Jennifer Hosten, the First Black Miss World, Recounts Her Historic Win in Memoir

Miss World host Bob Hope crowns Jennifer Hosten at the 1970 Miss World competition as runner-up Pearl Jansen, Miss Africa South, stands beside her. Photo: Sutherland House

As 22 million people tuned in to a BBC TV broadcast on Nov. 20, 1970, host Bob Hope kicked off the much-lauded Miss World pageant at London’s Royal Albert Hall with this joke.

“I am very happy to be here at this cattle market … mooooooooo,” he quipped. “It’s quite a cattle market. I’ve been back there checking calves.”

Although it is shocking today, it was even more shocking then to the feminists who had infiltrated the audience, ready to take a stand against the objectification of women in a beauty pageant where, in the bathing suit competition, contestants were asked to turn around on stage and show their bottoms to the audience.

“I don’t want you to think I’m a dirty old man ’cause I never give women a second thought,” Hope continued. “My first thought covers everything.”

The Women’s Liberation Movement members planned to disrupt the proceedings when the pageant’s competitors were on stage in their swimwear, but they were so enraged by Hope’s opening lines that one woman sounded the alarm early, and they pelted the stage with flour and stink bombs. Police arrested five women, and the slightly tarnished pageant continued.

At the time, racial tensions were building around the globe, and South Africa’s apartheid-run government was making international headlines after it was officially expelled from the Olympics in 1970. It culminated in the country sending two finalists: one white, under the banner of Miss South Africa, and the other Black, under the banner of Miss Africa South.

England itself was experiencing a booming population growth fuelled by loads of immigrants from places like the Caribbean. Housing and job shortages were contributing to the country’s unrest as it recovered from a paralyzing national strike by coal miners in 1969. Race and clearly gender struggles were simmering.

If there was ever a time for the entire world to be truly engaged in the results of Miss World, it was Nov. 20, 1970.

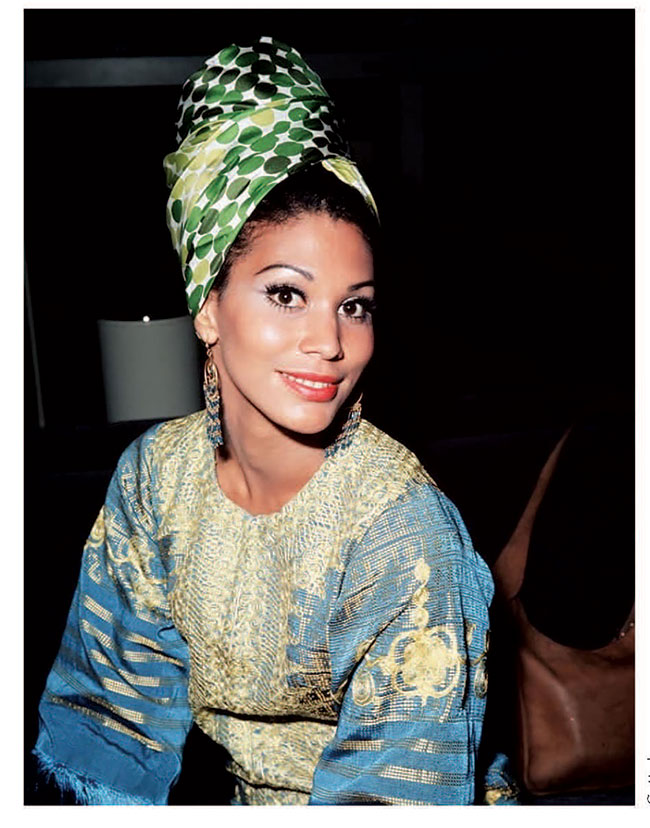

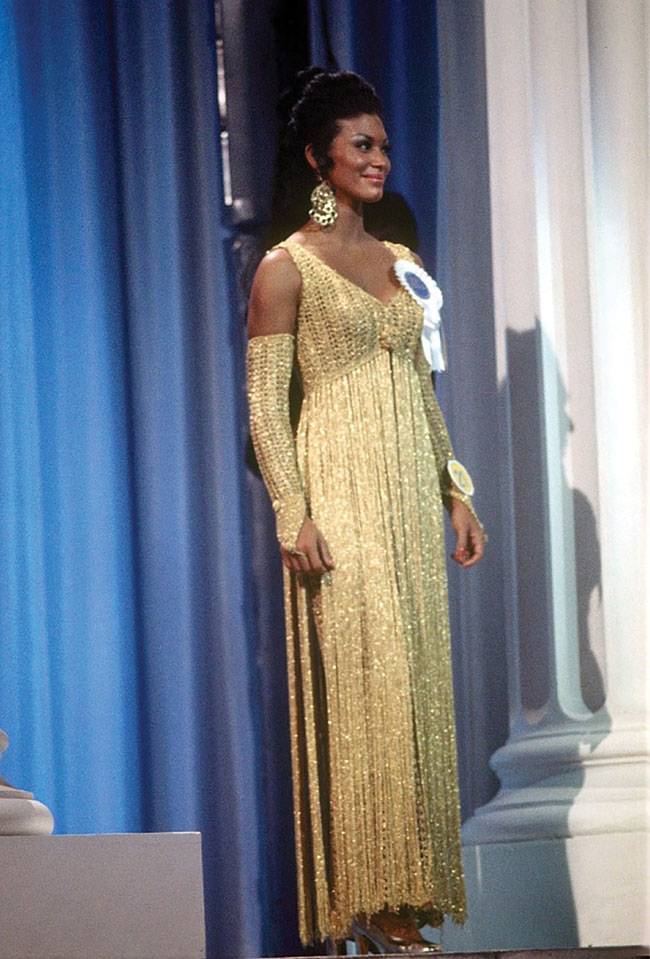

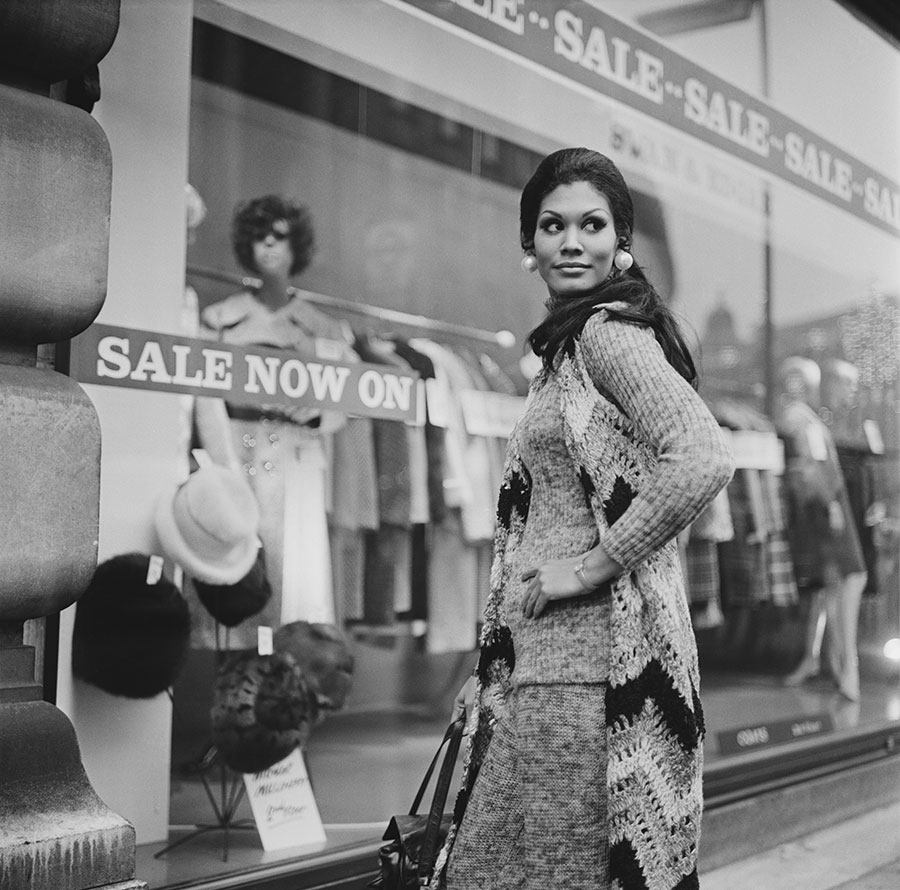

By the end of the night, 22-year-old Jennifer Hosten, who hailed from the tiny island of Grenada, took the crown despite 25-to-1 odds from British bookies. Floating across the stage in a gorgeous gold crocheted evening dress, she blew the judges away with her grace and her intelligent answers to the usual inane pageant questions.

Although Jamaica’s Carole Joan Crawford made history in 1963 as the first woman from the Caribbean to win Miss World, Hosten made history as the first woman of colour to earn the title. Pearl Jansen, the Black contestant who entered as Miss Africa South, was first runner-up.

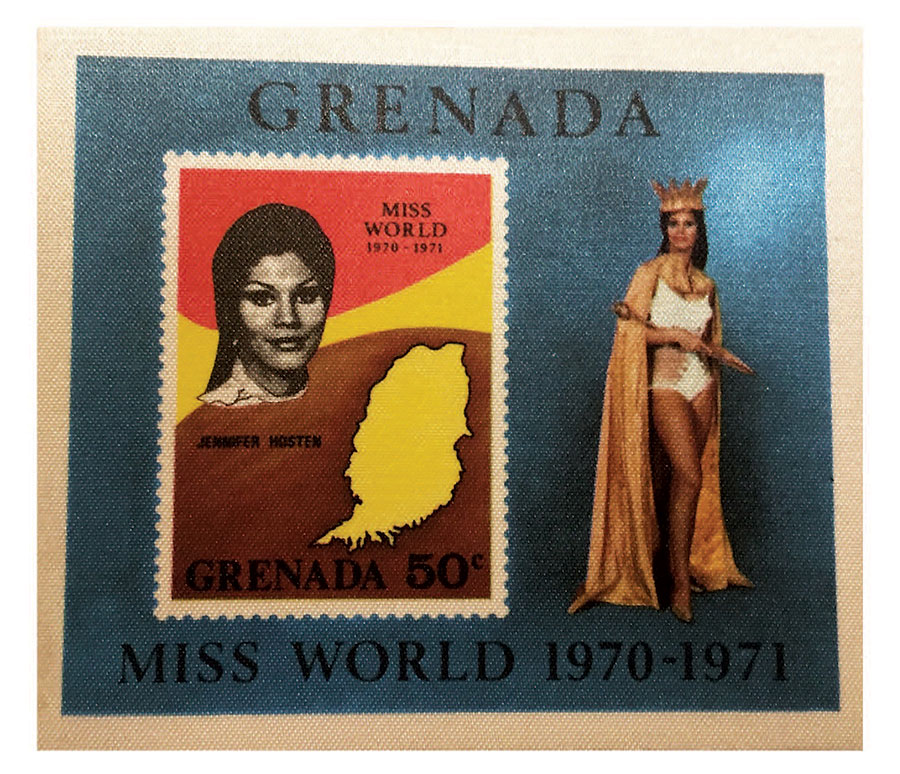

The biggest calypso star in the world, Grenada’s Mighty Sparrow, wrote a song in her honour called “Cousin Jennifer.” It called her a number of magical adjectives, including magnificent, glorious, captivating, glamorous, elegant and charming. Her image even graced a Grenadian stamp.

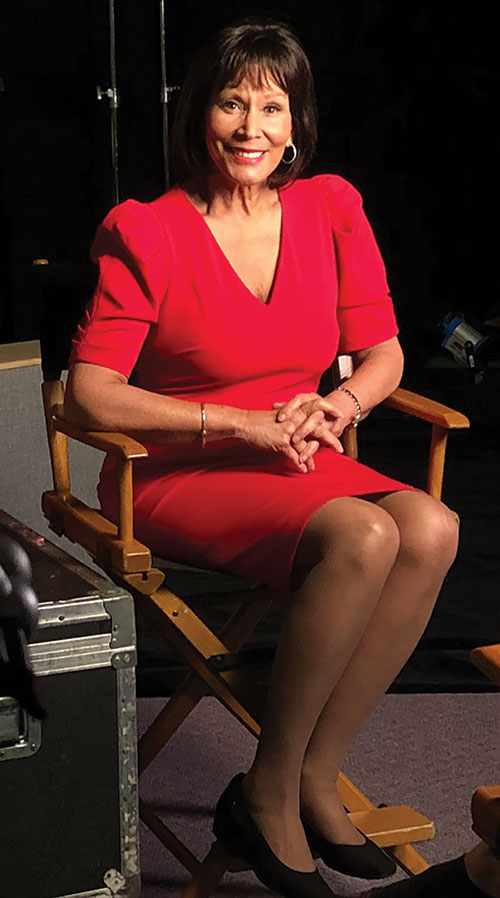

“I was also told that people on the Isle of Spice had danced in the streets to steel bands, carnival-style, and that upon my return to Grenada, a public holiday would be declared,” Hosten, 72, writes in her new memoir, Miss World 1970, which was published by Toronto’s Sutherland House Books on May 12. In a recent interview at her home in Oakville, Ont., she tells me that, because she was “darker than previous Miss Worlds, I had to venture out to the shops in a wig and dark glasses” to avoid recognition in London.

The more I researched Hosten ahead of our meeting, the more curious I was to meet the former beauty contestant who shares a Caribbean heritage with me, as my family hails from Barbados. Reading the book, I felt a connection to her propriety and the spoken and unspoken expected behaviour known to most Wes’ Indians of a certain class and a certain generation. Speak when spoken to, don’t air your dirty laundry and remember we always have to work twice as hard to get half as far. Our mutual Caribbean upbringing aided us in the chameleon-like behaviour known as code-switching, which allows us to navigate both cultures. It has served Hosten well.

Nearly 50 years after her historic pageant win, we gather on a wintery morning in her well-appointed condominium in Oakville, an upscale bedroom community 40 kilometres west of Toronto. The crackling fireplace, a steaming cup of coffee, comfy chairs with bold, floral cushions harkening back to the Caribbean make for a cosy backdrop for the conversation. I watch Hosten, holding my advance copy of her book, and see many emotions cross her face as she sees it for the first time.

When I ask how the book came about, Hosten recalls being asked to keep a diary by Trinidadian journalist David Rennick. “He said, ‘Promise me you’ll keep a diary’ – and I did. I didn’t write every day but I kept it up.” The tattered, mildewed journal that had been stored away for 40-plus years is the basis of her rich memoir, chronicling the events surrounding the fateful night that changed her life.

It is newly immortalized in Misbehaviour, a movie released March 13 in the U.K. starring Keira Knightley as the protest ringleader Sally Alexander and Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Hosten. I first noticed Mbatha-Raw in Belle, which played the film festival circuit in 2013, but she has also appeared in the British TV series Dr. Who and plays the talent booker in Apple TV’s The Morning Show, starring Jennifer Aniston.

In preparation for the role, Mbatha-Raw reached out to Hosten and arranged to meet her in Grenada, the island where it all began. Hosten brought her daughter, Sophia Craig-Massey, while Mbatha-Raw brought her mom. The four generations of double daters explored the island, while Mbatha-Raw absorbed the many facets of Hosten. “I was keen to capture Jennifer’s pragmatic and centred intelligence in my portrayal of her,” the actress writes in the foreword to Miss World 1970. That included learning the lilt of the Grenadian accent, which Hosten helped by recording her mother reading a poem for Mbatha-Raw to refer to back in London.

In fact, Hosten loaned the gold evening dress she handpicked for the 1970 competition – which she called her “secret weapon” in the book – to Mbatha-Raw for the film.

“Gugu was meant to play me in so many ways,” Hosten says. “Gugu was thrilled to wear my dress, and it fit her perfectly – they didn’t have to adjust it.”

After spending four magical days in Grenada to “discover more details” and to “honour her spirit in the role,” Mbatha-Raw leaves with the impression that Hosten was and still is a force. “Before Beyoncé, before Rihanna, before Zendaya, there was Jennifer Hosten, a true trailblazer, an icon to inspire the next generation to know that they are seen and valued on the world stage,” she writes in the book’s foreword.

Traditionally, when someone wins a prize or a contest, the winner is allowed some time to bask in the glory and celebrate. Sadly, Hosten wasn’t allowed to luxuriate in her triumph, writing that she “awoke to a nightmare.” News reports focused on the fact she was “mixed race or, in their eyes, black.” One suggested there was “a conspiracy by black members of the judging panel,” which included Grenadian Prime Minister Eric Gairy. His participation was questioned back home by the Grenadian opposition party, which called for an inquiry into the pageant’s result. It goes to prove that her win was politicized in many ways.

Hosten recounts the backlash in a chapter titled “Rigging, Racism and Rioting,” where she writes about comments from fellow contestants such as Miss Ireland. “Miss Grenada didn’t even have a nice figure. There is something wrong with the system.” And from Miss Switzerland, the land known for its neutrality: “It was all political. I have nothing against coloured girls, but how Miss Grenada could win I don’t know.” Judge Joan Collins, who went on to star as a nymphomaniac in the film version of her sister Jackie’s novel The Stud, bought into a classic racialized stereotype that hyper-sexualizes Black women and girls when she said: “Miss Grenada just wasn’t the most beautiful there. Her sex appeal bowled them over.” She dismissed Hosten as if she had nothing else to offer.

Hosten batted away the criticism, foreshadowing her future diplomatic skills, and considered the win an accomplishment. “Over time, I came to the view that the feminist protests around Miss World 1970 had contributed to my victory,” she writes. “Not in large part but somewhat because they were insisting that it was all about beauty and only beauty could win. The judges chose someone who had made a deliberate effort to present herself as a person and performed well in every aspect of the contest.” It was what she and her supportive elder sister, Pommie, called “the package.”

Even with her British-based education and proper Wes’ Indian background, Hosten had no sense of the hotbed of social tensions that awaited when she arrived in London with her sister.

“I didn’t realize I was competing at the height of this period,” she muses during the interview, “that the 1970 contest would be the launch of the women’s movement.”

The Caribbean pageant culture is far less fraught as it is centred around the idea of a carnival queen, who is judged on the creativity of a costume, rather than mere looks. Hosten had entered two previous carnival competitions, which she lost. She went on to work in broadcasting in Grenada, which led to a year of training at the BBC in London. Because her mother had been born in Canada, after that ended she grabbed an opportunity to move to Montreal to take on a “low-level job in the bowels of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation,” as she describes it in the book. “I had always been romantic about Canada because it was my mother’s homeland.” But the job was “drudgery,” and after she was sexually assaulted by an unnamed CBC actor who tore her blouse on a date, she jumped at the chance to work for British West Indian Airways.

“It was not a difficult decision: a chance to see the world was much more appealing than another winter in Montreal,” she writes. “It was a glorious time to be a flight attendant,” with a travel allowance that allowed her to shop in New York City and bank her pay. Working in first class, she met actor Peter Ustinov and Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. At that time in the Caribbean, it was a glamorous gig. And it was a chance photograph with Miss Guyana on a flight to Trinidad, published in all the Caribbean papers, that led to an offer to enter her first Miss Grenada contest. The prize? A trip to London for Miss World.

Moving into an international beauty competition, she expected a heightened requirement of brains as well as beauty. So she was surprised when the feminists who vehemently opposed the Miss World pageant didn’t reach out to the competitors. “It struck me that the women’s movement had used the beauty contest in much the same way as contestants were using the beauty contests as a platform or springboard,” she says. Ouch, I say!

Hosten is too circumspect to say whether she was annoyed that her historic moment was overshadowed by a women’s movement that was imposing its version of feminism on the Miss World contestants, as if to say its members knew what was best for all women. Ten years ago, BBC Radio 4 invited key participants of the Miss World 1970 program for an on-air reunion. Historically linked by the ruckus, media, and arrests of that night, Hosten met activists Sally Alexander and Jo Robinson for the first time.

They were unapologetic and stood by their actions of 40 years ago. Face to face, both sides agreed on the basic tenets of women’s rights. However, they still weren’t aligned on how and when to fight. “I still found them reactionary,” Hosten writes. When the unwitting male host made the mistake of saying “ladies” instead of “women,” he was promptly chastised by Armstrong and Robinson, “which to me is nitpicking. There are far more important issues facing women,” Hosten says in our interview. Indeed, they are. Consider the recent U.S. primaries, where six women started off in the race – including California senator Kamala Harris, who is of Jamaican and South Asian descent – and by election day, the country will choose one of two white, male septuagenarians. Imagine if Rihanna had been born a half-century earlier to remind white allies to be more sympathetic and inclusive and, in her words, simply “Pull up.”

When I ask about Hosten’s many careers, she leans forward as if the feminists of yesteryear are listening and says, “I took advantage of the opportunities put before me.” I was reminded of that as I read the book, travelling with Hosten as she fluidly switched from broadcaster to airline stewardess to Miss World, then from high commissioner for Grenada in Ottawa to a masters in political science at Carleton University to working for the Canadian International Development Agency, not to mention the decade she spent running a resort in Grenada called Jenny’s Place. Her final milestone was returning to school in Canada at 60 to become a psychotherapist and counsellor. On the way home, I stare at the striking photo of Hosten on the back cover of the book, accompanied by this quote: “You have to take advantage of what opportunities come your way. They’ll come in forms you would never imagine, and they’ll take you places you would never expect to be.”

In her wake, other women of colour have gone on to compete for Miss World and other major pageant crowns – turning the perception of objectification on its head and using them as platforms of empowerment. Growing up in Grenada, a country that was more “class conscious than colour conscious,” Hosten says being mixed race wasn’t an issue as the country was made up of citizens who were a mélange of the original Caribe Indian, descendants of Black slaves and the Scottish, Dutch and British settlers – just like her. But representation is complicated.

Just before interviewing Hosten, by chance I met Miss World 1976 Cindy Breakspeare at an arts fair in Jamaica. It was only after she left that I learned she was that Cindy Breakspeare – former lover of Bob Marley, the reggae superstar who is Jamaican royalty – and the mother of his ninth and youngest child, Damian Marley. Born in Toronto to a British-Jamaican father of multi-racial ancestry and a white Canadian mother of British origin, Breakspeare can pass for white.

It wasn’t until Breakspeare travelled the globe as Miss World that she realized race was more nuanced than in Jamaica, where she never felt like an outsider.

“When I went to Iceland, I realized I wasn’t white, and when I went to Nigeria, I wasn’t Black. They were expecting someone of darker complexion,” she told Toronto freelance journalist Ron Fanfair in a 2019 interview. “What that did, I think, was really highlight for me the uniqueness of the Jamaican experience and what it means to be Jamaican. It’s not a colour thing. It’s a cultural thing and, when you see the way Jamaica culture has taken over the world, to be Jamaican is the coolest thing.”

In 1984, when a light-skinned, blue-eyed, blond named Vanessa Williams broke another pageant barrier as the first African-American to be crowned Miss America, her win, like Hosten’s, was greeted with both joy and anger. Unsurprisingly, racism reared its head. Some of the backlash came from her own community, which saw her as an avatar for European, not Afro-centric, beauty standards. Williams was forced to resign her crown amid a scandal when sexual photos she had posed for years earlier were published in Penthouse magazine during her reign. Those who saw Williams’ win as progress took heart in the irony that her replacement, first runner-up Suzette Charles, was a Black woman and, this time, of West Indian descent.

It’s not lost on me, despite my lack of interest in pageants, that by the end of 2019, five Black women of all hues and hair textures made headlines for winning the major top pageant titles: Miss Universe, Miss World, Miss America, Miss USA and Miss Teen USA. It is finally my bragging right in 2020 that Black women, who look like me, my family, my friends, my ancestors, are finally getting their due. The definition of beauty now includes us and is the new standard.

When I ask Hosten how her daughter would describe her, Hosten offers to call her. I decline, but she calls me later and says that Craig-Massey has declared she is resilient, ambitious and charming. Within moments of engaging with Hosten’s warm, twinkly eyes and taking in her restrained sophistication, I am ready to add my own adjectives: warm, funny, smart and interesting.

I walked into Hosten’s condo with preconceived notions of pageants, pageant life and the women who enter them. I walked out slightly besotted with Jennifer Hosten. She and the other brave women of that era – including my mom – left former colonies, little islands floating in the Caribbean, to rise above their stations. Collectively, these immigrant warrior women fought to attain more. Regardless of what profession they chose, they went on to achieve greatness in many fields. They garnered a sense of self, a sense of self-sufficiency, a sense of moving forward and, most importantly, upward – a trajectory that included being crowned Miss World.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2019 issue with the headline, “The Most Beautiful Girl In the World,” p. 44.

RELATED:

Black History Month: Trailblazing Black Models Who Broke Barriers

Why Willie O’Ree, NHL’s First Black Player, Is More Relevant Than Ever

A Legacy of Firsts: Remembering Diahann Carroll, Star of Stage and Screen Who Died at 84