Meet Mick Herron, the Award-Winning Spy Novelist Some Call the Next John le Carré

Photo courtesy Mick Herron/Facebook

When U.K. MI5 intelligence agents excel, they might hope to end up at MI6. Others — whether due to errors of judgment, crossing the wrong superior or gross ineptitude — end their careers in ignominious defeat at Slough House. As far away from the expense accounts and nifty gadgets of James Bond’s “Q branch” as is possible, Slough House is the sublime creation of British novelist Mick Herron, 55, in his Jackson Lamb thrillers. And they’re the espionage series you should be reading right now.

Like a Lamb to the Slough House

This limbo of banishment is not actually in Slough, nor is it even a house. It is the British Intelligence Service’s “administrative oubliette” where it consigns its failures. Here, beyond the dusty black door sandwiched between a newsagent and a Chinese takeaway joint, below nicotine-stained ceilings, “as every office worker knows,” Herron writes, “it’s not the hope that kills you. It’s knowing it’s the hope that kills you that kills you.”

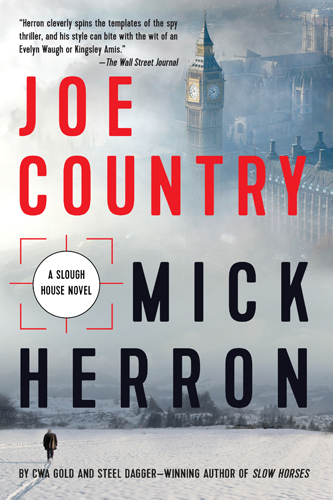

In 2010, Mick Herron’s Slow Horses introduced the regular cast of misfit and screw-up spies of what has now become an award-winning series (the sixth novel, Joe Country, is available as of June 21). The head of the so-called ‘slow horses’ is Jackson Lamb, though he doesn’t so much preside over the building as haunt it with affectionate loathing. Slovenly, obese, and profane, Lamb is a man of deliberate provocation and offensive put-downs and an anti-hero for the ages. When he’s on the scene the pages are populated with the sound effects of grunts, farts, and belches—from him or the building, which is a character in itself.

I’ve likened Lamb to Roald Dahl’s Mr. Twit crossed with Robbie Coltrane’s profiler Fitz, by way of fixer Malcolm Tucker. That last comparative makes even more sense now that Slow Horses has been optioned (by a producer whose credits include another compelling workplace, Homicide: Life on the Street) and is being adapted for BBC Television by Will Smith, co-writer of The Thick of It and Veep.

“The John le Carré of His Generation”

Crime writer Val McDermid declared Mick Herron to be, “the John le Carré of his generation.” She’s not wrong, if you consider his creation a sardonic inversion of le Carré’s famed intelligence officer George Smiley and “The Circus” (a.k.a. MI6) and that what he’s chronicling is a different sort of end of empire.

Herron’s examination of nationalist tendencies felt prescient upon publication of his first novel, Slow Horses, in 2010. Now, it seems like the series speaks directly to the current political situation in Britain. “Where Herron’s novels most overlap with those of le Carré is in the severity of their critique of the failures of management in post-imperial, pre-Brexit Britain,” the Guardian has said.

A female political leader who’s never named, for example, is described as not “so much made leader as handed a janitor’s uniform.” A Boris Johnson-like home secretary character with prime ministerial ambitions has, “retained the schoolboy looks and fluffy-haired manner that had endeared him to the British public and made him a staple on the less-challenging end of the TV spectrum: interviews conducted on sofas, by scripted comedians.”

Faced with these modern enemies, Lamb’s methods are often old-fashioned, even resolutely Luddite. “You can break a man’s ribs with a telephone directory,” Lamb offhandedly tells an underling; “Try doing that with a rolled-up copy of the internet.’”

He Who Laughs Last…

Mick Herron has also won the International Crime Fiction Convention’s Last Laugh Award — twice — for best humorous crime novel. His complex plots are riveting but the comic power of his dialogue make them the rare thriller that has you holding your breath even as you chortle with laughter. Wry one-liners somersault across the page with Wodehousian glee: “There was a dirty glass among the rubbish on his desk, and Lamb poured whisky into it; what might have been a triple, if your idea of a single was a double.”

At first, it’s actually hard to resist the urge to stop every few pages and for posterity jot down the memorable turns of phrase. (Of a borrowed getaway ride: “The thing about someone else’s car was, it was automatically an all-terrain vehicle.”) Soon, though, the marked passages become too many — or as the Evening Standard put it, “Herron has read his Carl Hiaasen as well as his Charles Dickens.”

Herron is a supreme prose writer of lyrical passages — especially on what endures, with musings on the rhythm of the metropolis and the rueful passage of time. Every building in every city, for example, “retains the echo of all it’s seen and heard…that is what memory is: an abiding awareness that some things have vanished.”

I, Spy?

The character Lamb, meanwhile, treats the flaws of his failed charges as assets. Some resign themselves to their fate, while others lament their reversal of fortune and file futile reports or pursue random leads in the hope of worming their way into good graces and invited back to headquarters again. And that’s where things get interesting, because the nature of their work comes with higher stakes than a jammed photocopier. Something innocuous invariably turns into intrigue and they variously end up doing fieldwork, or thwarting terrorist threats and assassins. (All this, by the way, before Luke Jennings had created Eve Polastri, the bored British Intelligence desk jockey of Killing Eve).

That’s another engrossing aspect of the novels that rings familiar: it rings true with annoying colleagues and the stultifying clock-watching boredom of a drab office comedy, but transposed into dealing with Islamists, assassination plots, post-Soviet Russia, and crucially, the war at home.

In writing, William Faulkner said by way of advice, “you must kill your darlings.” And Herron does, reconfiguring the players in his ensemble black comedy from book to book, with old and new screw-up spooks added or subtracted from the mix. The constant is Lamb, who for all his lumbering, the boss possesses surprising agility.

There’s a solid tradition of former detectives and spies like Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, Dashiell Hammett, Frederick Forsyth, and David Cornwell turning their experience into espionage fiction. After a thirty-year career with Britain’s Security Service that culminated in the role of director general, for example, Dame Stella Rimington in her retirement now writes a series about an MI5 intelligence officer. Mick Herron, however, is among the few top crime writers who hasn’t himself worked as an operative.

Or so he claims.

RELATED:

Louise Penny: Woman of Mystery

Vagina Monologues Author Eve Ensler Talks Feminism and Her New Book, The Apology