E.J. Hughes: Exploring the Art, and Legacy, of One of Canada’s First War Artists

Hughes, photographed at the end of his service among some of his war paintings. At the top left is ‘After a Movie at Kiska’ and, in clockwise order, next to it is ‘Canteen Queue, Kiska,’ followed by ‘Unloading Supplies, Kiska,’ ‘Patrol Dismissing in Camp,’ ‘Patrol, Kiska,’ and 'Ten Minutes Rest – Kiska.’ In his hands he is holding his graphite study for ‘Route March’ (1946). Photo: Malak Karsh

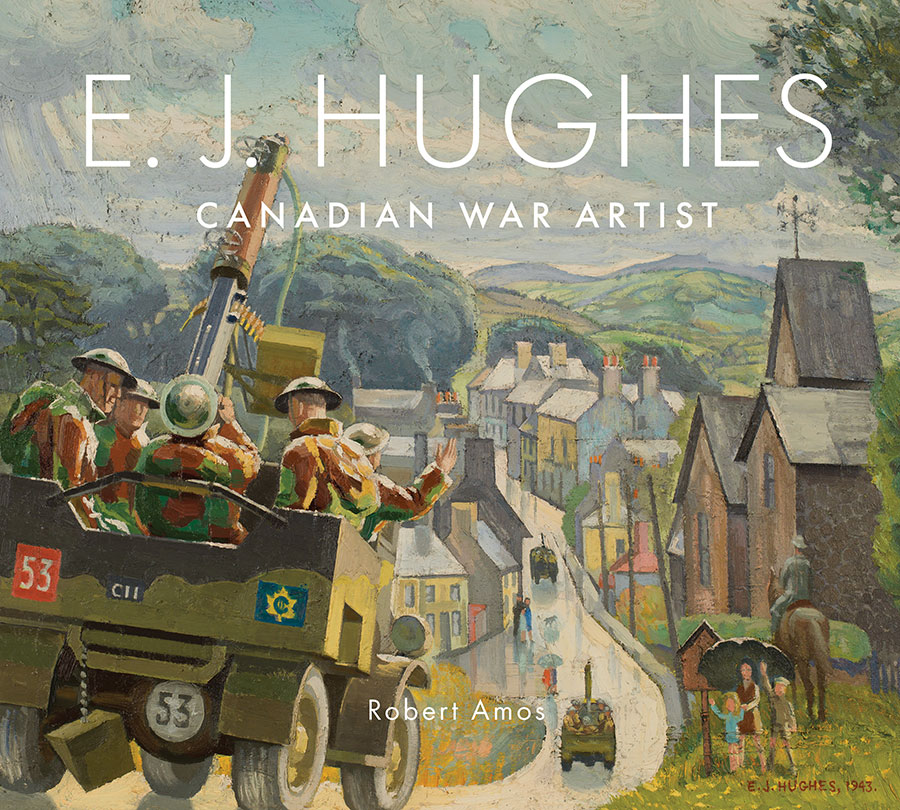

In the book E.J. Hughes: Canadian War Artist — the third book in Robert Amos’ series on the celebrated Vancouver-born painter — the author explores Hughes’ work chronicling the lives of Canadian soldiers during the Second World War. As Amos notes, Hughes served as “one of the first three service artists in the Canadian Army” — a record of work that until 2010, was “a story which had never been told.” As a war artist, Hughes travelled throughout his homeland as well as England and the Aleutian Islands, near Alaska, in some less than ideal conditions to record the daily lives of Canadians at war.

In honour of Remembrance Day we share art and an excerpt from E.J. Hughes: Canadian War Artist, which details Hughes’ early years, how he came to illustrate Canadian soldiers and how interventions from fellow artist Lawren Harris and a kind neighbour ensured that his artistic legacy — and this story — live on.

Canadian artist E. J. Hughes was a notoriously private man. He went to great lengths throughout his long life to reserve his time for painting and felt he was not suited to social life. In 1951, Max Stern, the owner of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, met Hughes and contracted to buy all the artworks Hughes produced. From that point, Stern took responsibility for the artist’s career, beyond the activity of painting. Since then, Hughes’s paintings have achieved great renown and hang in all the best Canadian art museums and many significant private collections. They have on occasion sold for more than two million dollars. Beyond these facts of his professional life, very little about Hughes is known.

Hughes was a student in the early years of the Vancouver School of Art, which he attended from 1929 to 1935, and subsequently he was recognized as the most talented artist of his generation on the West Coast. But the Great Depression made an art career impossible at that time. After graduation, Hughes created prints and murals, but they didn’t bring in enough income to live on, and as he was planning marriage to Fern Smith, he needed employment. Reflecting on the years he had enjoyed as a cadet, he enlisted in the army on August 30, 1939. This was just days before the commencement of the Second World War.

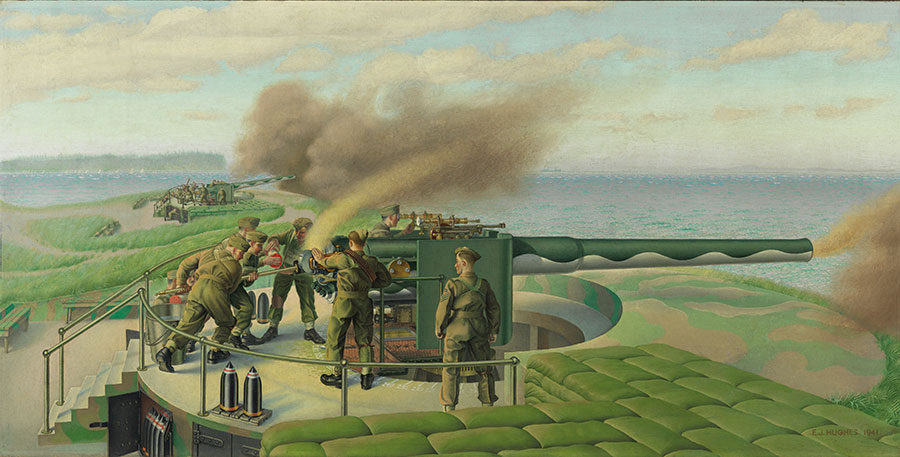

With a salary secured, Hughes married Fern in February 1940, but his active service complicated their early married life. Hughes had joined up as an artillery man, but almost from the start he had higher ambitions than serving as a gunner. Through his teachers, Fred Varley and Charles H. Scott, Hughes was aware of the War Art Program of the First World War, and he began writing to his superiors, asking for a role as a war artist. At the time there was no war art program. However, his persistence paid off, and early in 1941, he was posted to Ottawa as one of the first three service artists in the Canadian Army.

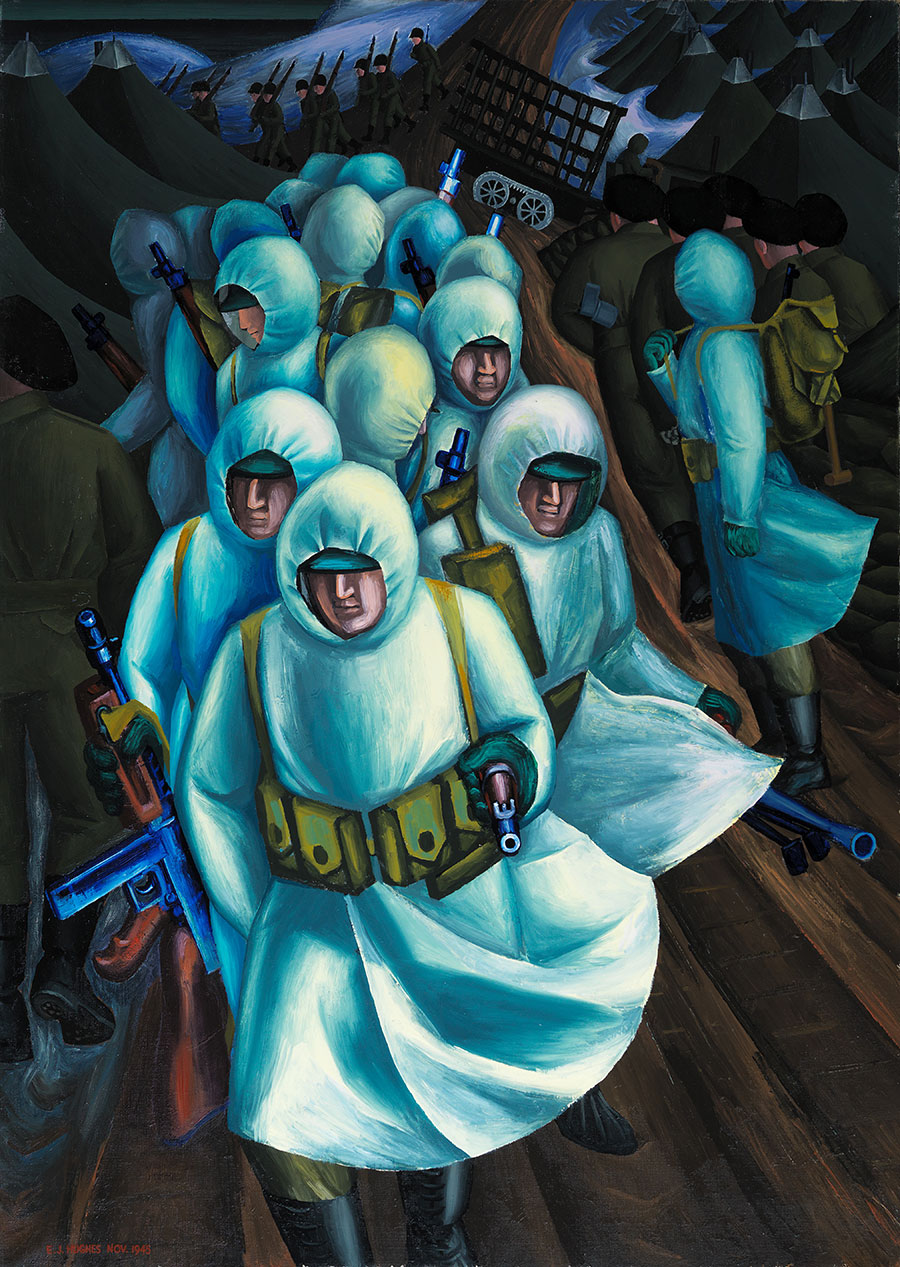

After two winters recording the life of the troops at Ottawa and Petawawa, in March 1942, Hughes was stationed in England. There he began making detailed drawings and watercolours. In February of 1943, the Canadian War Art Program became official. He was posted back to Ottawa in the summer and, later that year, was sent to Kiska, the westernmost of the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska. The freezing conditions and hours of darkness during the months he spent there were not conducive to making detailed drawings, so he transformed his style and began creating small, expressive oil paintings on wooden panels.

On his return to Ottawa in 1944, Hughes felt the influence of other war artists whose work was bigger and bolder than his. Two visits to the Metropolitan Museum in New York as well as reading books about Mexican muralists inspired him to create larger oil paintings with strong tonal contrasts and a focus on men rather than machines.

From 1944 to 1946, Hughes served as the administrative officer of the War Artists’ Studio in Ottawa, and as a result, he was the last of all the artists to be demobilized. Thus, he was the first, the last, and the longest serving of all Canadian War Artists in the Second World War and the most prolific.

Everything Hughes created during his years of war service—a total of 541 paintings and drawings—was retained by the Canadian Army. They were all transferred to the National Gallery of Canada in September 1946. Later, in October 1971, both the Canadian War Records of the Second World War and those of the First World War were deposited in the Canadian War Museum. Except for a few of his major oil paintings, very little of the body of work Hughes created has been exhibited.

When Hughes returned to civilian life in late 1946 he was thirty-three years old and found himself out of work. Despite his prolonged training and years of war production, he had never really sold a painting. Hughes and Fern, who had lived mostly apart during his service, now moved in with his parents in Victoria, and he began painting images that he had drawn before the war. Though the imagery was from his earlier days, he now painted in a manner entirely changed. Today we see in these dark and powerful canvases the evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder. Never again would he paint an explicitly war-themed subject.

There’s no telling how the artist would have proceeded without the intervention of Lawren Harris. Harris was the executor of Emily Carr’s estate and, in 1945, had arranged for the sale of her paintings through the Dominion Gallery in Montreal. With the funds realized from this, Harris created the Emily Carr Scholarship, which he awarded to Hughes in 1947. This enabled him to take a trip to Prince Rupert on the Princess Adelaide that summer. In the following year, Hughes travelled and sketched on Vancouver Island, and the drawings he made on these journeys laid the foundation for his painting career.

In 1951, Harris introduced Max Stern of the Dominion Gallery to the work of E. J. Hughes. Stern immediately sought out the artist at his home at Shawnigan Lake, and at that first meeting bought all the paintings Hughes had on hand.

At the same time Stern also contracted to purchase everything that Hughes would create in the future, an arrangement which continued for the next half century. From the start, Stern placed Hughes’s work in every major collection in Canada and, while the artist’s fame grew, Stern’s manage.ment soon allowed Hughes to lead a comfortable though quiet life. The story of Hughes’s professional career is told in my other books about the artist.

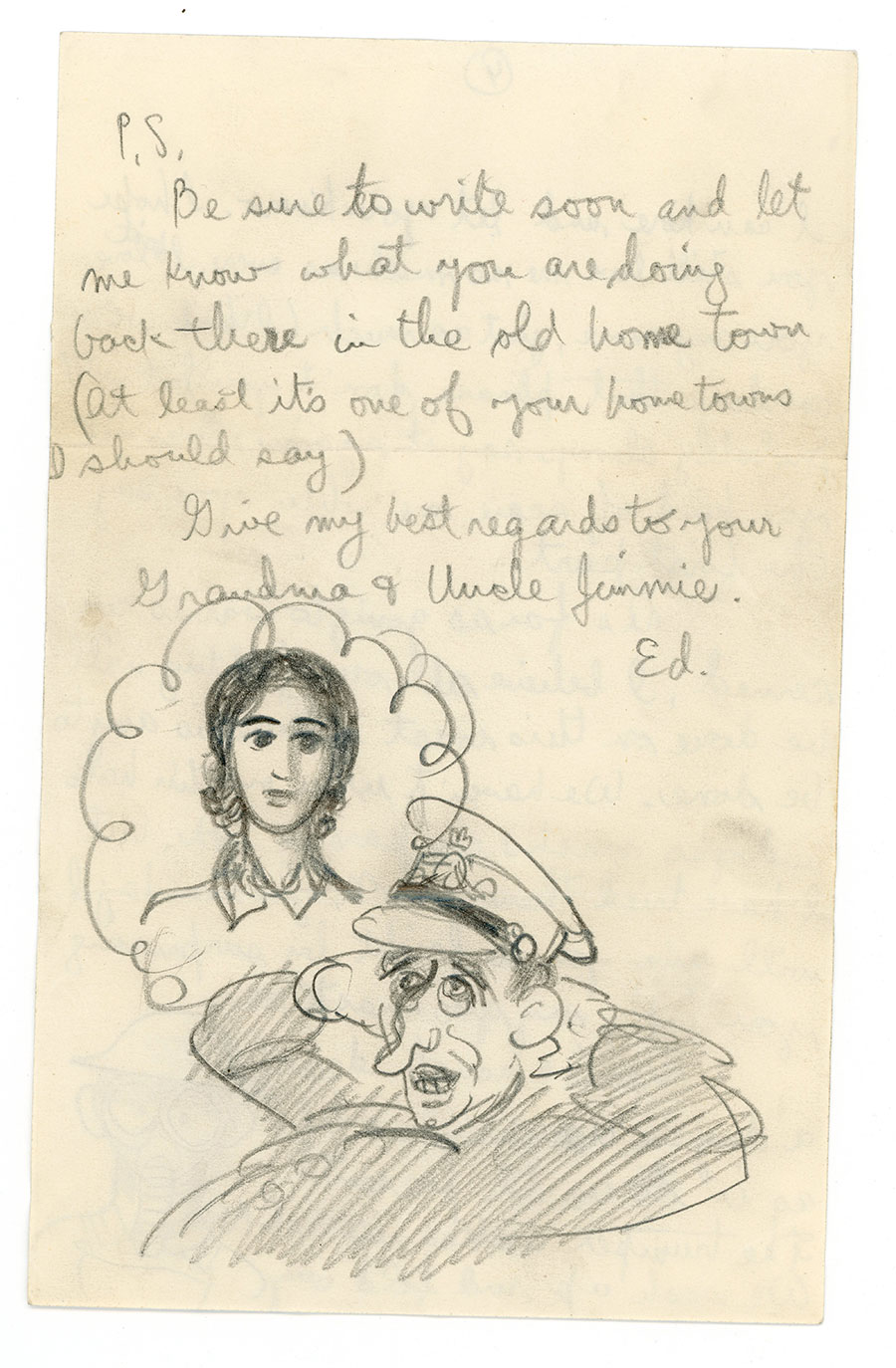

With the exception of a few charming letters Hughes wrote to Fern during his early training at Fort Macaulay, we have none of his writing from wartime. Yet he did save every one of Fern’s weekly letters, and these give some sense of the trials they lived through. Though Hughes never faced active combat, the anxiety of his wartime experience was relentless, and without doubt, he and his wife were shattered by the emotional strain of their life during wartime. Between 1940 and 1946, the two were repeatedly separated and then reunited. During those years, Fern became pregnant and then lost three children at or soon after birth. The couple remained childless, and Fern became progressively incapacitated with muscular dystrophy until her death in 1974.

In 1977, Hughes was befriended by a neighbour from Shawnigan Lake, Mrs. Patricia Salmon. Salmon dedicated herself, until the artist’s death in 2007, to learning and recording everything about Hughes, with the intention of writing his biography. In 2010, realizing that ill health would prevent her from finishing the project, she presented her archive to me. Included were the records of Hughes’s service as a war artist, a story which had never been told.

At last, with the papers Mrs. Salmon saved, the support of the Estate of E. J. Hughes and the assistance of the Canadian War Museum, we can understand how Hughes’s wartime service gave to his later and better-known work its subtle and unusual power.

Text by Robert Amos from E.J. Hughes: Canadian War Artist, text copyright © 2022 by Robert Amos. Reprinted with permission of TouchWood Editions.

RELATED:

How Canadian Painter Mary Riter Hamilton Broke Boundaries on the First World War Battlefields

How a Canadian Composer is Giving Her Grandmother’s Secret Holocaust Poems New Life Through Music

How the Second World War’s Greatest Battle Was Waged on Water