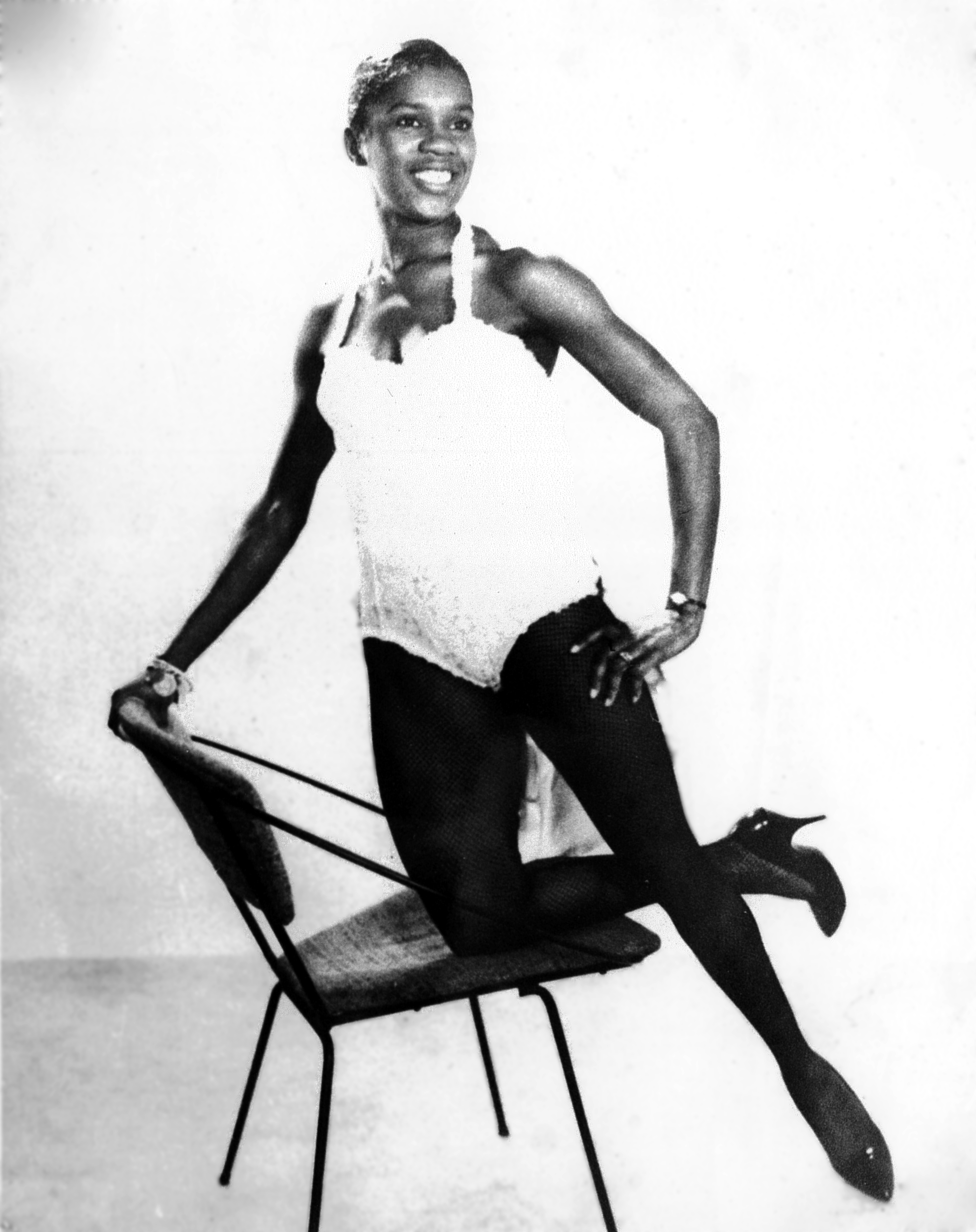

Montreal’s Ethel Bruneau, 84, Is the First Hoofer to Tap into the Canadian Dance Hall of Fame

Photo: Courtesy Ethel Bruneau

Ethel Bruneau has been a storyteller all her life. The tales flow from the tappity-tap-tapping of her shoes. “In tap dancing, you talk with your feet,” she says, pausing for a beat. “My feet have told a lot of stories.”

Bruneau, 84, is a dance legend in Montreal. She’s been hoofing since she was a three-year-old in Harlem. She danced at Carnegie Hall and on The Ed Sullivan Show. She danced alongside musical masters like Oscar Peterson and Fats Domino. And for 60 years, she has been a teacher and mentor to generations of Montrealers, spreading a passion that shows no sign of slowing.

Watch: Bruneau recalls trying to sneak into the Apollo Theater in Harlem

“I’m always going to keep moving. When you love something, you just want to keep doing it,” says the grandmother of five. “What do I care about age? It’s just a number.”

Now the queen of tap is adding a jewel to her crown: She is the first tap dancer to be inducted into the Canadian Dance Hall of Fame.

“When they first called me, I said, ‘Are you sure you’ve got the right lady?” she says. As reality set in, she was thrilled. “It means the world to me.”

Bruneau’s love affair with tap began when her mother sent her as a pre-schooler to the Mary Bruce School of Dance, a Harlem landmark in New York City. Bruneau was instantly smitten. Soon she was immersed in an effervescent tap scene that included luminaries like Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Sammy Davis Jr. and Gregory Hines. By age 9, Bruneau was tapping with her cousin Poppy in Atlantic City. One day when she was a teen, she went along with a friend to an audition to perform with the Cab Calloway orchestra.

“A lady in charge came over to me and said, ‘Well, what do you do?’ I said I just came with my girlfriend,” Bruneau recalls. The woman got Bruneau up and showing her stuff. “I was singing, swinging and tapping.” Next thing she knew, she was asked if she wanted to go to Canada.

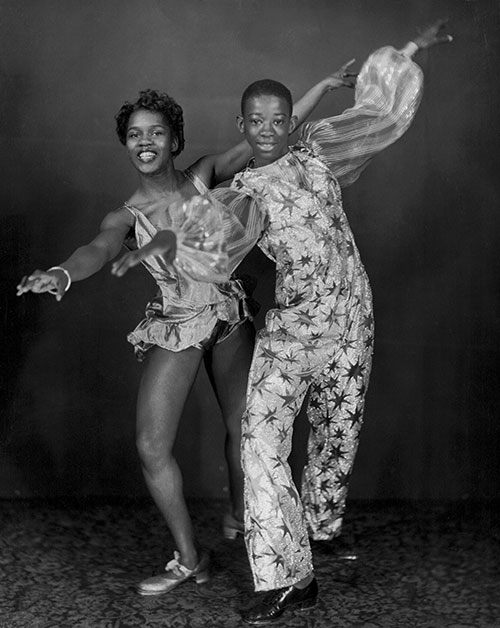

Bruneau arrived by train in Montreal for what was supposed to be a three-week stint and never left. She got work performing at nightclubs like the Montmartre, the Mocambo and Maroon Club, names that evoke the city’s free-spirited years as the Las Vegas of the North.

Bruneau keeps mementos from her singing and tapping performances stuffed in cardboard boxes in her home on Montreal’s South Shore, their contents a trove of ‘50s and ‘60s memorabilia — like the lime-green lamé pantsuit with matching halter top and orange feathered trim that she wore on stage.

“Montreal was crazy then. We did our shows and then we’d see our friends’ shows. It would go all night,” she says. “Nobody was looking at my colour. I was just ‘la chanteuse, la danseuse, Miss Swing!’”

Now she calls herself an apostle of tap. Bruneau has taught hundreds of students the shim-sham, brush-drag and triple-time-step since she began giving lessons in a friend’s suburban bungalow outside Montreal in the early ‘60s. She shifted locations through the decades and, after recently closing her dance school, continues to teach classes in shared studio space in Montreal.

Watch: Bruneau explains why dance is such an important part of her life

One day in early March, she was standing before three young students in the Montreal studio, rapping her cane on the floor to a rhythmic beat while her protégés went through their paces. Undiminished by arthritic hips and double-bypass surgery, Bruneau is a commanding but affectionate maestra.

“Swing it up!” she exhorts. “Bend! That’s why we have knees!”

Bruneau has poured her heart and soul into tap, as well as her own assets, mortgaging her home four times to hold tap dance festivals in Montreal. She watches DVDs of old musicals in her bedroom to study the moves of Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, sitting on the edge of her bed and tapping out the moves with her feet.

“Dancing is good for your brain,” she says. “I wish I could teach everybody how to dance.” She has no plans to slow down, repeating to whoever will listen that she intends to depart this life with her tap shoes on. After all, she says, tap has been good for her.

“I never needed a shrink. Dancing has always been my therapy,” she says. “It always made me happy and it still makes me happy.”

Her acceptance into the Dance Collection Danse Hall of Fame is a poignant milestone for Bruneau, whose lifelong passion has even been passed down to four tap-dancing grandchildren. The ceremony, originally scheduled for the end of March in Toronto, has been postponed for a year due to the coronavirus pandemic, but the distinction remains. “I feel honoured. It’s taken a long time to get tap dancing recognized,” she says. “Tap is as good as ballet, it’s got just as much technique. The only thing is that you can do tap until you’re 100.” And the Queen of Tap plans to keep showing us how to do it, telling its story with her feet.

RELATED:

From Depression to Parkinson’s Disease: The Healing Power of Dance

10 Music Legends Who Redefined Aging in the 2010s

64-Year-Old Runner Isn’t Letting a Stroke Slow Him Down as He Trains for Next Marathon