A Flash In the Pan: How the Digital Era Gave Rise to Global Food Trends

What we eat is being shaped at breakneck speed by diverse food trends that come and go in the blink of #foodstagram. Photo: Peden & Munk/Getty Images

We hear the hiss of coriander seeds. The fenugreek snaps.

Found within the vestiges of YouTube is a priceless moment from the early 1990s that almost acts as a preview of food-world convergence to come: Julia Child, in the amber glow of later-in-life fame, standing beside guest cook Madhur Jaffrey, known far and wide as, well, the Indian Julia Child.

Watching the extra-tall, ever-flutey Julia coo and look slightly befuddled as a rather sparrow-like and quintessentially regal Jaffrey gives the drill on preparing Shrimp in Spicy Coconut Sauce, we are privy to not only a masterful moment in odd coupledom — think the kitchen equivalent of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Danny DeVito — but a winnowing of culinary orthodoxy and the coming of a much larger, way more inclusive food landscape.

“She was totally puzzled,” Jaffrey told me years later when I interviewed her in Toronto. She fully appreciated the platform Child had given her but, at the same time, italicized the extent to which the gourmet lingua franca for Child — and the cognoscenti at large — leaned exhaustively toward French cuisine. Indeed, Jaffrey is the first to tell you that when she organized her first public cooking class, after she’d penned her first book decades ago, she got few takers. Only after legendary gourmand James Beard offered to host it at his house and invite some friends was there a trickle.

Some 30 cookbooks and a plethora of TV stints later, Jaffrey’s influence is manifest, particularly in the U.K., where famed British restaurant critic A.A. Gill once pronounced matter-of-factly, “Curry is the national dish.” The Indian cook’s legacy is right there in the samosas you might find at your book club gathering or office mixer, as well as on many a mainstream menu, like when Daniel Boulud pushes a signature dish of Quail with Garam Masala. Or, heck, even the turmeric lattes that are currently all the coffee-shop rage.

Stumbling upon that particular YouTube video recently, in the context of our modern food sphere — a vast vortex that zooms everywhere from poke bowls to za’atar crackers, Beyond Meat burgers to avocado everything, quinoa galore to cauliflower-crust pizza, kimchi to kombucha, not to mention a conga line of dairy substitutes like oat milk — it also helped to reinforce something else for me: how small, even quaint, the landscape of food media once used to be. And how, of all the dramatic changes that the last two decades have brought us, the glaring macro one is the sheer scale and velocity around the conversation about food.

Like so much of media now, where everyone is essentially their own broadcaster — and their own broadsheet, when you think about it — the food conversation once depended on an agenda set by a few players, like Child and Jaffrey. The feedback loop was a narrow one; the gatekeepers, minuscule.

What we are seeing and eating today is held up by a large tent encompassing the rise of 24-7 food programming, the one-name familiarity we have with pros like Jamie and Nigella and Rachael and Bobby and Ina, plus the long runway that is Top Chef, which releases newly minted celebrity chefs into the restaurant world every year. We are, after all, only one generation into the round-the-clock Food Network. Add to that a medley of other mainstays like Chopped and Master Chef, a torrent of more auteur-like shows churned out by the streamers (think Chef’s Table on Netflix or Salt Fat Acid Heat courtesy of Samin Nosrat), and a handful of influential magazines like Saveur and Bon Appetit still crawling along. Even more pressingly, there is an endless, ravenous online ecosystem comprised of food blogs and Facebook watch-and-stir tutorials (see the vast cooking school that is YouTube), not to mention inspiration run amok on Pinterest (the communal fridge door?), a bevy of review sites (hello, Yelp) and the almighty #foodstagram.

All too obvious, as David Sax, author of the comprehensive book Tastemakers, points out, is this: “Every single minute of our dining world is being chronicled, photographed, critiqued and commented on in a relentless cycle that has no switch.” It’s a trickle-down (or trickle-sideways) effect that has even infiltrated two recently reissued classics, How to Cook Everything and Joy of Cooking, in the way that they piggyback on online trends. The ninth edition of Joy is a fourth-generation riff on a book that St. Louis housewife Irma Rombauer self-published in 1931 — one of the original “influencers,” if you will.

Remember the old adage, we eat with our eyes? The extent to which this is truer than any other time in history is summed up by what star Chicago chef Grant Achatz has said of digital photography being the thing that “rocket-ships the speed in which trends not only come but go.”

Where, in a previous age, what was known as nouvelle cuisine literally took years to book passage across the Atlantic, these days, everything is available to everyone all the time. Consider the singular phenomenon known as the molten chocolate cake, created in 1987. It started in one city, was written up in magazines, noticed by critics, then copied on menus in various world capitals before strolling its way onto mainstream menus like Applebee’s.

Today, however, it is not so much farm to table as it is screen to stove.

Consider, too, that doughnut-croissant hybrid known as the Cronut, arguably the first big social media-enabled trend, rising up in May of 2013. It took less than two weeks for copycats to appear the world over. “Whereas cupcakes took one or two years to move out from the Magnolia kitchen into New York bakeries … and almost a decade to establish the cupcake trend internationally,” as Sax explained in Tastemakers, “the Cronut emerged from (New York baker) Dominique Ansel’s kitchen and emerged directly into the world of imitators, hybrids and inspired pastry creations popping up as far afield as San Diego, London, Singapore and even Caracas.” In South Korea, the Dunkin Donuts chain had already mass-produced what they dubbed a New York Pie Donut by late July.

To further zero in on the Zeitgeist, give thought to the analogy that the popularization of chef culture is as big a bolt to the food world as the invention of recorded music was for musicians. Before the phonograph, bands and singers could only build their audience on stage, one show at a time. Chefs today, unconstrained by their physical kitchens, are no different, able to create and shape food trends quicker and more expansively.

It is analogous to the swift dance between haute couture and fast fashion. In a time where everything moves with blitzkrieg speed — where Anna Wintour sees what is coming down the catwalks at the same time as that enterprising young blogger in South Korea because everything is live-streamed and uploaded in a jiffy — there is barely any gestation period for trends. That’s why all the fashionable people in London look just like all the fashionable people in Beirut who look just like all the fashionable people in L.A.

Ditto what we see on our plates, and why many a keen observer has noticed a creeping sameness to everything from the flatware in restaurants the world over to the wallpaper on their walls and the fonts on their menus. Trends have always had a propensity for metabolizing, of course, but it is the near real-time speed that distinguishes our moment.

“I did not know what a pilot was!” Emeril Lagasse laughed, when I talked to him last year at a food festival, as he recalled his initial audition at the nascent Food Network. Largely considered the first big celebrity to come out of that brand-new star-making factory (making the word BAM! a thing, along the way), he also reflected on how we got from that innocent time to one where many “chefs actually cook for Instagram,” often acting as stylist to their diners’ photographic ambitions. And restaurants, at large, are now reliant on the free marketing good pics can create.

Ruth Reichl, the beloved author and ex-editor of Gourmet, was even blunter in a separate interview when she said: “There’s no question that Instagram and other platforms like it are producing food that looks good in a snapshot rather than food that tastes good.”

Chalk it up to commodity fetishism. Or social currency. Or a gung-ho combination of both. “Food thrives on social networks because of its easy, graphic appeal and pan-demographic interest – we all have to eat, right?” is how Amanda Mull, doing a deep dive on the website Eater, once summed up the phenomenon.

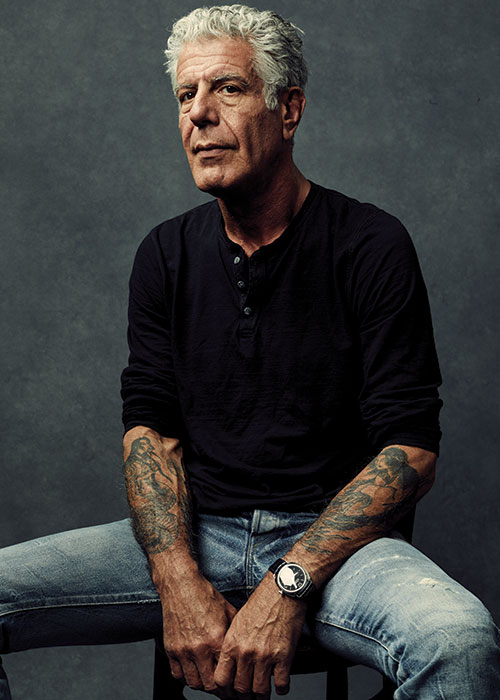

The extent to which food entered the mainstream cultural conversation was exemplified by the mass outpouring of grief accompanying the news of Anthony Bourdain’s suicide in 2019. Sometimes referred to as “the Indiana Jones of the food world,” the extra-tall Bourdain, with his chatty bar-stool persona, had become TV’s most powerful, if unlikely, “foreign correspondent.” He was essentially using food as a way to report everywhere from Tehran to Tokyo.

All of which has often made me wonder: how would someone like Julia Child have manoeuvred in the #foodstagram climate? I got as good an insight as I am likely to get when I talked to her nephew Alex Prud’homme, the collaborator on her memoir My Life in France. She was “always evolving … adjusting on the fly,” he once told me. And while Child is often touted as being a late bloomer (she didn’t pick up a ladle until she was in her late 30s), he believes that the woman whose very kitchen now sits in the Smithsonian had a life-long ability to “rebrand.”

“She didn’t sit back and have regrets. It was ‘Let’s move on,’” he continued. “She was an early adopter person … was on email early … and she liked to share her enthusiasm.”

So, like, yeah: Julia would probably be hash-tagging with the best of ’em had she lived to see this brave new foodie world.

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2019/20 issue with the headline, “A Flash In the Pan,” p. 39.

RELATED: