Love, Tony: Tony Bennett Talks Life, Art and Music

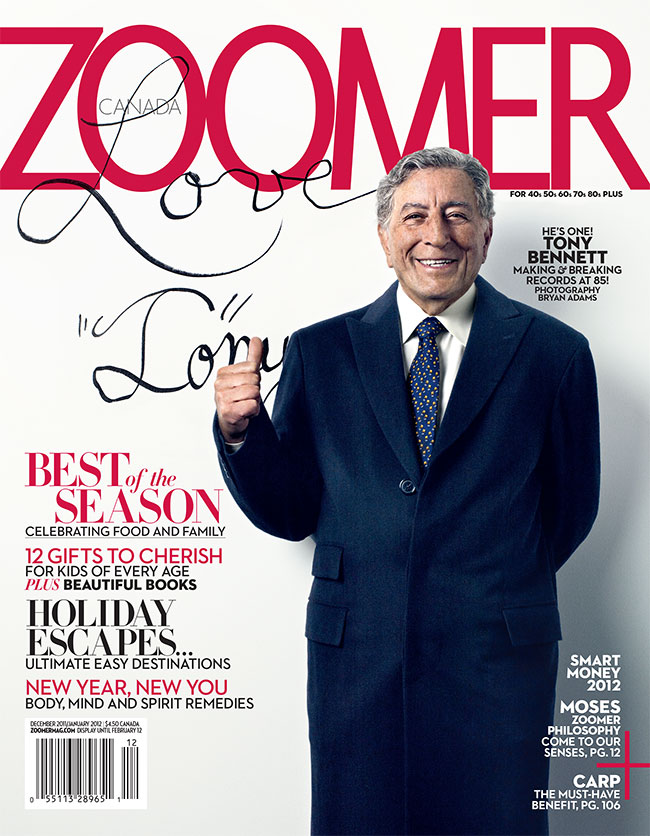

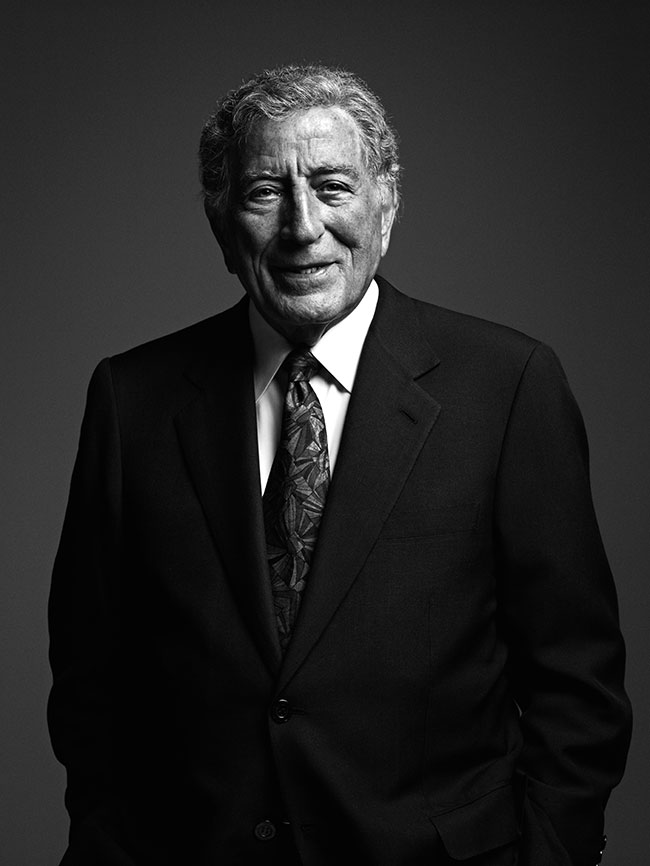

Tony Bennett, who passed away in July 2023 at the age of 96, spoke with Zoomer at his New York home in 2011. Photography: Bryan Adams

Tony Bennett’s New York condominium is nestled high in the Trump Park Tower on Central Park South. The uninterrupted expanse of his implausibly wide living room window affords a magnificent view of the park far below, which even on this clear mid-September day stretches northwards farther than the eye can see. Given that the iconic American crooner paints very nearly as well as he sings, it is unsurprising that when prodded to comment on it, he frames his answer in terms of what it inspires in his painting rather than his singing.

“It’s everything to me,” Bennett volunteers of the vista. “To have a view on Central Park and watch the four seasons and the great vastness of the sky—it changes every day. Rembrandt said it, ‘There’s only one master—that’s nature.’ It gives me unbelievable subjects to study and paint.”

In 2006, Bennett’s oil-on-canvas “Central Park” was accepted into the permanent collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. It is one of three of his paintings to be housed in a Smithsonian collection. His portrait of Ella Fitzgerald was acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and another, of Duke Ellington, hangs in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery —”Beside Obama’s,” Bennett pointed out to me, smiling broadly, when he showed me a small facsimile of the Ellington portrait that hangs in his foyer shortly after welcoming me to his apartment, a personal rendezvous for which he dressed just as he would for the public stage: a tailored navy blue suit, a powder blue shirt and a red silk necktie.

Another of Bennett’s painted tributes to a different old friend, “Homage to Hockney,” is on permanent display at the Butler Institute of American Art, in Youngstown, Ohio. And the relevance of this last fact is that Bennett has invited me to sit down with him and conduct his interview on his living room sofa, immediately beneath a large canvas that I can only take to be David Hockney’s reciprocal homage to Bennett. It is primarily an ocean view but, in the foreground, in one corner you find a small dog; in the other, tossed on the floor, a folded newspaper, with Bennett’s picture on its front page.

“Hockney put me in one of his experiments,” Bennett began when pressed for explanation and then paused, chuckling. “He painted that about 30 years ago, in Malibu, where he has a home. That was his favourite dog. That’s the Los Angeles Times. And the ocean, which he always painted there, different ways.”

We settle on the sofa with our backs to the painting, but now other mementos are proving just as captivating. For example, to our left, the window on Central Park is flanked by two framed sheets of music. At left, an ancient score handwritten by none other than Giacomo Puccini, which was a gift from Bennett’s son and long-time producer, Danny Bennett. The page on the right is more contemporary but just as enduring. “Intro — Porgy and Bess,” it says at the top. Closer inspection reveals a scrawled notation at the bottom right corner, which reads simply, “Gershwin, orchestration begun late 1934, finished Sept. 2, 1935,” signed “GG.” Another original, this time a gift from the collection of the Library of Congress arranged by Bennett’s late friend, the billionaire philanthropist John Kluge.

“The overture of Porgy and Bess, written by hand, by George Gershwin — I couldn’t believe it,” Bennett said, understandably, of the occasion of its presentation, when he sang at the library in May 2003.

On the ledge beneath the window, there sits a massive album of birthday greetings sent to Bennett a decade ago, on the occasion of his 75th birthday. And as when I arrived for our scheduled rendezvous, Bennett was running 10 minutes late, I had occasion to flip through it, under the discreet supervision of his publicist, Sylvia Weiner, Bennett’s striking wife, Susan Crow, and their far less trusting dog, a small bundle of yapping white fluff named Happy. What a read. Each page is affixed with a single letter — except for one, where someone thought it would be fun to overlap a pair of notes from Al Pacino and Robert De Niro. Barbra Streisand is in there, naturally, and so is Tina Sinatra. John Travolta sent a note containing a mystifying pictograph featuring a large airplane, possibly referencing Bennett’s hit recording of “Fly Me to the Moon.” Matt Groening, who helped Bennett connect with a new generation by making him a character on The Simpsons, also sent a note. And Donald Trump, whether from absent-mindedness or just chronic ingratiation, accidentally sent two. Naturally, some of the wellwishers are no longer with us (the great Oscar Peterson, Bob Hope, Ted Kennedy and more), while others have merely expired politically (Bill Clinton, Dick Gephardt). But for all the famous names, the most jarringly unusual feature of the book is surely the birthday greetings from his future in-laws. How many 75-year-olds have you met who had a set of those?

Bennett married his long-time girlfriend Susan Crow in 2007, when he was 80 and she 40. But that particular age-defying feat does not stand out in Bennett’s recent life. Instead, it was just another chapter in what was already a long-established trend. It began in the ’80s, when after two faltering decades, Bennett unexpectedly began to connect with a new, and younger audience, primarily through television appearances on late-night talk shows and MTV. Then in 1994, at age 67, Bennett capped the recent successes of a pair of Grammy-winning tribute albums (to Sinatra and Astaire) with a platinum-selling Grammy Album of the Year: MTV Unplugged: Tony Bennett. “It is cool these days to think that Tony Bennett is cool,” the New Yorker proclaimed in “Talk of the Town” that same year. And the following decade, his knack for turning back the clock became legend, when at age 80, he released Duets: An American Classic, featuring co-vocalists from Barbra Streisand to Sting, Bono and Elton John, which achieved platinum sales in his first month. When we sat down to talk in September, the sequel Duets II was still two weeks shy of scheduled release, but he was already planning on supporting it with concerts in the U.S. and Canada. To put that in context, imagine the Stones on tour in 2028.

A listen to the pre-release edition of Duets II cemented what the title makes clear: it is a sequel, its songs drawn from the same classic catalogue. But it is also an evolution, its list of contributing vocalists has a couple of repeat contributors in k.d. lang and Michael Bublé, while in the old-timers category Aretha Franklin and Willie Nelson make appearances. And where youth on the original only existed in contrast to the headline act, Duets II offered a taste of the real thing, in form of the irrepressible verve and character of the late Amy Winehouse and Lady Gaga. That last observation had me wondering how it was that a man long given to proclaiming that he is not contemporary and “doesn’t follow the latest fashions” came to know enough to ask singers like Winehouse, Gaga, Queen Latifah and even Sheryl Crow and John Mayer to record with him.

“My son [Danny] had everything to do with this,” Bennett readily admitted. “Most of [the artists] were unfamiliar to me.” And then he added somewhat unnecessarily, “Mine was a different era. Mine was Sinatra and Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald.”

Bennett’s early success was rooted in exactly their kind of music and only when his career imploded in the mid to late ’60s did he have a go at other styles, at the prompting of his record label, Columbia. In 1970, the regrettable attempt at reinvention culminated unhappily in an album called Tony Sings the Great Hits of Today! featuring songs from the likes of The Beatles and Burt Bacharach. Bennett reportedly hated the music so much that the recording sessions made him physically ill. So perhaps it was unwise of me to suggest, in jest, that Duets II could well be seen as that unfortunate LP stood on its head: Hit Makers of Today Sing the Great Hits of Yesterday!. Even so, the vehemence of Bennett’s response surprised me.

“I’m anti-demographic,” he began, waving his hand dismissively. “I never liked when [the record labels] split it up and said this is your music, and your parents like something else. I thought that was an incorrect way of treating the public. You know, if you’re an entertainer, you’re really just supposed to sing to an audience. You don’t care what their ages are—that’s almost a Nazi attitude.”

One would not expect Bennett to use the latter term flippantly; he was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1944 and served with infantry in France and Germany, where he ultimately helped to liberate a Nazi death camp. All the same, he continued. “The superior youthful thing — it should never have happened. I think it hurt the whole music business. Record shops are failing, and they’re wondering why. [It’s because nobody is] making records that become standards and last forever.”

Perhaps those flailing years of his mid-career, when he was marginalized by the music of youth, still smart. Regardless, the passion of his answer is less about him than his love for the classic American music of the first half of the 20th century. Hoagy Carmichael, Rogers and Hammerstein, Bart Howard, Frank Loesser, Vernon Duke and so on. What many call the Great American Songbook and for which Bennett has coined a different and more playful term: the Fred Astaire Songbook.

“You see, in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s, Irving Berlin, George Gershwin and Cole Porter would not have anyone introduce their songs except Fred Astaire. He was their favourite. He introduced ‘Night and Day’ and ‘They Can’t Take That Away From Me,’ and all that,” Bennett explained. “The songs were a renaissance in our young country. The public still doesn’t realize that it’s the best thing that we’ve ever contributed to the rest of the world. Because everybody in the world, no matter where I go, they love those songs. They know them. And I don’t know what popular songs are famous in Sweden or Norway or Germany or Italy. The Italians invented opera and symphonic orchestra, but popular music — what the British call ‘light entertainment’—I’m convinced that 35, 40 years from now, it will be called America’s classical music.”

To produce Duets II, Danny Bennett began by narrowing this formidable oeuvre down to those songs that his father had already successfully recorded. From there, he compiled a list of three each appropriate to every one of participating duettists. They, in turn, chose one which they wanted to record. And then, rather remarkably, rather than have the contributing artists come to him, Bennett set out on the road to record with each of them in their local studios. To London, for example, to record “Body and Soul” with Amy Winehouse at Abbey Road Studios (“What a talent,” Bennett says. “Such a tragedy. Everyone was praying for her.”). To Italy, to record “Stranger in Paradise” with Andrea Bocelli in the studio in his villa (“He gave us a great Italian meal afterwards — for the whole crew. That was fun!). Mariah Carey threw open her home studio, too. For Carrie Underwood, it was off to Ben’s Studio in Nashville. Queen Latifah preferred to record at Charlie Chaplin Studios in Los Angeles. Finally, Lady Gaga joined them at Bennett Studios (property of his son and sound engineer Daegal) in Englewood, New Jersey, to record “The Lady Is a Tramp,” the definitive track of the album. “She’s very, very creative,” Bennett says of Lady Gaga, who very obviously impressed him. “After all her performances, she’s really a very simple, very sweet Italian-American girl and thankful to everybody for believing in her. It’s very nice.”

In the final accounting, the 17 tracks were recorded in nine different studios across the United States and Europe. But rather than linger on his own efforts on this front, he complimented theirs. “I can’t believe this new group coming out of music schools,” he said. “They walked in very prepared. When Mary Clooney and I started in the ’50s, we’d run into the masters like Jack Benny or George Burns, and they’d say, ‘You guys are doing good, but it’s going to take you six to nine years before you really know how to perform. The audiences will have to teach you what to put in and what to leave out.’ You don’t feel this is happening with young performers. They’re [already] very prepared, very professional. They walk in with a good knowledge of the song, ready for it. It’s a good sign.”

Well, if Tony Bennett says so, so be it. Meanwhile, Duets II debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard chart, a first for Bennet — easily making the 85-year-old the oldest performer to ever climb to the top of charts. Savour this, for the only performer positioned to surpass the record has no plans for a Duets III. But then neither does he have plans to retire—from performing or from painting. As it happens, he attributes his longevity at each to his partaking of both.

“As soon as you get burnt out singing, you go over to painting,” Bennett explained of his approach to a long and productive life as our interview drew to a close. “As soon as you get burned out painting, you go back to singing—and it feels new again, every time. Maybe if you did just one thing, eventually you’d say to yourself, ‘I’ve got to take a vacation and get away from this.’ I never feel burnt out. To me, I’m on perpetual vacation. I’m very fortunate.”

Indeed.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2011/January 2012 issue.

RELATED:

Tony Bennett, the Timeless Crooner Who Bridged Generations, Dies at 96