A Good Death: My Father’s Decision to End Dialysis at 81 Freed Him to Enjoy His Last Days

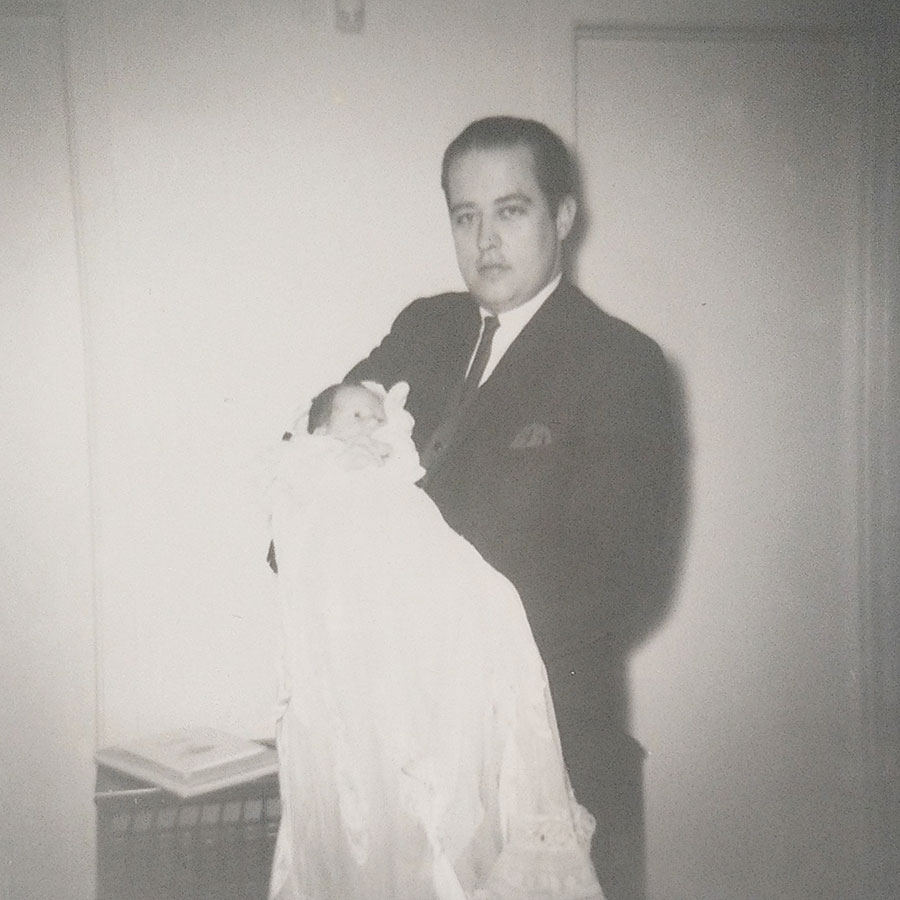

The author with his father on his christening day in 1968. Photo: Courtesy of Bert Archer

My dad had been dying for decades. Ashley Archer, the broad-shouldered, thick-bellied former football player and air force medic who met a woman one night skating in Montreal and turned his life upside down for her, and then me and then my sister, was sick as long as I knew him. One of my first memories of him is a growing red splotch on a bed sheet, an ambulance and something about hernias and stitches. He smoked for 40 years, ate his whole life like the famished farm boy I only lately realized he never stopped wanting to be and lost all of his money and most of the will to do much of anything after my mother died 35 years ago.

Now he was 81, on dialysis, mostly immobile, and I’d been preparing for his death for some time. I travel a lot for work and had put aside an Aeroplan account specifically for the inevitable emergency trip either to my dad’s deathbed or his funeral. Sometimes, I’d catch myself composing lines for a eulogy, concerned that when the moment came I might not be able to come up with anything good. It was all about preparation in advance of the sort of last-minute vortex that generally follows what doctors call multiple morbidities – my father’s horse race of illnesses and conditions nipping at each other in the final stretch. I wanted to be ready.

The Call

The call came in November, and it was exactly what I’d pictured: my sister on the phone, her voice in a quaver, telling me Dad was in the hospital and had a 10 per cent chance of surviving the weekend.

He’d been in ambulances and hospitals a dozen times in the last few years, but this was different. My sister, primary caregiver and lead father-wrangler in my absence – the older brother who flew several thousand kilometres east after high school and never returned – lent him an ear when he needed to share problems and the increasingly sexist and occasionally racist opining we’d both long stopped trying to square with the strident labour activist and union steward we grew up with. She’d grown clear-eyed about these health crises. So the wobble in her voice elbowed me in the solar plexus. This was it. I opened the Aeroplan app on the phone while we were still talking and, within three hours, boarded my flight, still with enough points left over to fly my boyfriend, who cancelled his week to meet my dad for the first and possibly last time.

My father wasn’t in any pain and was perfectly alert. It was a twisted bowel, they said, that got infected and was slowly making him septic. So we sat by his bed, I introduced them, both aware of the situation and both a little tongue-tied. I tried to get Dad to tell a story about my childhood or about his air force job helicoptering out into the forests of northern Ontario and Quebec to retrieve the often vestigial remains of unlucky Avro Arrow-era test pilots. Macabre, maybe, but one of his best stories. I was glad they were in the same room together, that in years to come, my boyfriend would have a picture in his mind when I talked about my father, but it was all a little awkward and more than a little forced. Meanwhile, I was slaloming down hallways talking to nurses and doctors, calling my sister about insurance and funeral plans, worried that there was something I still needed to talk to him about, or he to me.

And then he got better.

I was relieved but I immediately projected myself into the near future to wonder about when the next call came or the call after that. Would I jet off every time? And what if I didn’t?

The Decision

Death is a mess. It’s expensive, it’s disruptive, it gets in the way and then makes you feel terrible for thinking any of that.

And then six months later, the real call came. But it was from my dad this time.

Me: “Hi, Dad.”

My dad: “I seem to be getting messages. You called me.”

Me: “Nope.”

My dad: “No? Well, there you go. I just talked to my doctor about ending dialysis.”

His dialysis had been eating up three of his hours a day, four of his days a week. The rest of the time, he was in bed or in a wheelchair due to nerve damage caused by Type 2 diabetes and his initial refusal to make the necessary dietary concessions. He’d been years without the cake and ice cream and sugared teas and coffees he loved to the point of compulsion, but the damage had been done; he could no longer feel his feet and only the tips of a few fingers, cutting him off from much of the touch-screen world he’d survived to take part in. His heart didn’t always beat as it was expected to. He was fat. His evanesced football muscles had become a drapery of grey skin.

Me: “That’s good to hear, Dad. I’m glad.”

It might have seemed gentler to tell my father he shouldn’t give up. He still had things to look forward to. But it wouldn’t have been true. If he thought it was time, it was time.

According to Toronto gerontologist Dr. Mark Nowaczynski, my dad was actually in a pretty good position and had made a sound decision. He figures he has had 100,000 doctor-patient encounters in his career, with the average age of those patients being well into the 80s; 40 per cent die or enter long-term care in any given year.

He explained how it usually goes down: you’ve lived a long life, but things are braiding themselves into something that looks like a conclusion. Those comorbidities. It could be congestive heart failure, a urinary tract infection, hypertension, constipation. And then up from behind, pneumonia, the stalking horse.

“It’s Tuesday afternoon, and my office gets a call that Mr. So-and-So is coughing and short of breath. He says he won’t go to hospital. I put him on antibiotics. He’s starting to get better on Friday. Crisis averted.”

Family is taken off alert, emergency travel plans are cancelled, life resumes. And then Sunday morning, he’s dead.

“That’s the typical. It doesn’t wait for you to prepare. Your father’s situation is the exception rather than the rule.”

Fear of Dying

And yet, despite this, my father’s nephrologist, Dr. Kevin Horgan, told me my father’s decision was a rare one. He didn’t want to speculate on why that might be, but I will: we’re thanatophobes. Avoiding death when it’s avoidable makes sense; pretending not to see it when it’s staring you in the face, talking past it like an offensive brother-in-law you hope will get the message and leave is nonsense. Decisions like my father made are sometimes described as brave, but much as I loved him, my father was not a brave man. He did pride himself on his common sense, though. And I’m happy, proud, that it didn’t fail him at the end.

About a year before my dad’s call, the Globe and Mail ran a couple of stories about chosen deaths. One was about the Australian botanist David Goodall who was healthy and 104 but didn’t want to be, and the other was novelist Lawrence Hill’s generous essay about his mother, Donna, who was 90 and had tried several times to end a life she was done with. Both had to spend tens of thousands of dollars to go to Switzerland to get the sort of conclusions they wanted, he drifting off as the timpani and strings in Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” chorus crashed together into the composer’s most famous fermata, she listening to a song by her other son, Dan Hill, which ends with “You’ve got to hold on to yourself or else you’ll fade.” Both seem a better exit cue than the bark of a crash cart crew.

We may be some distance from what they’re doing in Switzerland, but it seems the death my father chose is within reach of a lot of Canadians with a little non-magical thinking, along with a little friendly advice and maybe a legislative tweak or two.

The Letter of the Law

As we talked about being old and coming to see death as a not-unwelcome part of life, Nowaczynski told me the story of a patient to whom he’d provided home care about a decade ago. While frail at the age of 93, she was otherwise fine, healthy and could have chugged on for several more years. Like Hill and Goodall, though, she decided she’d had enough. She considered her options – she was not wealthy, and so Switzerland was not a reasonable option – even trying a few, before she decided to simply stop eating. Instead, she sipped Champagne – Veuve Cliquot, Nowaczynski recalls – just enough to moisten her mouth, until she slipped painlessly into a coma and died at home.

Though the law in Canada is more generous than in many places, the 2016 laws surrounding what’s called medical assistance in dying (MAID) are still more restrictive than we should be willing to put up with. Restrictions like required second opinions and a cooling-off period during which the issue may become moot are reminiscent of women’s struggle to win the right to decide if they want a fetus in them or not.

Until we manage to muster the sort of political resolve necessary to advance this part of the right-to-choose spectrum, there is comfort to be taken in knowing that the simple act of refusing food is always available. Hill offered another end-of-life strategy, one his mother had attempted before Switzerland, though she, like many of us, was missing one crucial bit of folk wisdom. She’d sat out on her garden patio on the coldest night of the year, having heard freezing was one of the more pleasant ways to die. But all she got was cold. When she told the story a few minutes before opening the valve that would release the barbiturates and offer her a faster version of the Champagne lady’s tipsy death, the doctor told her she’d forgotten the booze; a bottle of her favourite spirit – which handily makes you feel warmer while further reducing your body temperature – would have done the trick. His mother laughed, Hill wrote, conveying the mood in the room, so far from the miasma that covers other rooms in other countries where death has to sneak in rather than be welcomed as an invited guest. “I’ll remember that next time,” she quipped.

Nowaczynski offered another bit of advice he’d not been able to provide a patient without the aforementioned approval process as it could be construed as assistance in dying. “If you’re going to overdose on drugs that are sedating, drink some good Cognac with it or whisky; the interaction is much worse,” by which, he acknowledged, he meant better.

Final Pleasures

My boyfriend and I booked another flight and spent another few days with my father. Not anxious days this time but friendly ones and calm. The three of us had supper at Luther Court, his assisted-living home, with my sister and her daughter. I asked if there was anything he’d like to do that he hadn’t been able to do. I had been in Grade 8 and free for a weekend from boarding school the last time he and I had taken high tea at the Empress in Victoria. He’d never been since. He wanted to see the old hotel again. I booked a wheelchair-accessible car, and the three of us – my father, my boyfriend and I – had an extravagantly diabetic-unfriendly tea, with seconds on all the cakes and biscuits he liked best.

This was a freedom he’d won since deciding to stop his dialysis. He’d enjoyed few freedoms recently, having lost his independence, mobility and continence. Now, at the end, he clawed back his culinary freedom, the simple, wonderful gustatory pleasure of sugar and fat, with an enthusiasm and joy I hadn’t seen brighten his roughly shorn face in years. As I followed his caregiver, a young, careful and conscientious man out of his room and down the hall, a fellow resident, a woman roughly my father’s age, asked with envy in her voice about the cake and fruit she’d seen on his meal tray. “Oh, Ashley’s diet’s off,” the caregiver said with a gentle smile. “He can eat whatever he wants.”

I smiled, too; I’d never been a fan of trading treats for time. But as that woman’s disappointed face retreated back to her room, I was sure telling an 85-year-old not to eat an éclair in the tone you use to scold kids about coffee or tobacco or pot is doing no one any favours and doesn’t make much sense. I felt like going out and buying a big box of vanilla slices from the Dutch Bakery down on Fort Street and playing candy man. I didn’t.

A Good Death

The next day, before flying out, I stopped by my father’s room to say goodbye. I’d tried to think of questions I’d be sorry later not to have asked him or of anything I wanted him to know about how I felt about him. But I’d asked all the questions, said all the I love yous and given all the thanks for upending his life all those years ago, for the summer-long family road trips across the continent, for covering the walls of my bedroom with a thousand books, for putting his Latter Day Saints faith on hold for more than two decades so my mother’s intransigent Catholic parents would let them marry. So we just sat, he in his wheelchair, me across from him, and smiled.

In the middle of a silence, he said, “The time has come, the walrus said …” It was a line yanked directly out of my childhood, one I associated as closely with him as I did my mother with “Heavens to Murgatroyd.” I hadn’t heard either in 35 years; his verbal playfulness mostly died as my mother lay for weeks slowly losing her bowel, liver and mind to cancer. It was his exit line, when he wanted to end a dinner he was done with or a conversation he was no longer interested in. I got up, put my hand on his shoulder, bony now but still broader than mine will ever be, and kissed him on the cheek and then kissed it twice more, something I’d never done. It was a final moment, one that too few people are able to have, to occupy, to realize, to enjoy. He’d see my sister and his granddaughter a few more times, but his time with me was done, nothing left unsaid, nothing unfelt, regretted, missed.

Over the next 10 days, the sodium, calcium, phosphorus and potassium building up in his blood, which the dialysis treatments had helped to flush out, made him increasingly sleepy. Sometime on the seventh of June, he fell asleep. Three days later, there was enough potassium to start playing tricks with the electrical currents that had been shocking his heart into beating 100,000 times a day for 82 years, five months and 18 days and, a few months shy of what would have been its three billionth beat, his sinoatrial node didn’t get the charge it needed to squeeze anything more out of the walls of his atria, and his heart finally stopped.

It was a good death, the kind that we should work to ensure becomes the rule, not the exception.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2020 issue with the headline, “The Decision,” p. 59.

RELATED:

Archbishop Desmond Tutu Advocates for Assisted Dying on his 85th Birthday

The Right to Choose When: Audrey Parker Exposes Flaw in Assisted Death Law in Final Days