Norman Jewison: From the Civil Rights Movement to Big Screen Classics, Celebrating the Enduring Legacy of One of Canada’s Greatest Filmmakers

Photo: Peter Bregg

Combining showmanship with art, integrity and a passion for social justice is a balancing act rarely achieved in Hollywood. No one did it quite like Norman Jewison. The legendary Canadian filmmaker, who died last Saturday at the age of 97, was a singular talent. And while maintaining a stubborn independence from his studio bosses over the arc of a career spanning more than half a century, he was possessed by a singular sense of mission.

“Feature films are the literature of our generation,” he told me back in 1988 – a line he would repeat like a mantra over the years. At the time, Jewison was heading to the Academy Awards, riding a triumphant comeback with Moonstruck after a string of box-office misfires. This off-kilter romcom made a leading man of Nicholas Cage and reinvented Cher, who would win one of the movie’s three Oscars. Moonstruck would be Jewison’s last hit.

But by then, his legacy as one of the most significant Hollywood directors of his or any generation was firmly established. And the legacy didn’t end there. That same year, 1988, in his hometown of Toronto, he founded the institute that would evolve into the Canadian Film Centre (CFC), a professional development hub that would incubate new generations of Canadian directors, actors, screenwriters and producers.

In the early years of the film festival that became TIFF, he would host its annual barbecue at his farm in the Caledon Hills, north of Toronto, and later on the sprawling lawns of the CFC campus. He brought A-list talent to the party but never played the Hollywood big shot. A genial host for generations of emerging filmmakers, he was just Norman.

Jewison was occasionally criticized by his compatriots for not making Canadian films. (The closest he came was 1985’s Agnes of God, which was set in Montreal with largely local Canadian crew and American stars Jane Fonda, Meg Tilly and Anne Bancroft.) But for someone trying to forge a career in the 1960s, Canada had no film industry to speak of outside Quebec. By creating and promoting the Film Centre, and mentoring a new wave of daring Canadian directors – such as Bruce McDonald (Highway 61), who launched his career working out of Jewison’s Toronto office – Jewison gave more than his share back to his homeland. Without ever making a Canadian film, he managed to become the godfather of Canadian cinema.

Younger homegrown directors would migrate to Hollywood and surpass him at the box-office with studio blockbusters: Ivan Reitman (Ghostbusters), James Cameron (Terminator, Avatar), and Denis Villeneuve (Dune). But none would create a body of work with the diversity and depth of the movies that Jewison made in the first three decades of his career.

Preceding the cohort of film-schooled American directors who transformed Hollywood in the 1970s – Scorsese, Spielberg, Coppola, Lucas – he broke fresh ground with a string of stylish, provocative and politically trenchant hits in the 1960s. By then, he had carved out his independence from the studio system to become one of the few directors allowed to make the final cut of their work. After making his name with The Cincinnati Kid (1965), a deft gambling drama starring Steve McQueen, and his Cold War satire The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966), in 1967 he changed gears again and made the most memorable and significant work of his career: In the Heat of Night.

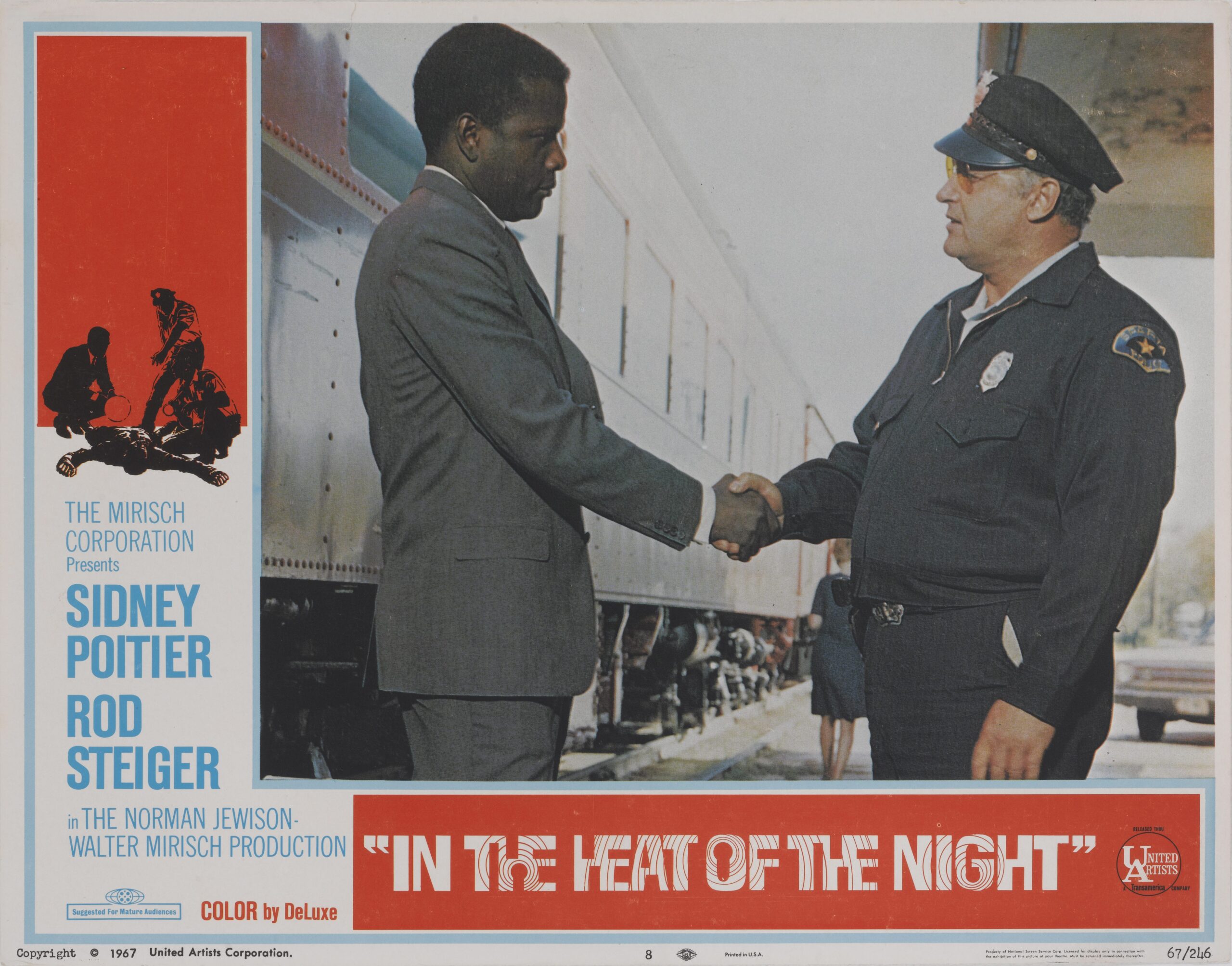

The story of a redneck sheriff in a Mississippi town (Rod Steiger) squaring off against a Black police detective from Philadelphia (Sidney Poitier), this powerful drama, which won five Academy Awards, hit a raw nerve in America at the height of the civil rights movement.

“It was the first film I can think of in which the Black man hit the white man,” Steiger told me in an interview 20 years later. “Sidney Poitier and I used to sneak into theatres just to watch the audience’s reaction.”

Steiger won Best Actor and the movie won Best Picture. But Jewison lost Best Director to The Graduate’s Mike Nichols, perhaps the only major Hollywood director with a stylistic palette as wildly eclectic as his own. Nominated seven times over the course of his career, Jewison never did win an Academy Award, though his movies and their actors won a dozen out of 46 nominations. And the Academy confirmed his status in the pantheon with the lifetime achievement honour, the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award.

Like so many visionaries who built America’s Dream Machine, Jewison came from elsewhere. And from extravagant musicals to gritty social justice dramas, the creative inflection that he brought to American cinema was a distinctly Canadian sensibility – the perspective of an outsider playing their game while questioning the rules.

His passion for social justice went back to his childhood growing up in Toronto’s Beaches neighbourhood, where he experienced anti-Semitism because of his Jewish-sounding name, although he wasn’t Jewish. His distaste for bigotry was compounded by a hitchhiking trip through the American South as a young man. Cutting his teeth as a director in early days of television, he entered showbiz in the right place at the right time.

In 1960, Jewison directed a Harry Belafonte network special that marked the first American TV show devoted to Black talent – the broadcast opened with white chains dangling from the stage set, and network stations in the southern states soon started cutting their feeds. He marched with Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy in civil right protests and became close to Kennedy. He loved to relate an anecdote about a crucial conversation he had with Kennedy while he was filming In The Heat of the Night.

“Bobby was telling me it’s an important film. He said, ‘Norman, the timing’s right,'” he told me once, fondly mimicking the Kennedy accent.

As it turned out, the timing was too close for comfort. The movie won its Oscars at a ceremony delayed two days due to King’s assassination. And Kennedy was murdered two months later.

The disintegration of America persuaded Jewison to return his green card and move to Europe. (Later he would end up dividing his life between homes in Toronto and Malibu, Calif.) After scoring hits in the early ’70s with a one-two punch of Judeo-Christian musicals in Fiddler on the Roof (1971) and Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), he continued to stir the pot, satirizing the American legal system in . . .And Justice for All (1979), starring Al Pacino, and marshalling a Black cast for A Soldier’s Story (1984), a potent drama about racism on a Louisiana army base.

In the 1990s, as a white director drawn to dramas of Black injustice, Jewison ran into resistance from Black filmmakers. He had planned to make a bio-pic about Malcolm X, but walked away from it after objections from Spike Lee, who ended up directing it. But with the penultimate film of his career, The Hurricane (1999), Jewison dramatized the true story of African-American boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, who had settled in Toronto after being imprisoned in the U.S. for 20 years on murder charges that were later dismissed. The movie, which won critical acclaim and an Oscar nomination for star Denzel Washington, was Jewison’s last hurrah.

By end of the ’90s, his golden ticket was running out, even though he never stopped trying to get movies made. When asked when he’d stop, he liked to quote director William Wyler – “when the legs give out.”

As Jewison’s Los Angeles agent Jay Auerbach once told the late Globe & Mail film critic Jay Scott, “He wants to do movies no one wants to finance. Then there’s the politics. I wish Norman would shut up about American politics – he’s known as a Canadian here, an outsider. All the anti-American statements he made in the 1960s really hurt him in this town.” So much for the alleged liberalism of the Hollywood elite.

The kind of pictures that Jewison liked to make – movies for grown-ups with a satirical edge, political gravitas and intelligent dialogue – had fallen out fashion in a Hollywood that was busy chasing space ships. As he told me in 1988, “I can’t direct spaceships.”

Jewison’s reputation as a filmmaker who dramatized social issues could overshadow his virtuosity as a savvy director who knew how to draw inspired performances from actors. “He’s very much an actor’s director,” Cher told me when I interviewed her about Moonstruck for Maclean’s in 1988. “He figures out what everyone needs and what they need him to be. He’s so sharp. You think that things are off the cuff, but he’s very devious. I don’t think there’s one moment when he isn’t planning what’s going on.” On the set, she added, he could be charming or crusty, funny or fatherly. “Norman is a showman. He’s an actor himself. He loves telling stories and loves being the centre of attention.”

For a final perspective on this Canadian showman who never felt completely at home in Hollywood, it’s worth giving the last word to Scott, an American draft dodger who made his name here as the most eloquent and erudite film critic (and champion of Canadian cinema) that this country has ever seen.

Scott, whose unconventional tastes didn’t prevent him from embracing a mainstream genius when he saw one, wrote that Jewison “minted a golden coin: American chutzpah on one side, Canadian civility on the other. In his films, he has used it to purchase a podium from which to teach Americans entertainingly something about themselves. In Canada, he is committed to spending it on a centre that he hopes will confirm for a new generation of Canadians who want to earn the same coin that there can be – and must be and will be – a here here.”