the earth tones and pale-sky backdrop.

I am no longer lost in translation. I am just lost. In the moment.

If you go www.ilovejapan.ca. Air Canada has daily flights to Tokyo’s Haneda and Narita; business class offers Vancouver celebrity chef David Hawksworth’s culinary creations. Editors’ tip: Haneda is closer to Tokyo’s centre. www.aircanada.com

A version of this article appeared in the June 2016 issue with the headline, “The Art of Zen: Japan Three Ways,” p. 60-62.