Supermodel Beverly Johnson, 67, Engaged to Wall Street Financier Boyfriend, 70

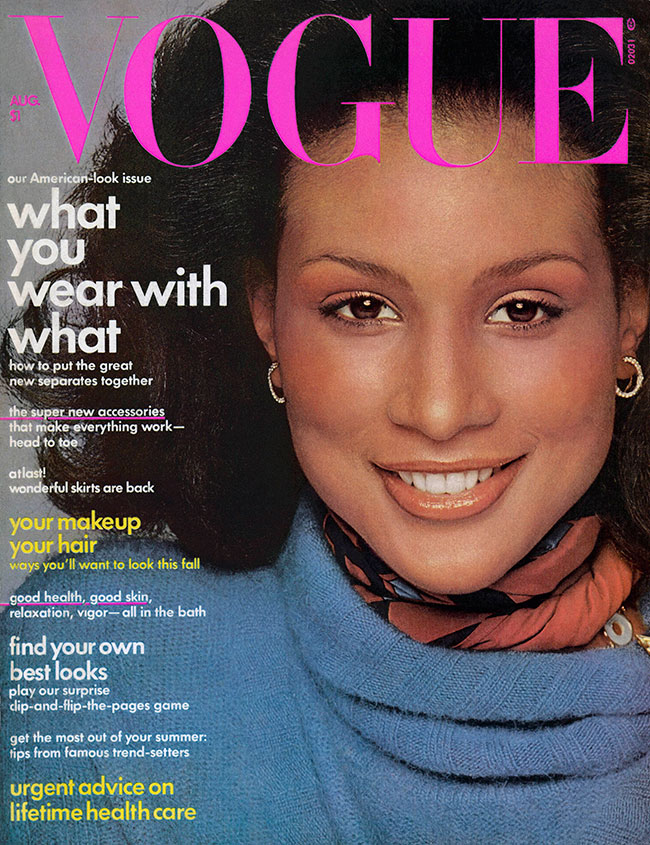

Beverly Johnson in 1977, at the beginning of her 50-year fight for inclusion and equal pay for African-American models. Photo: Gems/Redferns

It took two marriages and a string of relationships with bold-faced names like actor Chris Noth, boxer Mike Tyson and tennis star Arthur Ashe to find The One, but supermodel, actress and businesswoman Beverly Johnson, 67, is engaged to Wall Street financier Brian Maillian, 70.

“This is the first time I’ve dated someone close to my age,” she tells People magazine. “We know the same songs and we’ve lived through a lot of the same things. … Just finding the love of my life at this point in my life has been amazing.”

Johnson, a fashion icon, was the first African-American model to appear on the cover of American Vogue in 1974, at the same time Maillian was breaking barriers for African Americans in the banking world.

“As I was breaking boundaries in the fashion industry, he was doing the same on Wall Street.”

Johnson had been dating Maillian, chairman and CEO of his own investment banking firm, Whitestone Capital Group, for nine years when he unexpectedly popped the question at a family gathering in Palm Springs, Calif., after her sister, Sheilah, asked when he was going to propose.

“I have asked her to marry me,” Johnson recalls him saying. “And she said, ‘No.’ Besides that — I don’t have a ring.” With that, Maillian’s 88-year-old mother Ruby took off her ring and passed it down the dinner table to her son, who got down on one knee then and there.

“I was sobbing uncontrollably and he said, ‘Will you marry me?’ and I said yes!” says Johnson, who divorced real-estate agent Billy Potter in 1974 and music producer Danny Sims, the father of her 41-year-old daughter Anansa, in 1979. “”I was like how the heck did that happen? I was saying I’m never going to get married again.”

Maillian took her to a jewellery store to look at rings, but Johnson said she wanted to buy a house instead. Johnson, an avid golfer, and her fiancé live in an exclusive gated community in Rancho Mirage, Calif., across from the Thunderbird Country Club.

In 2014, when she turned 60, Johnson told AARP magazine: “the intimate feelings you had when you were younger can still be had if you’re interested in love. My partner, Brian Maillian, is about my age; that’s unusual because I usually dated younger men. It’s wonderful to have a companion at the same place in life as me.”

Making History

Johnson, who was born in Buffalo, New York, chronicled her early years in her 2015 memoir, The Face That Changed It All, which documented her meteoric modelling career, as well as unwanted sexual advances that began when she was 12, her former cocaine addiction, battles with bulimia and anorexia, a prolonged custody battle over her daughter and a scary 1986 encounter with actor Bill Cosby, who drugged her coffee but did not assault her. Cosby, 83, was jailed in 2018 for drugging and sexually assaulting Andrea Constad amid allegations of similar abuse from 50 other women.

Johnson’s 1974 American Vogue cover kicked off a mega-career that resulted in more than 500 magazine cover shoots.

That appearance, she writes in her memoir, “left an enduring mark on the country, its view of beauty, and the meaning of beauty for decades to come.”

In an excerpt from the book, Johnson describes meeting Liza Minnelli at a New York party thrown by designer Halston, where Elizabeth Taylor saw her ogling a massive ring, which she took off, tossed at Johnson and walked away.

She also describes how the only other Black woman at the party, model Pat Cleveland, had stripped naked and was asking people what they thought of her heart-shaped pubic hair. Johnson felt Cleveland had become “the show,” and had a hard time with the scene, given all the work civil rights activists had done to fight for equality.

“There were so many who had marched and sacrificed their lives so that I could have a place in the mainstream world of fashion and even attend that party that night,” she writes. “Maybe Pat felt the same but just had a very odd way of showing it.

The Beverly Johnson Rule

Johnson expanded on the racism she faced in the fashion world in a June opinion piece for The Washington Post, where she says she has been “fighting for inclusion and equal pay” for 50 years.

That 1974 cover was meant “to usher in a current of change.” But after George Floyd’s death on May 25 at the hands of four Minneapolis, Minn., police officers, “stories about discrimination in the fashion industry and at Vogue, in particular, have come under the spotlight.”

She recounts how she and other Black models, who were paid less than their white counterparts, fought for fair compensation, while she was reprimanded for requesting for Black makeup artists, hair stylists and photographers.

Johnson says the fashion industry, much like charges levelled at the music industry, “gouges” Black culture for inspiration and benefits from the profits. At the same time, it systematically inflicts harm, like Gucci’s 2018 “minstrel-themed” sweater and Burberry’s 2019 hoodie with a noose around the neck.

“When called out, these companies plead for forgiveness, waving promises and money around,” she writes. “Then it’s back to exclusion as usual, until the next brand “accidentally” repeats racial vulgarity. The racism management cycle then begins anew.”

Her solution, which she says on her Instagram account was proposed by Maillian, is the Beverly Johnson Rule. It takes its name from the NFL’s Rooney Rule, which mandates that people of colour get “meaningful” interviews for head coach and senior management roles to improve diversity.

It would require Code Nast — the publishing empire that includes Vogue, GQ, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair and Glamour and is led by international artistic director and American Vogue editor Anna Wintour — to meaningfully interview at least two black professionals “for influential positions.”

“This rule would be especially relevant to boards of directors, C-suite executives, top editorial positions and other influential roles. I also invite chief executives of companies in the fashion, beauty and media industries to adopt this rule.”

When Johnson landed that 1974 Vogue cover, the editor of Glamour magazine — who had given Johnson her first break in the 1970s — called her the “Jackie Robinson” of modelling.

“Forty-six years after my Vogue cover, I want to move from being an icon to an iconoclast and continue fighting the racism and exclusion that have been an ugly part of the beauty business for far too long,” Johnson writes.

RELATED:

At 50, Supermodel Naomi Campbell Matures From Bad Girl to Mentor and Activist

Black History Month: Trailblazing Black Models Who Broke Barriers

Iconic Model Pat Cleveland Diagnosed With Colon Cancer Just Days After Walking Paris Runway