“I’ve Done the Best I Could”: A Frank Talk With David Suzuki About the Environment

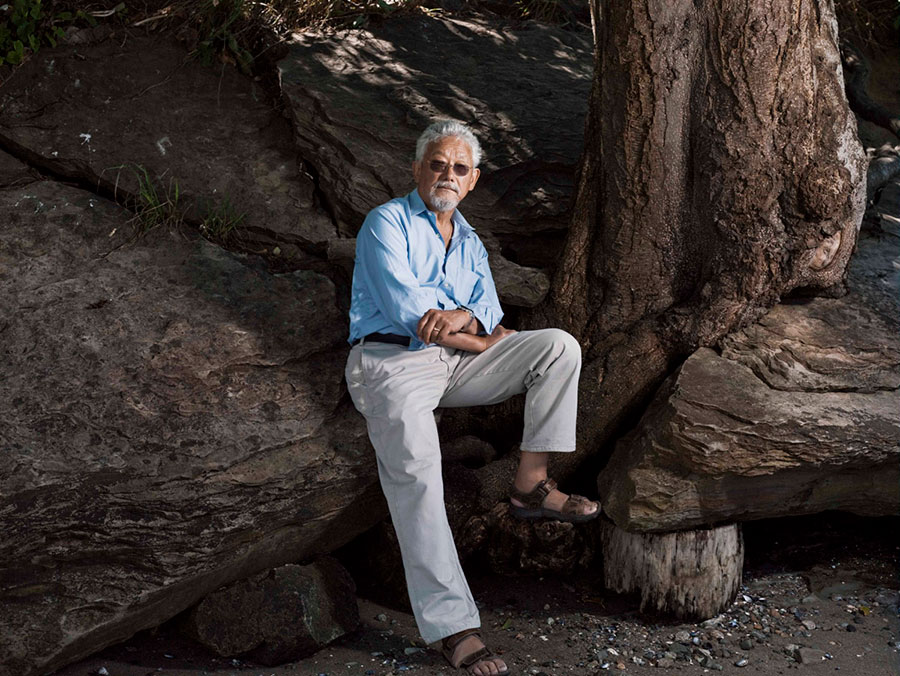

David Suzuki, 84, spoke to Zoomer about his legacy as an eco-warrior, why he feels his efforts fell short and how he intends to keep fighting. Photo: Malcolm Tweedy

David Suzuki wept.

It happened a few years back, as he held his twin granddaughters — who were around five or six months old at the time — in his arms.

“This has never happened to me before,” Suzuki, 84, explains over the phone from his Vancouver home. “I just suddenly realized that all of the things that I’m saying [about the environment] are coming true, and these kids don’t have a chance at living a full life.”

His wife and daughter hurried over to take the children and asked him what was wrong. “And then I just started to wail. I wailed with absolute grief of realizing what we’re doing. And it took me a while to get my composure back.”

At the time of our call — in February of this year — Suzuki was scheduled to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2020 Canadian Screen Awards for his work on the CBC science and documentary series The Nature of Things. He has hosted the show for 40 years, and it goes into its 60th season in September.

For many Canadians, Suzuki has always served as a calming and reassuring presence on the scientific front —brilliant, respected and fighting the good fight in the name of environmentalism. He even started his own non-profit environmental organization, the David Suzuki Foundation. As it turns out, however, Suzuki doesn’t feel that his decades of tireless work and environmental activism have paid off the way he’d have liked.

“People come up to me and thank me for what I’ve done, and I say ‘For what?’” he says. “I’ve done the best I could, but it hasn’t … We’re going right over the cliff. I don’t feel that it’s had the impact.”

Politics, Profits and Pipelines

Suzuki recalls starting on television in 1962 while at the University of Alberta and how “my whole involvement with the media is I felt that it was important to get the best information possible, get the best science out, so that people could make better decisions.”

And while he still feels that it’s an important role to maintain, the internet has given permission, in a sense, to anyone with any scientific belief to hold steadfast to it — regardless of how inaccurate it may be — because they can always find a website to validate it.

“You want to believe climate change is bullshit? Guess what — there are dozens of websites that tell you that,” he says, noting that he’s often approached by people who accuse him of lying about climate change to get money for his foundation. “And so the tragedy now is that we have information coming at us from every angle, but people aren’t critical about who’s putting that information out so they don’t have to change their minds.”

He also points a finger at the American Petroleum Institute which, he says, acknowledged the impact of burning coal, oil and gas on the environment in the 1960s but, by the late 1990s, questioned global warming and the human impact on it. When it comes to his anger over the situation, he doesn’t mince words.

“It just pisses me off that in the name of profit, the fossil fuel industry knew damn well that they were creating a problem that would be catastrophic and … they’ve just driven us right to the edge of the cliff.”

He references the Indigenous railway blockades, which were ongoing around the time of our interview, in protest of the Coastal GasLink Pipeline. Suzuki notes, “Suddenly Indigenous issues are coming to the forefront. But it’s still all about, ‘All of these Indians are keeping us from making money, they’re destroying the economy, blah, blah, blah.’ They’re not seeing what the real issue is. It’s about a relationship with Mother Earth, with nature.”

Suzuki places some of the blame on corporations who, while at the bargaining table, frame environmental issues as problems that will cost them money and jobs. “They’re always the ones that carry the most weight.”

And he also recalls writing a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau after his government bought the Trans Mountain pipeline in 2018, saying that he supported him after he went to Paris in 2015 for the United Nations Paris Climate Agreement “and you said all the right things,” but then went ahead and invested in the pipeline.

“I said, ‘Why are you in politics? Isn’t it to protect a future for your children? You’ve got young children. What you’ve just done is going to reverberate through the lives of your children. Doesn’t that matter?’ And his response to me is he stopped answering my letters.”

Suzuki acknowledges that the prime minister loves his kids, but that politicians have to “play within a game that is dictated by ‘When is the next election? And whatever I do, it’s got to pay off before the next election.’”

He also empathizes with environmental defenders like Greta Thunberg, the 17-year-old Swedish climate activist who faced attacks from right-wing politicians and groups.

“Are you’re kidding? Are you kidding?” he says, exasperated when I ask if he’s faced the sort of vicious vitriol that someone like Thunberg has. “I’ve had bullets fired through our window in our home in Vancouver. Someone shot through the window. We had all the battles over forests back in the 1970s and 1980s.”

He recalls being called an enemy of British Columbia because he took on the forestry industry and how CEOs from the industry sat on the board of governors of the University of British Columbia, where he taught.

“You can bet that they wanted me fired. They wanted me to shut up, but I had tenure. Tenure was my great gift from society that ensured that I could say the truth or speak out as I saw the truth without fear of getting fired.”

David Suzuki and the Future of Environmentalism

Suzuki used to liken the environmental crisis to a car heading toward a brick wall at 100 miles an hour with no one screaming to slam on the brakes. Now, though, he likens it more to the old Roadrunner cartoons — in particular, the part where Roadrunner approaches the edge of a cliff and does a 90-degree turn but Wile E. Coyote goes right over the edge.

“And there’s that moment in time when he suddenly realizes, ‘Oh shit, I’m off the edge.’ And then down he goes. That’s where we’re at.”

Not exactly reassuring, but he does add, “That’s not an excuse to say we can’t do anything because I think it matters whether we fall 50 feet or 500 feet.”

So what, then, gives Suzuki optimism about the future of environmentalism?

“To me, the only real hope we have are the remnants of Indigenous cultures around the world because they’re based on a radically different way of seeing their place in the world,” he explains. “They understand that we live in a web of relationships with other life forms and with air, water and soil. And in understanding that, they acknowledge they’ve got a responsibility. You don’t want to screw it up. They give thanks to the Creator for nature’s generosity and abundance. But in giving thanks, they make a promise or commitment — they’ll do their best to ensure that nature will be protected so she can continue to be abundant.”

He adds, “That reciprocity, the responsibility that comes with receiving, is missing in the dominant society. It’s certainly absent in corporations.”

Suzuki acknowledges that “we pounded the hell out of Indigenous people around the world because they’re regarded as an impediment … because we want what they own” but says, “They’ve hung onto that culture and they’ve got a lot to teach us.”

He does admit, though, that the fire he has in his belly to keep fighting for the environment and hosting The Nature of Things into his mid-80s is “a fire that’s fuelled by a tremendous sadness” before referring to his twin granddaughters, who are now just over two years old.

“But now I’m just driven by the acceptance that this is where we’re going,” he says of the environment. “I’m going to do everything I can to try to make a difference in how far we fall over that cliff and just celebrate that these twins have come into my life and are an absolute joy. That’s all I can do.”

RELATED:

David Suzuki on Aging Well and the Secrets for Living Longer, Better