The Canadiens and the Maple Leafs: The Glory and Heartbreak of Hockey’s Greatest Rivalry

Montreal Canadiens captain Yvan Cournoyer hoists the Stanley Cup with help from teammate Yvon Lambert after defeating the Boston Bruins 4-1 at the Boston Garden in 1978. The championship win marked the Habs' third in three years. Photo: Bruce Bennett Studios / Getty Images Studios / Getty Images

With the Toronto Maple Leafs and Montreal Canadiens duking it out in Game 7 tonight for just the second time in 16 NHL playoff series, we revisit this story by D’Arcy Jenish — author of the book The Montreal Canadiens: 100 Years of Glory — in which he recalls his childhood love of the Habs and the enduring rivalry between hockey’s two most storied franchises.

The fiercest rivalry in hockey history arguably began Nov. 2, 1944, when the Toronto Maple leafs visited the Montreal forum to play the Canadiens for the first time that season. The Canadiens were the defending Stanley Cup champions and, the previous spring, had defeated the Leafs in the semifinal. This night, the Leafs won by a 4-1 score.

But it was a bitter contest. The referee called 16 penalties, 11 against the home team. Outraged fans repeatedly littered the ice with hats, programs, pop bottles and whatever else was at hand. One Montreal journalist described the game as “a tale of slug and sock and whose teeth are these,” while Canadiens forward Ray Getliffe told a reporter: “We hate those guys so much we just want to kill them.”

It was an epic struggle — one of many between the Leafs and the Canadiens — this country’s version of a civil war. English versus French, Protestant versus Catholic, Toronto versus Montreal — all the underlying tensions that had bedevilled our fragmented and far-flung nation for a century were at play when these two teams met.

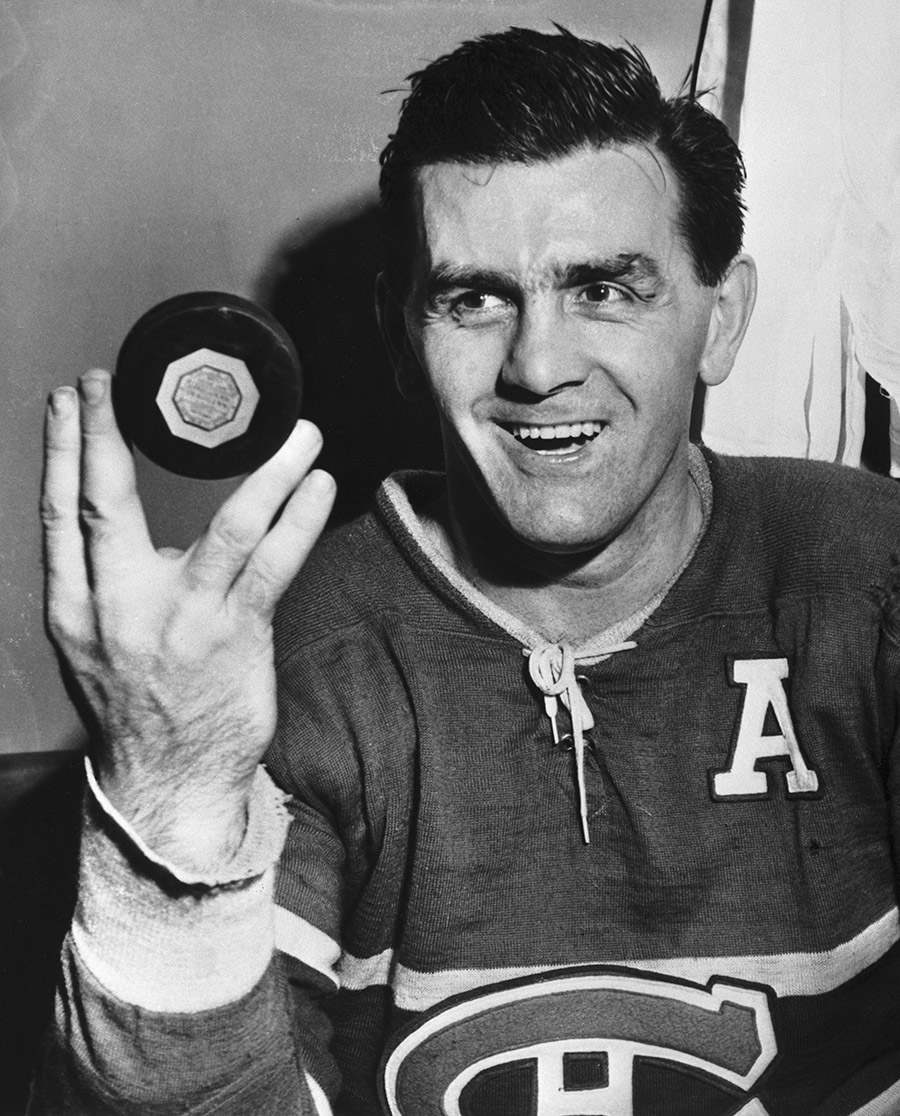

The Canadiens were again the class of the league in 1944-45. They racked up 80 points, accumulated a record 228 goals, and Maurice (Rocket) Richard did the unthinkable by scoring 50 goals in a 50-game season. He and his teammates should have waltzed to another Stanley Cup championship, but the third-place Leafs, who earned a mere 52 points, upset them in the semi-final, and Richard later confided to a journalist: “My wife will attest that I spent many sleepless nights during the summer thinking of nothing but that.”

Fifteen years later, growing up in south-eastern Saskatchewan, I began watching the Leafs and the Canadiens (or Habs as they’re affectionately known — short for habitants, early Quebec settlers) on a small television set that produced grainy black and white images.

For me and my pals — and for most Canadian kids of our generation — the National Hockey League was the most important sporting enterprise on earth, and the Leafs and the Canadiens were the only teams that mattered. Here and there, a few lonesome souls raised their voices for the NHL’s American-based entries — the New York Rangers, Boston Bruins, Detroit Red Wings and Chicago Blackhawks — but the rest of us could be divided into two camps: those who worshipped the blue and white of the Maple Leafs and those who idolized the bleu, blanc et rouge of the Canadiens.

I landed in the latter camp purely by chance. I borrowed from the school library a slender biography of Maurice Richard and was completely captivated. Here was a tale of a young man from a large French-Canadian family of limited means. He had learned to play hockey outdoors in the cold, hard Montreal winters — just as my friends and I were doing in another part of Canada with disturbingly frigid winters — and he had surmounted all obstacles to become the most dazzling goal scorer and ferocious performer the game had ever seen.

By the time I picked up this book, Richard was retired. But the Canadiens of the early 1960s remained an inspiring bunch. There were all those mesmerizing skaters with their fire-wagon red sweaters and French-Canadian names that sounded so exotic to a kid from Saskatchewan. Right winger Bobby Rousseau, my favourite, had blazing speed and a powerful shot. Jean Béliveau, the captain, combined a regal bearing with elegant style. Bernie (Boom Boom) Geoffrion was the man with the legendary slapshot. The team had the masked marvel Jacques Plante in net and little Henri Richard, the Rocket’s brother, who was fast and tenacious and always flying.

These guys and their English-Canadian teammates — Dickie Moore, Donnie Marshall and Ralph Backstrom, among others — were good. They finished first in 1961-62. A year later, they landed three points out of first but in 1963-64 were back on top again. Yet, they couldn’t win when it really counted — during the playoffs. The most agonizing moments of my youth occurred on successive Aprils between 1962 and 1964.

First, it was Bobby Hull and the Chicago Blackhawks who sent them to the sidelines early. Then, for two years running, it was the Leafs, the detestable Toronto Maple leafs beating my Montreal Canadiens in the semifinals.

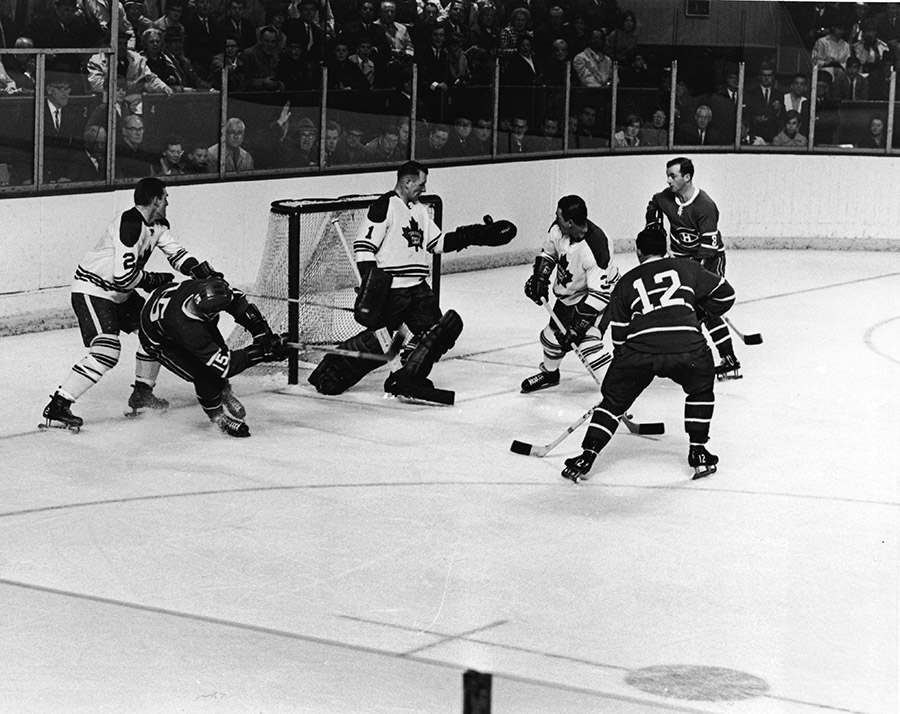

One spring evening, when the crocuses were in bloom, the meadowlarks sang and sensible children were out playing, I sat in front of that TV set watching the ageless wonder, Toronto goaltender Johnny Bower, stop the Canadiens cold again and again. Watching their big, bruising defence pairs, Allan Stanley and Tim Horton, Bobby Baun and Carl Brewer, drive the Montreal forwards into the corners and then smash them against the boards. Watching George Armstrong outplay Jean Béliveau, and Dave Keon out duel Henri Richard. It was so painful I sometimes went to bed with tears in my eyes.

And then, a year later, in the spring of 1965, all my prayers were answered. This version of the Canadiens had more speed with Yvan Cournoyer in the lineup, more fire and ferocity due to the presence of John Ferguson, more grit and tenacity after trading for Dick Duff, and a better defence with the addition of Jacques Laperrière and Ted Harris. They eliminated the hated Leafs in the semifinal and then went seven games against the Hawks in the final.

The only thing I remember about those two playoff series was the last game against Chicago. It was played on Saturday, May 1. It was a warm evening. Friends came knocking at the door, and my younger brother went out to play, but not me. There was only one place to be — in front of the TV.

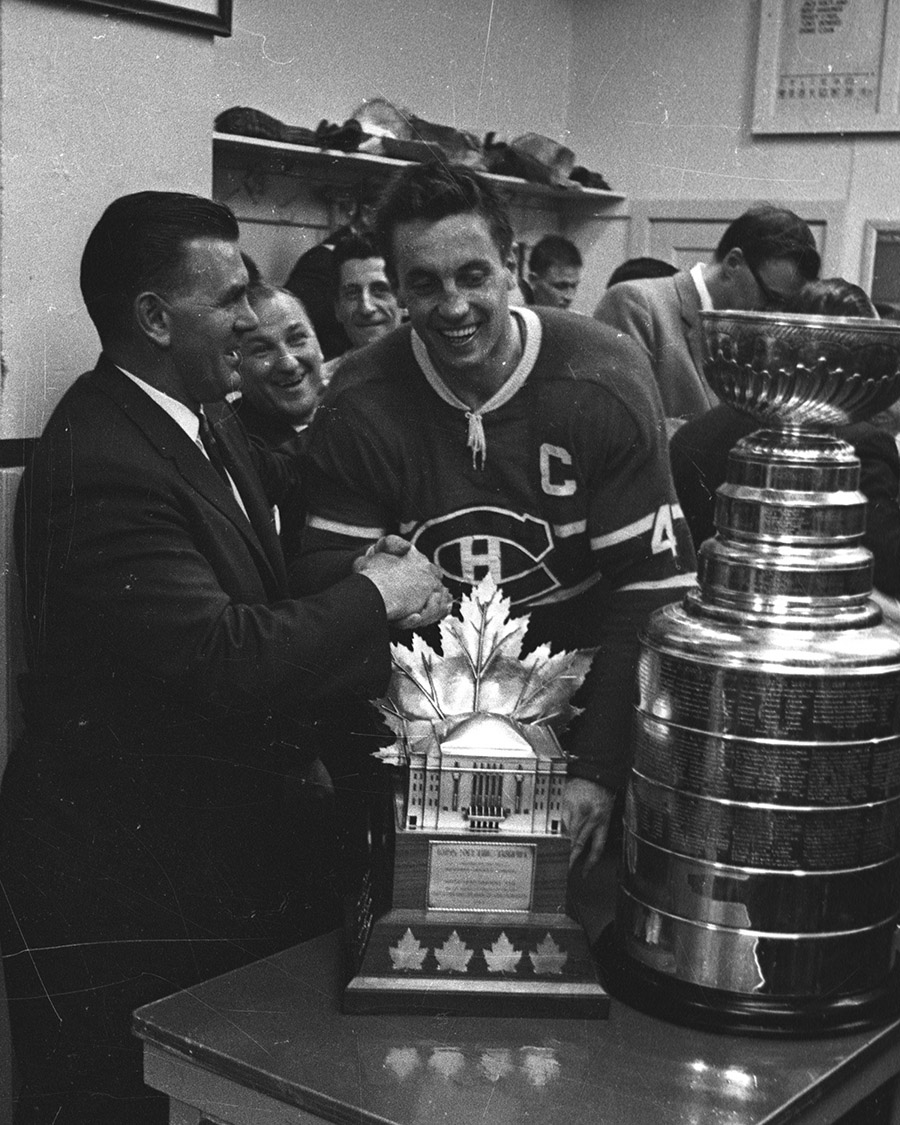

Fortunately it was all over early. Béliveau scored a strange goal 14 seconds in, and the Forum crowd began to chant and cheer and kept it up until Duff put the Canadiens up by two five minutes later. Cournoyer and Richard scored before the period was over, and that was it. The Hawks never even threatened. For the first time in my life, I saw a captain of the Canadiens hoist the Stanley Cup and lead a victory lap around the ice, and that night I shed tears of joy.

The Canadiens beat the Wings to win another cup the following season, and then in 1967 — Canada’s centennial year — they advanced to the final yet again. The entire country was in a celebratory mood that spring and so were Montrealers. They were about to welcome millions of visitors: fellow citizens and foreign tourists came to see the marvels of Expo 67. A world’s fair wasn’t enough for Mayor Jean Drapeau and the city’s rabid hockey fans though. They wanted another Stanley Cup championship.

But they were denied, and it was the nearly over-the-hill Leafs who yanked the coveted prize from their hands. Bower was by then 42 years old. Backup goaltender Terry Sawchuk was 37. Nearly a dozen more were over the age of 30. Leafs coach and general manager Punch Imlach had endured endless criticism for sticking with his veterans, but they won the Stanley Cup, beating the Canadiens in six games.

The sting of that defeat stuck with the players. “Of all the years I lost, 1967 is still the one that hurts the most,” Béliveau said in an interview with this writer 25 years later.

That ’67 series was the culmination of a fierce and prolonged rivalry. It was the 11th time since 1944 that the Leafs and Canadiens had met in the playoffs. Each side had emerged triumphant on five occasions, making the 1967 showdown the rubber match. To a child’s eye, the titanic clashes between Canada’s two NHL teams were just hockey. In retrospect, there was a lot more to it than that.

And with the advantage of hindsight, it is apparent that 1967 was a watershed for the country as well as its most celebrated sporting rivalry. The differences between Protestant and Catholic began to seem piddling in a nation that was becoming more secular and demographically diverse, the latter due to immigration from Italy, Greece, the Caribbean and Asia. The competition between Canada’s two largest cities was also being resolved — in favour of Toronto, which was emerging as the centre of corporate power in Canada and the favoured destination of newcomers from all those faraway lands.

Hockey was changing in ways that were equally profound. In 1967-68, the NHL doubled in size to 12 teams, and it would continue to expand over the next three decades until reaching its current stature of 30 teams. The addition of new franchises meant fewer games between the old clubs of the “Original Six” era, and fewer opportunities for anger, animosity and real hatred to arise between players and teams.

Perhaps more important, the battle for supremacy between the Leafs and the Canadiens was resolved unequivocally in favour of the Canadiens. They kept on winning championships — in 1968, 1969, six times during the 1970s and again in 1986 and 1993. The Leafs have never come close since their centennial-year triumph. The two old rivals have met only twice in the playoffs since then, in 1978 and 1979, with the Canadiens winning easily.

Sportswriters and TV commentators still refer to the Leafs and the Canadiens as the fiercest of rivals, and the players on both sides undoubtedly make a special effort when they line up against each other. But today’s pampered and muscular millionaires have no desire to kill an opponent simply because he happens to be wearing the blue and white or the bleu, blanc et rouge. The old rivalry between these two organizations has been robbed of the oxygen it needed to survive — high-stakes regular season games and life-or-death post-season matches.

These days, it is the spectators who make a game between the Leafs and the Canadiens one of the rowdiest and most enjoyable sporting spectacles this country has to offer. But the rivalry exists more in the minds of the fans than the hearts of the players. Over the past five years, while researching a history of the Canadiens to commemorate their centennial, I attended many games in both Toronto and Montreal. And what a hoot they were. If the Leafs were visiting Montreal, thousands would show up in blue and white sweaters. The Toronto supporters would take over with chants of “Go, Leafs, go” until irate Montrealers drowned them out.

The same happens in Toronto. Several thousand Canadiens fans take over the building if their side is winning. The most interesting thing about these bleu, blanc et rouge diehards is that they are overwhelmingly youthful. Between their late teens and 30s — too young to remember the glory years of the Habs.

Their presence speaks to the enduring mystique of the Canadiens. The team has left an indelible mark on the game and its fans because of its great players, its 24 Stanley Cup championships and the stirring victories it took to win them. The Canadiens are not the invincible force they once were — having won only two Cups in the past 30 years — and their rivalry with the Leafs has changed as well.

None of this matters to the fans on both sides of the divide who attend these games. They’re happy when their side wins. And when they lose, well, I suspect that they brush it off a lot quicker and easier than the kids of my generation.

A version of this article was first published in the April 2009 issue of Zoomer with the headline “100 Years,” p. 94.

RELATED:

Walter Gretzky: Reflecting on the Remarkable Life and Legacy of Canada’s Beloved Hockey Dad