The Prince of Hearts: Remembering Canada’s First Royal Tour 160 Years Later

Over 160 years ago, Canada welcomed 18-year-old Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, pictured here in 1860, to Canada for the county's first royal tour. Photo: Otto Herschel Collection/Stringer/Getty Images

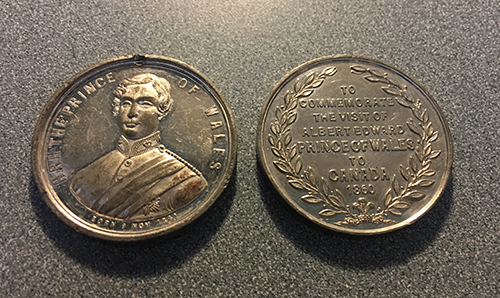

In 1860 Queen Victoria sent her 18-year-old son across the pond to Canada. It was our first royal tour, and it caused a sensation and started a tradition for the many tours that followed.

Sixteen-year-old Lizzie Wilmot of Cobourg, Ont., was consumed with excitement. “Everybody in town was agog over the impending celebration,” she recalled more than 60 years later. “New gowns, decorations and surmises as to whom should dance with the Prince were the topics of the day … and locally, Mrs. Connells had fitted many fluttering hearts with taffetas and tarlatans and heavy embroidered satins.”

The focus of so many fluttering hearts was Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, the second of Queen Victoria’s nine children. The queen would have raised an eyebrow at the notion of her teenaged son as royal heartthrob since she found him rather plain (“handsome I cannot think him”). Nonetheless, in the summer of 1860, scores of young Canadian women nursed the impossible fantasy of winning the heart of the heir to the throne and becoming queen of Great Britain and the Empire.

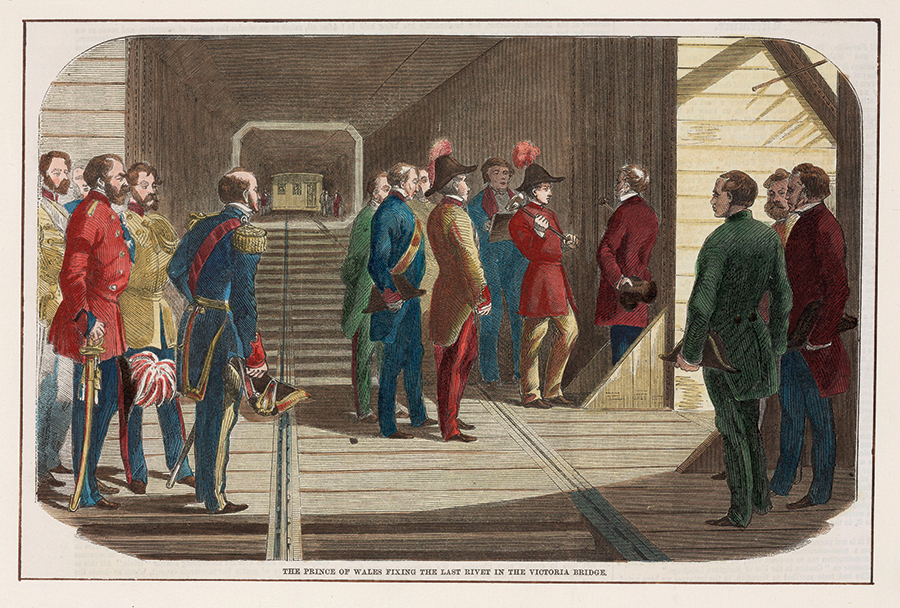

The impetus for a royal visit to North America had begun with the construction of a Montreal railway bridge across the St. Lawrence that was hailed, with civic hyperbole, as “the eighth wonder of the world.”

In May of 1859, the Parliament of the United Canadas invited Queen Victoria to officiate at the opening of this bridge that would be named in her honour. The queen was unable to attend, but it was decided that the Prince of Wales should come in her stead. Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, thought it would be good for Bertie, as he was known within the family, to make the first royal tour to North America. But they had plenty of misgivings. Bertie had always been their problem child. Prince Albert thought him rather dim since he did not excel at the strict Germanic schooling regimen he had devised for his children. Bertie’s elder sister, Vicky, in contrast, was able to discuss books with her father in three languages by the age of six. Yet some of Bertie’s more sympathetic tutors reported on his kind nature and affable manner, which they thought would serve him well in his royal role.

So it was that on July 10, 1860, the Prince of Wales and his retinue left Plymouth, England, on board the 91-gun HMS Hero, accompanied by steam frigate HMS Ariadne. On the morning of July 24, the prince stepped ashore in St. John’s, Newfoundland, to deafening cheers from thousands of spectators who had spent the night carousing and setting off fireworks. Despite a sudden downpour, the cheers continued as the prince processed in an open landau through the ceremonial arches erected across streets hung with patriotic banners, flags and bunting. At a ball that evening, the young prince danced with great gusto till 3 a.m., and a reporter from the New York Herald cheekily observed that: “His Royal Highness looks as if he might have a susceptible nature and has already yielded to several twinges in the region of his midriff.”

As Hero departed for Halifax the next day, all aboard agreed that the St. John’s visit had been a great success. In Royal Spectacle, his definitive study of the tour, historian Ian Radforth cites a letter from the prince’s governor, Maj.-Gen. Robert Bruce, to Prince Albert, reporting that his son had “entered cordially into the spirit of the thing.” The Prince Consort replied that all he knew about the place was the Newfoundland dogs and thus he could only picture the Prince of Wales “surrounded by these animals and their taking an animated part in the prevailing enthusiasm.” A Newfoundland dog was, in fact, presented to the prince, and it soon became a favourite of the crewmen on Hero.

“Halifax did not know itself on the 30th of July,” wrote the correspondent for The Times of London. “It was completely buried in green leaves and flowers and metamorphosed into a gigantic bouquet.” Other Maritime capitals such as Fredericton and Charlottetown followed suit, and evergreen trees and branches were used to disguise every shanty and shabby building. When the royal flotilla approached Montreal on Aug. 25, the steamers plying the St. Lawrence were ornamented with spruce trees and “even the very buoys were decorated.” As the largest and richest city in British North America, Montreal was determined not to be outdone in the splendour of its celebrations. Cannons boomed as the young prince stepped onto Bonsecours Market Wharf, and a crowd of 50,000 roared its welcome. In Radforth’s description, an enormous red and white pavilion stood on the wharf below which red carpeted stairs led up to a dais with a gilded throne. The prince was escorted up these stairs by the mayor of Montreal, Charles-Séraphin Rodier, who had draped his rotund figure in scarlet robes lined with white satin in imitation of the Lord Mayor of London. Rodier then proceeded to read his grandiloquent welcome in English and French and bowed so low each time the Crown was mentioned that his ceremonial sword poked skywards and his chain of office jingled against his boots, to the amusement of the foreign press.

That afternoon, the prince laid the final stone of the Victoria Bridge, which became the scene of a spectacular evening fireworks display. Two days later, he attended what was billed as “the largest ball ever held on the Continent,” hosted in an elegant wooden pavilion constructed at the foot of Mount Royal. Surrounded by gardens lit by twinkling lanterns, the hall featured refreshment tables with fountains of champagne encircling a 300-foot dance floor on which the prince danced tirelessly till 5 a.m. The next night, more than 8,000 citizens dressed in their finest gathered in the ballroom for a gala concert that included a cantata written in the prince’s honour. The following day, he took part in a military review and paddled in a flotilla of birchbark canoes with Indigenous Canadians. As the royal party departed for Ottawa on Aug. 31, the ballroom complex began to be dismantled. In a more lasting tribute, Mayor Rodier erected a statue of Bertie atop his house on Rue Saint-Antoine and dubbed it Prince of Wales Castle.

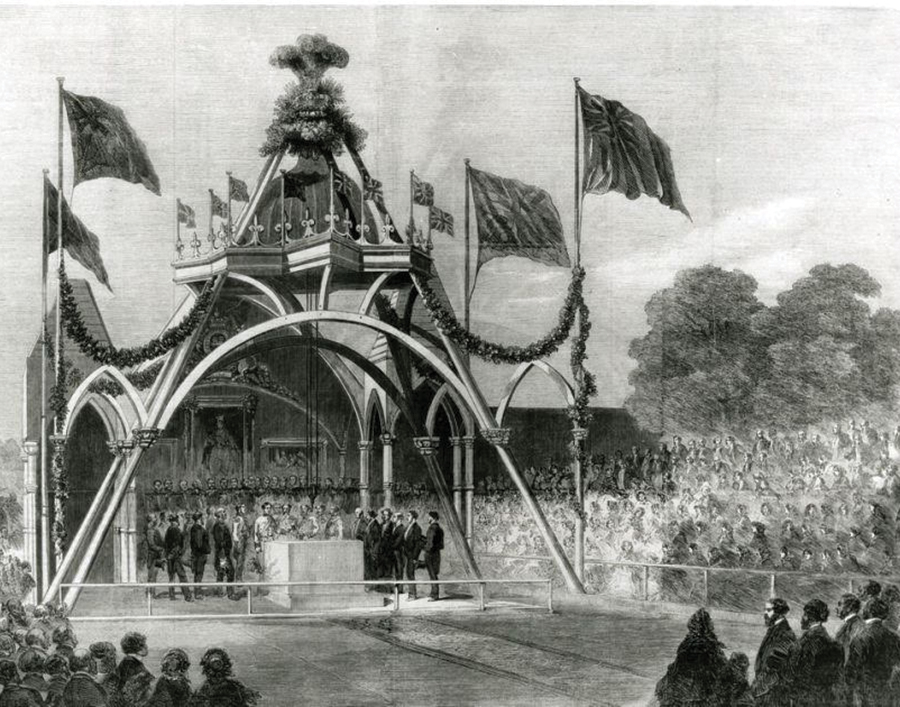

A Gothic pavilion had been erected in Ottawa for the laying of the cornerstone of the new parliament buildings. The prince also visited Chaudière Falls beside which an enormous ceremonial arch had been constructed by Ottawa’s lumbermen using 180,000 feet of sawn lumber and assembled without a single nail. Lumbermen in neckerchiefs then escorted him on a thrill ride down the timber slide by the falls.

So far, the royal visit had been a smashing success but, on Sept. 4, as the prince’s party sailed on the lake steamer Kingston through the Thousand Islands in perfect sunshine, a storm was brewing that threatened to disrupt the entire tour. In Canada West (which became Ontario after Confederation), the Protestant Orange Order was a powerful force and the bane of the Roman Catholic Church. The Orangemen were dismayed by how prominently the Catholic clergy had received the prince in Quebec and were determined to show that they were the most loyal followers of the Crown in this part of Canada.

The Duke of Newcastle, the man in charge of the tour, had made it clear that sectarian dissension must not mar the prince’s visit and had asked local authorities to prevent the Orangemen from co-opting the celebrations. But as the royal party sailed into Kingston harbour, thousands of Orangemen stood massed on the wharf in colourful sashes with fluttering banners and a brass band blaring out Orange marching tunes. Suddenly, the steamer Kingston veered away from the wharf and anchored out in the harbour. The mayor of Kingston came out by boat to meet with the duke and proposed that the prince’s procession detour around the Orangemen and their two ceremonial arches. The duke stated that unless the Orange display was removed by nine the next morning, the prince would not come ashore. That night the Orangemen held a No Surrender rally and loudly denounced the whole thing as a Popish plot. The following day, the Kingston sailed away from the town to the great disappointment of thousands onshore.

The next stop was Belleville where 10 ceremonial arches had been erected and every building bedecked with flags and flowers and banners. But when an emissary of the governor general reported that a crowd of militant Orange brethren had arrived by train from Kingston, a furious Duke of Newcastle gave the order to sail for Cobourg. The Kingston Orangemen, however, would not be deterred. With drums beating, they boarded a train for Cobourg – a train that would never reach its destination. As the Duke of Newcastle described in a letter to Queen Victoria: “By some curious accident (which will sometimes happen when the Government has the road in its own hands), the train broke down in a wild part of the line.”

Crowds jammed the Cobourg pier that evening as the prince disembarked from the Kingston and climbed into a carriage that local men then pulled to the new town hall. During the speeches that followed, in the words of one newspaper: “The Cobourg folks rang out their huzzahs loudly and freely.” With the building now officially named Victoria Hall in honour of his mother, the prince went inside so the dancing could begin.

Never shall I ever forget the evening of the ball,” recalled Lizzie Wilmot in capital letters. “I wore a snowy grenadine with puffed white sleeves and long frilled skirt and a wreath of pink rosebuds on my hair. The ballroom with its blazing gas fixtures ablaze with light, the gay uniforms and handsome gowns was a fairy land to me.” After the prince departed at about 3 a.m., Lizzie recalled: “…there was a great rush to see who could be the first to drink out of his wine glass. I do not remember participating in this.”

Despite his late evening, the prince was up early the next morning for a 9:30 departure for Rice Lake where he boarded the steamer Otonabee for a trip to Hiawatha First Nation. The tour’s physician, Dr. Henry Acland, was charmed by the view from the steamer and created a colour sketch as well as some quick studies of the Mississauga people in canoes. An arch had been erected at the Hiawatha landing place, and local men fired their guns in welcome as the steamer approached. The Mississauga chief presented the prince with a ceremonial scroll and birchbark baskets filled with beadwork and other handicrafts. Acland would continue to paint and draw Indigenous people throughout the tour and, in Toronto, he sketched a young Mohawk from the Six Nations Reserve named Oronhyatekha. This was the beginning of a lifelong

friendship during which Acland, a professor of medicine at Oxford, helped Oronhyatekha study there. Oronhya-tekha became a distinguished physician, athlete and Mohawk statesman.

After brief stops in Peterborough and Port Hope, the royal party boarded the steamer for Toronto where huge crowds waited to greet him on the waterfront near a towering ceremonial arch. But another arch, erected by the Orangemen near St. James Cathedral at King and Church streets, would bring simmering sectarian tensions to a boil. Atop its 60-foot tower was an illuminated King William of Orange, who had defeated the army of the Catholic King James II in 1690. The Duke of Newcastle had given orders that this arch be dismantled, but civic officials reached a compromise with the city’s 20 Orange lodges whereby King Billy and the Orange regalia would be removed.

When the prince arrived at the cathedral for Sunday morning service,

his carriage carefully avoided the unadorned arch in front of the church. During the service, however, a group of militant Orangemen arrived to drape the arch in banners. When the prince and his party emerged from the church, some Orange militants tried to pull the prince’s carriage toward the arch. The quick-

thinking coachman, however, managed to make a speedy getaway, and the police then subdued the crowd with only two arrests being made. The New York Times wrote a highly coloured account of the disturbance, and other U.S. and U.K. newspapers followed suit, though any shade cast on the tour was only temporary.

It seems to have affected Bertie very little. At a ball in London, Canada West, a few days later, he danced with such enthusiasm that it enlivened the entire proceedings. A memento of that evening is a particularly beautiful blue-silk taffeta and tulle ballgown worn by Susan Paul, the daughter of a St. Thomas mill owner. Miss Paul was not on the prince’s dance card but when the young lady selected for the “Nachtwandler” waltz tarried with her previous partner, the prince swept Miss Paul onto the floor instead. It is said that the young woman who missed her dance with the prince never spoke to the Paul family again.

Today, the blue gown is in the collection of the Elgin County Museum.

No tour of Upper Canada would be complete without a visit to Niagara Falls where the tour headed next for a few days of sightseeing and relaxation. A highlight was a tightrope-walking performance across the Niagara gorge by the celebrated daredevil Charles Blondin. The prince urged Blondin not to take any special risks, but the Frenchman responded by taking a man across the gorge on his back and then returning on stilts, an escapade the prince described as “nerve-wracking.”

The next week, Bertie once again danced till 3 a.m. at a ball in Hamilton’s Royal Hotel and was then up the next morning to open an agricultural exhibition at the city’s Crystal Palace. He took lunch with Sir Allan MacNab, the former premier of the united province of Canada, at Dundurn Castle, which to Bertie likely resembled an English country house more than a castle. After lunch, he boarded a train for Windsor and then Detroit for the start of his five-week American tour. The U.S. visit was intended to be unofficial, but huge crowds greeted him everywhere – 30,000 in Detroit, 50,000 in Chicago and 500,000 for a procession down Broadway in New York. So many people turned up for a ball at New York’s Academy of Music that the floor collapsed and had to be repaired. This caused no injuries but delayed the dancing till midnight. At a White House levee hosted by U.S. President James Buchanan, the East Room was so mobbed that people stood on chairs and ladies clambered onto the shoulders of men to catch a glimpse of the prince. The tour ended on Oct. 22 in Portland, Maine, where crowds in the harbour cheered and waved handkerchiefs as the prince was ferried out to Hero for the trip home.

By any measure, the visit had been a success. The American newspapers rang with praise for the young prince, who, with his charm, good humour and spirited dancing, had shown a new face of royalty to the New World. In Canada, seven years before Confederation, the tour, in the words of John A. Macdonald, had “called to the attention of the civilized world … the position and prospects of our magnificent country.” It had also been the making of Bertie. Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter Vicky that he had been “immensely popular everywhere” and “deserves the highest praise” before adding perceptively “all the more as he was never spared any reproof.”

This thawing in her feelings toward her eldest son was not to last and,

during the 41 years that remained before he became king, Victoria refused to allow him access to state papers. She disapproved of his reputation as “the playboy prince,” a sobriquet earned by his succession of mistresses. Bertie indeed had a “susceptible nature” as noted at his first ball in Newfoundland. But were there any dalliances on his 1860 tour? In Cobourg, there was a longstanding rumour that a man in town who bore a resemblance to King George V (Bertie’s second son) was Bertie’s love child. Some even claimed he received regular cheques from Buckingham Palace. Similar stories circulated in other Canadian towns, but they are almost certainly urban legends since Maj.-Gen. Bruce would never have allowed his young charge any opportunity to slake the twinges in his midriff during the tour.

There is evidence, however, that the prince who became King Edward VII in 1901 may have fathered some illegitimate children in England. One of these may have been a daughter of Bertie’s last mistress, Alice Keppel, who was married to a grandson of Sir Allan MacNab, the man who had hosted a lunch for Bertie in Hamilton.

In a further twist, Alice Keppel’s great-granddaughter, Camilla Shand, would become the mistress and then wife of the present Prince of Wales. On Nov. 4, 2009, Prince Charles and Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, visited Dundurn Castle, and she became the royal patron of this historic Hamilton landmark.

Royal Tours to Canada Over the Years

The 1860 visit by the Prince of Wales set the style for dozens of later royal tours of Canada. Here are a few of the most memorable.

1901 Prince George and Princess Mary

Prince George (later King George V) and his wife, Princess Mary, arrived in Quebec City on Sept. 16, 1901, and toured to Vancouver and back again. Like his father 41 years before, the prince rode a timber slide in Ottawa and was presented with a Newfoundland dog in St. John’s, N.L., (then a Crown colony).

1919: Edward, Prince of Wales

The informal style of the 25-year-old heir to the throne made for less ceremony and more meetings with the public during his cross- Canada tour in August 1919. It included a three-day canoe trip on the Nipigon River with Ojibwa guides. The prince later acquired a ranch in Alberta, which he visited on subsequent tours and even after his abdication from the throne in 1936.

1939: King George VI and Queen Elizabeth

With war clouds looming, this tour was designed to encourage Dominion solidarity. It also included a strategic four-day trip to Washington and a state dinner at the White House. The royal couple visited every province and inaugurated the National War Memorial in Ottawa and the Queen Elizabeth Way in Toronto. Queen Elizabeth would later tell Prime Minister Mackenzie King “that tour made us.”

1951: Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip

Visiting in place of her ailing father, Princess Elizabeth and her husband were greeted by enthusiastic crowds all across Canada. In Toronto, they attended a hockey game and, in Ottawa, a square dance at Rideau Hall.

1959: Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip

This remains the longest royal tour in Canadian history. The Queen and Prince Philip visited all 10 provinces and two territories, covering 15,000 miles in 45 days, making 400 appearances and shaking well over 7,000 hands. She inaugurated the St. Lawrence Seaway with U.S. President Eisenhower and also visited Washington and Chicago, where she made it clear in her speeches that she was there as Queen of Canada.

1982: Queen Elizabeth

Full Canadian sovereignty came into effect with the signing on Parliament Hill of the Constitution Act of 1982 by Her Majesty, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Justice Minister Jean Chrétien.

1983, 1986, 1991: Prince Charles and Diana, Princess of Wales

The royal couple’s first visit to Canada after their wedding was to

Nova Scotia and Newfoundland in 1983. In 1986, they visited Vancouver to open Expo ’86. The most famous moment during a ’91 visit to Ontario came when Diana greeted her two young sons, William and Harry, with a joyous hug after they ran up the gangway of the royal yacht Britannia.

2002: Queen Elizabeth

A 12-day Golden Jubilee Tour by the Queen and Prince Philip celebrating her 50 years as Queen of Canada was highlighted by the first royal visit to Nunavut and the first time Her Majesty dropped the puck to open a hockey game.

2011: Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge

Two months after their wedding, the newlyweds were greeted with great enthusiasm. At his final speech in Calgary, Prince William echoed his great-grandmother’s comment after the 1939 tour by saying, “Canada made us.”

A version of this article appeared in the Nov/Dec 2020 issue with the headline “Prince of Hearts,” p. 90.

RELATED: