Never Forgotten: Why One Canadian Writer Is Illuminating the Lives of Fallen Second World War Soldiers From His Community

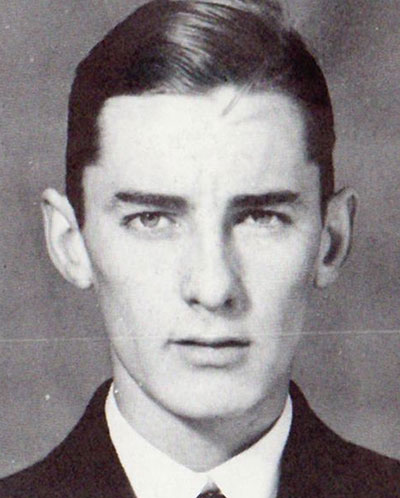

Malcolm (Mac) McIver, a former student at East York Collegiate Institute in Toronto. McIver died in the Second World War and, decades later, the sight of his name on the high school's memorial plaque inspired one journalist to undertake a major project to learn more about the lives of all the students from his former high school who died in the war. Photo: Courtesy of Veterans Affairs Canada

I have found myself over the many moons thinking about a name on the Second World War memorial plaque at my former high school, East York Collegiate, in Toronto’s east end.

It is that of Malcolm (Mac) McIver. He’s been dead for almost 80 years, killed when the training aircraft he was flying aboard in England “fell out of the clouds” in 1944.

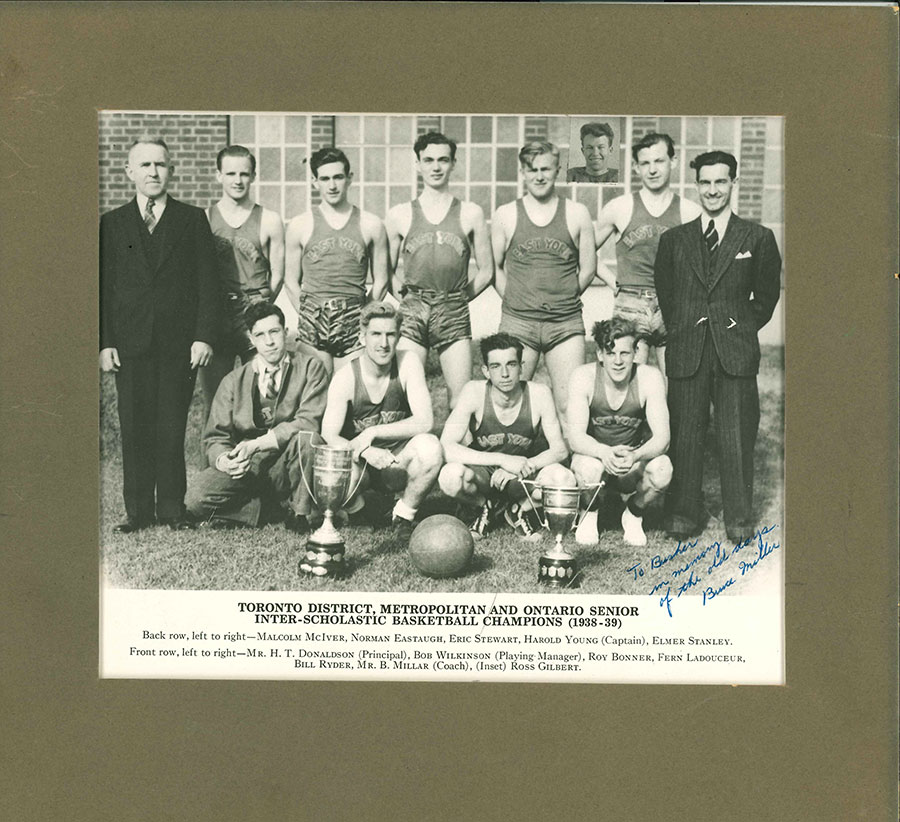

I knew the name at 13 when, as a first-year high schooler in 1973, I spotted it under an old sports photo (the 1939 Toronto District champion basketball team). What drew me was the “Malcolm.” There aren’t many of us out there, and this was neat for a kid.

I saw it again when the school’s 50th anniversary yearbook came out four years later, including the photo of a beautifully embossed certificate given to coach Bruce Miller in 1959 by the surviving members of that club. Two of the names, Elmer Stanley and Malcolm’s, had asterisks to mark their passing in the war.

And then, again, in 2002, at the school’s 75th anniversary celebration, when I was counting the 125 names on the brass plaque hanging in the foyer of the new school building built in 1988, after school board members had the original, beautiful art-deco structure torn down.

We find ourselves, yearly, trooping out to Remembrance Day ceremonies around cenotaphs, or in schools, or at former military bases, where we honour the names listed there. This is important, as it gives us a general sense of the sacrifice made by the approximately 45,000 Canadians (a stunning 10,000 in Bomber Command) who did not survive the Second World War.

But who were they? Who was Malcolm McIver? Who were the young men from my school, or my neighbourhood, who died and became names on a wall?

These questions prompted me to embark on two projects — one complete, the other well underway.

My novel SPROG: A Novel of Bomber Command, released in June 2021, tells of the youngsters (ie. “sprogs”), mostly still teens, training in the Royal Canadian Air Force — their music, films, pop culture, how they spoke to each other, and how they handled the danger they were about to face.

The other project began when the first was complete — researching and writing vignettes on the young men from my old high school, “The Collegiate,” who gave their lives in the Second World War. It adds stories and context to those names we mostly read on Remembrance Day, cut in stone, or on a plaque in bronze relief.

There are now more than 25 of them on the SPROG Facebook page. By the 100th anniversary of the school, in 2027, all will be done.

Here, a sampling of some of those stories:

Malcolm (Mac) McIver

Mac McIver was the middle son of Murdoch and Mary Glen (a family that also included four sisters), who all lived at 151 Mortimer Ave. By all accounts he was something special — an outstanding student and athlete and a quiet, nice guy. He was, in the pop culture parlance of the late 1930s, a Big Man on Campus down at the Collegiate.

MacIver joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1941 and became one of the more than 130,000 airmen who graduated across the country from the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. He was a natural navigator, with good math skills, calmness under fire and great leadership.

After a first tour of 30 operations with the famous No. 106 Squadron, Royal Air Force, McIver’s skills were recognized with a Distinguished Flying Cross for “outstanding ability, and the greatest keenness and enthusiasm for his work.”

Beating the odds on your first tour earned six months “off” instructing sprogs preparing for their own trips to hell and back. McIver’s assignment was No. 1655 Mosquito Training Unit, Warboys, England, preparing young navigators to fly on the hottest fighter-bomber of the war.

It was May 13, 1944, when McIver went up with a pilot and a couple of students in an Airspeed Oxford training aircraft for a routine navigational flight. Witnesses said the machine simply came down, reason unknown, and everyone was killed.

McIver is buried in Surrey, England.

When the war ended, however, there was not one but two beds empty at the McIver house.

After Malcolm left for war, younger brother Jack joined up to fly. He was training as a gunner when word of his older brother’s death reached him.

Jack would go down himself, in March 1945, while riding in the tail turret of an RCAF Liberator bomber in the Bay of Bengal. He has no known grave.

Only eldest son Glenn McIver came home from his service in northwestern Europe, with the Queen’s Own Rifles.

Elmer Stanley

McIver’s basketball teammate, Elmer Stanley, left his home on Gowan Avenue and joined the RCAF.

Identified as pilot material, he eventually made his way to final instruction flying twin-engine Avro Ansons out of Moncton, New Brunswick.

On 7 August, 1941, Elmer was coming in for a landing in Anson 6375 when something went wrong. He collided with Anson 6379, piloted by Francis Geldard, a graduate of Western Technical School, Toronto. Stanley, 20, was killed instantly. Francis, 22, died the next day in hospital.

Stanley is buried in the same plot as his parents, at Pine Hills Cemetery, in Scarborough.

George Gregg

George Gregg, of Cedarvale Avenue, married Marjorie Wannamaker in 1941 and welcomed little George Jr. into the troubled world a year later. Gregg was killed by a mortar fragment while fighting in France, shortly after D-Day in 1944.

Jimmie Skyvington

Sick Berth Attendant Jimmie Skyvington, from a big family on Wiley Avenue, tried to join the militia at age 15 and was turned away. When of age, he signed on with the Royal Canadian Navy and went down on the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan, in April of 1944. He and so many shipmates lay at the bottom of the Atlantic, off the northwest coast of Brittany, France.

Robert Haig Guthrie

Bob Guthrie, of Queensdale Avenue, flew his Harvard trainer into a barn on a foggy night in November of 1941, just short of the runway at St. Hubert, Quebec, leaving his wife Ethel pregnant with what would turn out to be twin girls. He had been an excellent skier and overall athlete.

And there are so many other stories to tell.

May those who were lost all be remembered for who they were and the lives they lived.

Visiting the McIver House Today

When you visit 151 Mortimer Avenue and press the doorbell, there is a two-note announcement.

Ding-Dong.

The same sound would have been heard in 1944 and 1945, when the McIver family was visited twice by Canadian Pacific Telegraph boys, bringing news that their sons Malcolm, and then Jack, had given their lives in the Second World War.

And now, it’s one of the historical features of the 1929 semi-detached house the new owners — Lorne Quitt and Annie Gamliel — were determined to preserve when they moved in around 18 months ago.

“That was really led by Lorne (her husband, a landscape designer),” says Annie Gamliel, a teacher. “Lorne loves ephemera, and antiques, and old maps … he loves items that have stories.

“So, when we bought the house he loved the original trim, he loved the doorbell … that was what excited him.”

As they explored and worked on their new home, I paid them a visit and told them of 151 Mortimer’s background. It had originally held the McIver family (including seven children), whose patriarch was himself a teacher and principal. During the war, they sent all three sons (Glenn, Malcolm, and Jack) off to fight.

Only the eldest survived.

The story hit home for Gamliel and Quitt.

“We were so excited to have this connection because sometimes, you have an antique and there is so much unknown,” says Gamliel. “When we heard the story, it made us feel like a part of history.”

That sense has always been a part of Gamliel herself, as her grandfather, Philip Epstein, is a Holocaust survivor.

A visitor to the home, meanwhile, is easily taken in by the experience. There is the original electric fireplace in the living room the McIver’s sat around on cold nights (not working, but preserved); the steep stairs that the boys would have raced up and down (something the dog, Eddie, now does with great aplomb); the dining room where nine people would eat most nights.

And then there’s the doorbell — a Rittenhouse Twin Tone Model 200 from 1937 that had been disconnected for years, which Quitt lovingly repaired.

Gamliel says the bell is big, and on a wall she had wanted, at first, to remove. But the bell wasn’t going anywhere. Especially when Quitt twigged to the idea that its sound was heard by the McIver family on those two occasions when bad news arrived.

It all makes them feel connected to this family, one that gave of itself to help liberate Europe and free the survivors of her Polish family.

“The house has a vibe, and it felt good,” she says. “This is a good house. A good home.”

One whose tale Annie and Lorne will honour, and pass along.

How to Honour the Fallen in Your Community

If you would like to begin researching your own community or school’s young men who gave their lives in the war, here are some tips:

First start is always the Canadian Virtual War Memorial, which contains basic information for each name. Some are more complete than others, thanks to efforts of families and friends over the years who have added their own photos and information.

If you are a family member, you can request military records from Library and Archives Canada here.

Some of these records are now fully open.

Royal Canadian Air Force records are the easiest to follow in large part because of the information that can be found on their website.

Army records can often be traced with the help of individual regiments, or associations tied to those.

Many of the ships that sailed with the Royal Canadian Navy have associations or websites dedicated to ships and their crews.

Finally, many of Canada’s military records are available at Ancestry.ca, for a small fee.

Malcolm Kelly is a Toronto-based journalist, professor and author of four non-fiction books. He released his first novel, Sprog: A Novel of Bomber Command, in 2021. Click here for more information.

* This story was originally published in 2022.

RELATED:

The Dieppe Raid: French Town Marks the 80th Anniversary and Honours 100-Year-Old Canadian Veteran

Legendary Canadian Veteran Richard Rohmer, 98, On His Unique Bond With Queen Elizabeth II