Award-Winning Historian Ted Barris Uncovers the Truth About His Father’s War Experience

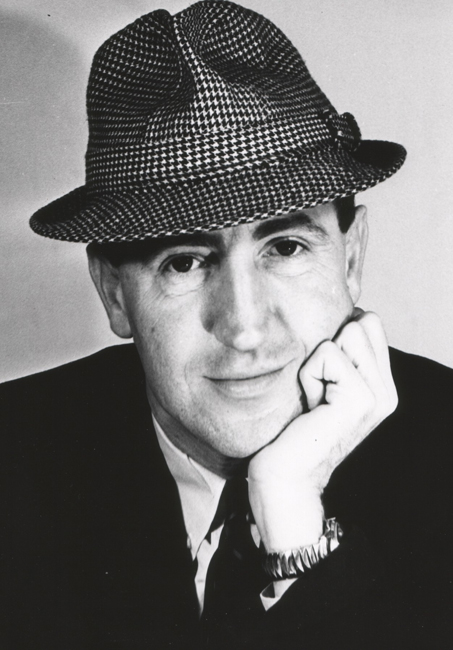

Alex Barris as a medic in the Second World War. Photo courtesy of Ted Barris

For more than five decades, journalist, broadcaster and bestselling author Ted Barris has chronicled the heroics of Canadian men and women at war, earning accolades including a Veterans’ Affairs Commendation and the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal. In his 19th book, Rush to Danger: Medics in the Line of Fire (2019), Barris recounts the front-line actions of medics, nurses and other medical personnel from 150 years of warfare. But in telling this tale Barris uncovered a much more personal war story, which he wrote about for Zoomer in 2019.

From the time I was an adolescent, I have chased my father’s war story. Especially after Alex Barris died — at age 81 — in 2004, my pursuit took me through family suitcases full of photographs and letters, to the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis to retrieve his military service papers, and on a personal trek across the German countryside retracing the path of his medical battalion in the U.S. Army during the Battle of the Bulge. In 2015, I found a list of active members of his army unit’s commemorative historical society. But I kept striking out. No answer. Not in service. Then, I dialled a number in Eatontown, New Jersey, and got an answer. “I’m looking for Tony Mellaci,” I said.

“You’ve found him,” the jovial voice answered.

“Mr. Mellaci, my name is Ted Barris and I’m wondering if you remember my father from the war. He was a medic…”

“Al Barris?” he interrupted.

“Yes…”

“The writer? From New York?”

“You knew him?” I asked, my voice shaking.

“Knew him? We served together in the 319th. And I’ve always wondered whatever happened to him. Is he still alive?”

News of my father’s death in 2004 was the only sad news we shared over the next hour. I was so excited that I’d found a witness to my dad’s other life as a sergeant medic (from 1942 to 1945) in the 319th Medical Battalion, serving Gen. George S. Patton’s 94th Infantry Division of the U.S. Third Army. On the phone, I peppered Mellaci with every question I could think of: How had they met? What was training like in Kansas and Mississippi? When did they make the transatlantic crossing on the troopship Queen Elizabeth? And certainly not least, what could he tell me about my father’s receiving a military citation during the Battle of the Bulge in Germany?

Mellaci, born in 1922, the same year as my father, sounded spry, upbeat and eager to answer all my questions. And because he knew I wanted something tangible about Dad, he recalled seeing their company captain, L.J. Sykora, present the Bronze Star to my father at Krefeld, Germany, just before the 94th pushed its way into Düsseldorf at the end of the war. But Mellaci kept coming back to an indelible image of my dad — taking notes, gathering stories and editing them for publication — almost as if the expenditure of all this creative energy might distract him from the trauma of the war.

“He jotted everything down,” Mellaci said. “He talked to everybody, always had jokes to tell. He kept us laughing. He was our battalion journalist.”

As I listened to the floodgates of Mellaci’s memory open wide with reminiscences, I knew we had to meet face-to-face. And soon! I sensed in Mellaci’s recollections I might learn a lot about my father’s attitude as a medic, about his personality in uniform, and specifically about the events in February 1945 at Campholz Woods, the battlefield where he was recognized for what the citation called “above the call of duty.” I gingerly suggested to Mellaci, if it were convenient, that I could travel there to see him.

“Come here to New Jersey? Sure. Anytime,” he said without hesitation. “And you don’t need a motel room. You can stay with us. You’re family!”

“You’re very kind…” I said, and I cried.

“Besides,” he concluded, “I have some of your father’s paperwork. You know, he wrote about us from training in Kansas all the way to Europe. Like in a battalion newsletter.”

“Never let them know the hell of your war”

The prospect of hearing my father’s voice in print grabbed me by the heartstrings. For years I had read and saved some of my father’s contemporary writing — when he was a newspaper columnist in the 1950s, a TV-variety and sitcom writer in the 1960s and ’70s, and as co-author with me on dozens of CBC radio scripts and two non-fiction books in the 1990s and early 2000s. But I had rarely, if ever, heard his writing voice before I came into his life. Suddenly, one of his affable old war buddies, who, like Dad, had left everything about the war behind when he returned to civilian life in the States — in Mellaci’s case, to take over his father’s tavern in Rumson, New Jersey — seemed ready to give me a part of my dad I didn’t have, stories of his comrade on or near the front lines of combat in the winter of 1945. For me, it was a part of Tech/Sgt. Barris I yearned to know. For former Staff/Sgt. Mellaci, it was a series of mental snapshots of a fellow American, a guy he’d depended on and who’d depended on him, a medical battalion brother, and a guy Tony repeatedly referred to as, “Al the writer!”

Many will remember writer, broadcaster, author and media personality Alex Barris. My father was born and raised in New York, which is why he served in the U.S. Army during the war. In 1945, the army repatriated him to New York, where he tried desperately to land a job with the New York Times; he did, in the press room manhandling ink and newsprint. In 1948, the Globe and Mail offered him a reporting position, so he married my mom and the two moved to Toronto to start a new life, leaving behind the sewing machines of a family fur business, and any memories of that last frigid winter of the war, trying to save lives during the Battle of the Bulge.

Not until I was nearly 15 did I learn anything about my father’s war. On my final day of Grade 9 classes in 1964, the phys-ed teacher gave us a bat and ball and told us to kill time with some pick-up baseball. Not long into the game, the catcher and I ran into each other head-on chasing the same pop fly. The collision broke my nose, knocked out my front teeth and put me out cold for a couple of minutes. I spent several weeks recuperating in bed at home, where my father, working as a freelance writer, spent hours trying to distract me from my pain and self-pity. It wasn’t long before I popped the big one. “What did you do in the war, Dad?”

Never afraid to tell a good yarn, but in this case holding the power to choose what he would say and not say, my father used a ploy — a safety mechanism that many veterans of the Great War, the Second World War, the Korean War, and recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have used — to answer my question. Never tell the rough stories, the remembrances of destruction close by. Don’t revisit the deaths of comrades on the battlefield. Under no circumstances let loved ones see you break down and cry. Instead, protect them. Always recall the antics, the quirky tales, and maybe the odd near miss. But never let them know the hell of your war.

That’s what my father did. For several afternoons in a row, as I lay in bed recovering from my schoolyard wounds, Dad regaled me with just the war stories he knew would leave me laughing. I had a rough idea that he was a U.S. Army medical corpsman during the Second World War. I knew from some of the stories he’d told at parties and occasionally around the family dinner table that he’d endured military training camps from Kansas to Mississippi. He rose to the rank of sergeant. During one stint in the winter of 1943, he recalled accidentally waking the battalion commander an hour too early for roll call outside in a freezing Kansas pre-dawn. My father told me about army food — K-rations, or “shit on a shingle,” and coffee that tasted like mud. In the army, everybody hated the food, and the cooks hated everybody back. Nobody ever got any food he liked. So, from the moment he received his baloney sandwich ration, each morning after breakfast until noon, when they stopped to eat lunch, my father searched for anybody who hated the peanut butter sandwich ration as much as he hated his baloney sandwich ration. Only then could he eat lunch — two peanut butter sandwiches.

Of course, using his dodge-and-evade tactic, what my father failed to mention, in all of his wartime descriptions, in all of the anecdotes he shared with me during those days when I was curious and convalescing, was an incident at Campholz Woods, Germany, during the Battle of the Bulge in February 1945. I didn’t know about it, and as far as he was concerned, that’s the way it would stay. Toward the end of my recuperation in June of 1964, I asked my father one last question about his war.

“Were you awarded anything? A medal? Something?”

Presently my father retrieved a medal with five points on it, hanging from a short piece of striped ribbon. He made no fuss over it. He shrugged off any mention I made of his wartime bravery. He simply suggested that if I really cared about it I should put it away for safekeeping. So I tucked the medal into a dresser drawer and promptly forgot about it. While I’d managed to get an answer to the question “What did you do in the war, Dad?” it was, after all, the answer he’d chosen to give. He had gone only as far as he felt comfortable. The rest would be left to my imagination or, as in the case of what happened at Campholz Woods, up to me to find out on my own.

Into the Woods

I did try the official route. I wrote to the National Personnel Records Centre (NPRC) in St. Louis, Missouri. It’s kind of the Fort Knox of veterans’ vital service data in the United States. However, on July 12, 1973, its fail-safe system couldn’t prevent fire from racing through the sixth floor of the NPRC and 80 per cent of the records of U.S. Army personnel discharged between 1912 and 1945, went up in smoke. My father’s honourable discharge occurred in December of 1945. I waited patiently for six months and when I finally received the return package of my father’s records in the mail, the contents showed just how close his service history had come to incineration. The photocopies clearly indicated singe marks around the edges of his military records.

I learned one detail of my father’s entry to armed service, when he and Tony Mellaci first met at Camp Phillips, Kansas, late in 1942. The singed NPRC records showed that as a newly sworn-in member of the 319th Medical Battalion, he was admitted to the base hospital just before noon on Dec. 25, 1942, with a diagnosis of “pharyngitis catarrhal acute” and a temperature of 102 degrees. I learned later from Bill Wilson, a retired Canadian medic, that my father had entered hospital with a severe cold and fever, with a bacterial invasion of his chest, throat and sinuses.

“No Christmas pass to Salina for him,” I suggested in jest.

“It was more serious than you realize,” medic Wilson wrote. “It’s like strep pneumonia and hemophilus influenza … with a 21 per cent morality rate if not treated.”

My trip to visit Tony Mellaci at his home in New Jersey in 2015 filled important gaps in my understanding of Dad’s time in the service. Tony’s wife Sharon, their sons, and neighbours welcomed me, well, like family. And Tony and I spent hours in conversation — he trying to pull details from his memory of their time together as medics saving lives, and I trying not to leave any stone unturned. Among many bits of memorabilia that Mellaci extracted from his files were copies of the Weekly Dose, the four-page newsletter of the 319th Medical Battalion. Its staff of four, according the Tony, scoured the training facility for printable tips, tales and gossip. In particular, Mellaci drew my attention to an editorial by one of the Dose staff, Al Barris, who, with tongue planted firmly in cheek, extended sympathy to all battalion ambulance and truck drivers, suggesting they fly their imaginary flags at half-staff because “Henrietta” and her companions were no more. The powers that be at Camp Phillips had outlawed feminine names on vehicles in honour of girlfriends.

“Slowly but surely they’re taking all the sentiment out of the army,” Editor-in-chief Barris wrote. “Pretty soon they’ll have us using medical names for the litters (stretchers), and, who knows, some day we may hear of Sgt. Sulphadiazine, Cpl. Capillary, and Pvt. Pneumonia.”

Mellaci shook his head and chortled with every line his buddy the battalion journalist had to offer in print. But after the fun of remembering the good times, Tony also divulged what my father had never written about or described to anyone — his recollection of T/Sgt. Barris’s actions at Campholz Woods on Feb. 12, 1945. Mellaci shuddered when he remembered the cold and the objective in that mid-winter campaign to clear the Germans from the Saar-Moselle Triangle. The Germans had anti-tank trenches, dragon’s teeth concrete barriers, concealed pillboxes, booby traps and Schü anti-personnel mines. “The infantry didn’t know that,” he said. “That’s why we had so many casualties. Walked in and boom.”

Mellaci admitted as a medic that he had one advantage over my father. He was the staff sergeant in charge of 10 ambulances and 20 men. His job involved transferring wounded at first-aid stations into ambulances of the motor pool and transporting them to more intensive medical treatment farther behind the lines. He explained that my father worked on foot, managing the stretcher-bearer medics and ensuring that they retrieved the wounded and got them to any available shelter — the first-aid stations right behind the front lines of the battle area.

“That’s where our boys (stretcher bearers and medics) got hurt that one night,” Mellaci continued, “where your father lost track of those guys and then went (into the woods) looking for them.”

A month later, during a short rest at Krefeld, Germany, with the battle of Campholz Woods behind them, S/Sgt. Mellaci learned that my father’s action — safely retrieving the four medics from the woods — had earned him a military citation.

“Hey, Al’s got the Bronze Star,” he remembered telling others in the motor pool. “Al’s got the Bronze Star!”

Tony Mellaci’s kitchen in New Jersey went silent as he and I re-read Dad’s citation together: “On 12 February 1945, one litter squad failed to return after an operation … in Campholz Woods. Tech 4 Barris personally entered these woods, which were heavily sown with mines and booby traps, and located the members of this squad — two were wounded, the remaining two were disoriented. … He managed to extricate the squad and furthered their evacuation through medical channels.

“His total disregard for personal safety and his continual service to his organization over and above the call of his particular duties are in keeping with the highest of army traditions.”

Decades Later, a Remarkable Twist of Fate

Two years ago, a career decision not only altered my working pattern as a writer, but it also changed how I remember my father. More specifically, in 10 days during the fall of 2017, I learned more about my father’s thoughts, his service as a medic and the hell of Campholz Woods. An advertisement invited travellers to join a 94th Infantry Division anniversary tour through sites of the Battle of the Bulge. Though the tour catered principally to Americans, I knew I had to go. I alerted the community college where I’d taught journalism for nearly 20 years in Toronto that I would retire before the fall semester. On Oct. 6, instead of teaching news reporting at Centennial College, the tour I’d joined crossed into Germany, just inside a former Second World War zone known as the Saar-Moselle Triangle. In a village, not far from Campholz Woods, our young guide led us to the market square and described one of the first street battles that U.S. and German forces waged in the Allied counteroffensive to the German breakout (the Bulge) that winter. In answer to a question from our group, the guide told us civilians had been evacuated.

“Well, that’s not entirely true,” said someone standing behind me — a man on the tour I hadn’t met yet. He added, “Some of the civilians refused to leave.”

I introduced myself to this fellow traveller, Al Theobald, from San Diego, California. Intentionally, we fell behind the rest of the walking tour to get acquainted. He told me that he’d been born in this part of Germany right after the war. His mother, Maria Fox, did eventually vacate her home in the nearby village of Borg on Christmas Day, 1944. Remarkably, when she returned to the family farmhouse after Borg was liberated by the Americans that winter, Al said, she found the home intact, but full of medical supplies…

“Medical supplies?” I interrupted.

“Yes,” he continued. “Bandages, medicines, utensils. Our home had been used by the Americans as a first-aid station.”

I couldn’t get the next words out of my mouth fast enough. “And where is this place, Borg?”

“About a mile from Campholz Woods.”

I was nearly speechless. I had travelled over 6,000 kilometres from my home in Canada into a part of Germany I’d never seen before. On a flyer, attached to this American commemorative tour of the Battle of the Bulge, I’d hoped I might learn something about my father’s being a runner for his medical battalion near Campholz, at best maybe visit this place my father had never described to me, but where, as a U.S. Army medic, he’d apparently rescued four men in his platoon in February of 1945. All I had to go on was the paper citation. Until that moment, I’d never come so close to knowing what Dad might have faced there. I read Al Theobald the Bronze Star citation the U.S. Army had issued about my father’s “total disregard for his personal safety.”

“I’ve got goosebumps,” Theobald said.

A few hours later, Maria Fox’s son and I — my heart in my throat — walked through the bunkers, trenches, tank traps and dense woods of Campholz. In some ways, Theobald told me, things there seemed just the same as in those final months of the war. The woods were just as dense, their look just as innocuous, the land just as pastoral. But when my father’s medical battalion had rushed wounded from this battleground, it was during the coldest winter of the war. There was a foot of snow on the ground. And hidden there in Campholz lay some of the most lethal anti-personnel weapons of the war — Schü mines, trip-wired booby traps, anti-tank explosives, and dragon’s teeth (row-on-row concrete obstructions).

Eventually, Al Theobald took me to the village of Borg and the location of his parents’ former home, the farmhouse (now gone) that my father’s medical battalion had occupied that winter. It had been, in all probability, my father’s first-aid station during his service as a medic on the front lines in the Battle of the Bulge, the place to which he’d somehow carried or dragged four wounded and disoriented medics on Feb. 12, 1945.

“Now it’s my turn for goosebumps,” I told Al Theobald. And for the rest of our trip together I couldn’t thank him enough for the chance he’d given me to be where my father had served — in the fullest sense of the word — in the Second World War.

I spent as long as I could soaking up the sights, smells and sounds of Campholz Woods, Germany, that fall day. I didn’t think I’d ever come back. So, before Al Theobald returned me to the tour of American travellers, I walked alone from where the nearest road ends in front of the forest. I turned on my cellphone and recorded my thoughts.

“You walked here, Dad,” I said into the recorder. “Crossed this very ground, not in the fall (like me) but in the winter, through knee-deep snow. Not across a plowed farm field, but across a battlefield sown with Schü mines. Not in daylight, but in darkness!

“You had sent your medics out here to bring back the wounded from the woods. Now, you had to find them and guide them back yourself,” I continued through tears into my cellphone. “You were responsible for them. You had to bring as many back alive as possible. Why? How the hell did you do this?”

Pursuit of my father’s war story had brought me closer to T/Sgt. Barris’s wartime deeds than ever before. I still struggle with the “How?” and “Why?” of it.

RELATED:

War Historian Ted Barris on the Heroism of Military Medics and His New Book ‘Rush to Danger’

Podcast: Ted Barris on the Untold Heroics of Canadian Soldiers

Liberation75: How One Orange Tulip Tells 1.1 Million War Stories