Philanthropy: Weathering the Charitable Recession

After a bruising year marked by declining donations and an embarrassing scandal, charity groups are hoping Canadians return to their generous ways. Photo: MicroStockHub/ GettyImages

With COVID-19 causing such massive health, social and economic convulsions, the demand for charity is at an all-time high. But in one of this pandemic’s many bitter paradoxes, a steep drop in donations means many organizations can’t fulfill their missions.

Amid so much economic anxiety, it’s no surprise many Canadians are tightening their belts and cutting down on discretionary spending.

“You can’t give to charity when you’ve lost your job and your financial security is up in the air,” concedes Kate Bahen, managing director of Charity Intelligence, a Toronto-based group that analyzes how charities use our donations.

Meanwhile, lockdowns, physical distancing measures and stay-at-home orders have cancelled lucrative fundraising events like walks, galas and door-to-door campaigns and, although charities supporting arts, culture, recreation and sport were hit the hardest, the Cancer Society and Heart and Stroke Foundation have also had to scale back on staff and services as the number of people requiring food banks, mental health assistance and domestic abuse shelters is way up.

“It’s a bad math equation for charitable organizations,” says Bruce MacDonald, CEO of Imagine Canada, a national group that lobbies the federal government on behalf of charities. “They’re simply not keeping pace.”

From big corporation-backed national health organizations to small local volunteer-run outfits, all rely on a business model that’s largely based on our ability — and willingness — to give. In normal years, we are happy to oblige — to the tune of $17 billion.

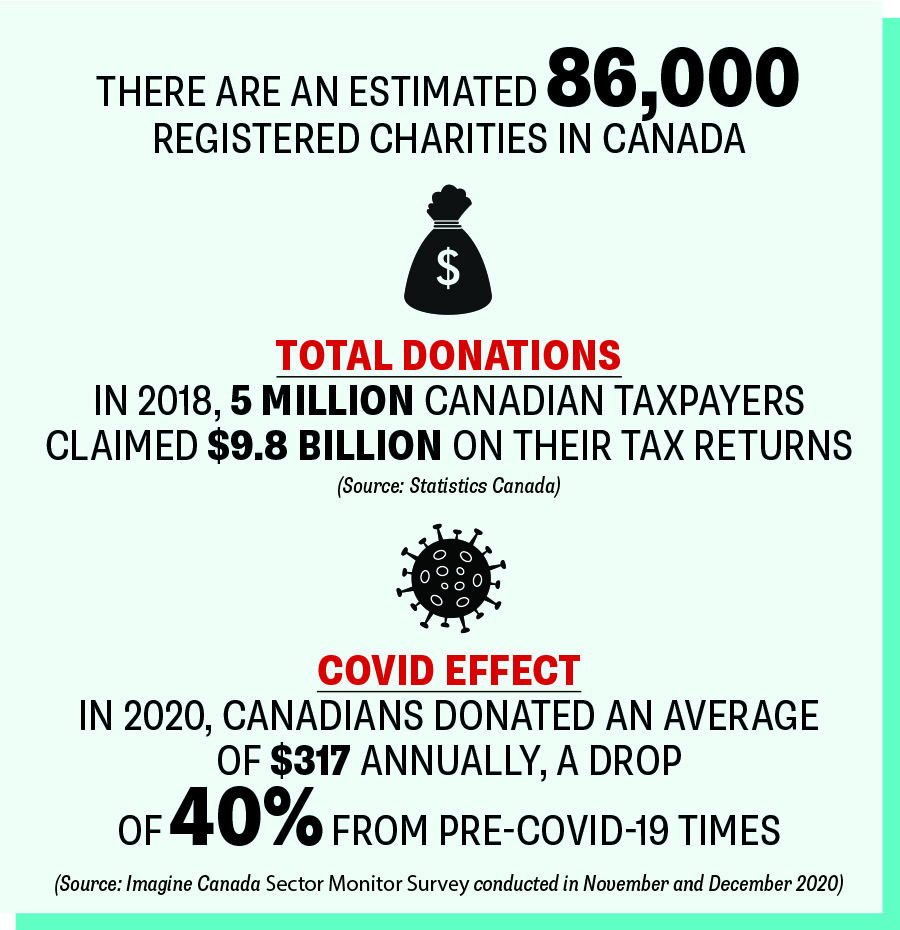

According to most recent Canada Revenue Agency figures, in 2018 five million of us claimed a charity tax credit, contributing nearly $10 billion in donations to 86,000 registered charities. On top of that, we give another $7 billion in cash donations to various fundraisers (such as the Salvation Army “kettle” campaigns, bidding on silent auctions, subscribing to seats at the orchestra or renewing our “Y” memberships) that we don’t claim on taxes.

MacDonald couldn’t put a figure on the financial impact of the pandemic on charities, but in April 2020, Imagine Canada estimated donations could decline by $4.2 to $6.3 billion. Last summer, it polled 1,089 of its 30,000 member organizations across the country, and MacDonald says 68 per cent of charities reported a decline in donations since the start of the pandemic.

The plunge in philanthropic support was also captured in an Imagine Canada online poll conducted on Dec. 5, 2020. Heading into the holiday season, when many people traditionally write big cheques to their favourite causes, almost half of 1,252 respondents were still planning to give to charity during the holiday season (down 11 per cent from previous years), but 36 per cent said they were planning to give less because of “financial difficulties related to COVID.”

The sector suffered another blow in June when the WE Charity scandal began dominating headlines. The international children’s charity, founded in 1995 by brothers Marc and Craig Kielburger, had just been awarded a $19.5 million contract to recruit student volunteers to take part in the government’s Canada Student Grant program. But after the Opposition got hold of media reports about Liberal connections to the charity — including speaking fees paid to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s family and two trips former Finance Minister Bill Morneau took on WE’s dime (but paid back, though he still resigned) — the government cancelled the contract.

A federal finance committee probe into the affair was cut short after Trudeau prorogued Parliament in mid-August, but a new inquiry continues to turn up more damning allegations against WE. With a labrythine structure that even one of its own board members didn’t understand and an eye-popping $40 million dollars worth of real estate, WE is accused of shuffling money between its for profit and not-for-profit companies. Further, that it employed questionable record-keeping and fundraising tactics, including using multiple donors to fund the same program.

The fiasco not only spelled the end of WE Charity’s Canadian operations but also bruised the reputation of the entire charitable sector. “It sent a tremor to the foundation of trust of the whole charity sector,” says MacDonald. “Many people began to ask: ‘How’s my favourite cause stacking up?’”

Bahen says all the negativity surrounding charities may have been a blessing in disguise because it has forced us to become better-informed givers. Before supporting a cause, we’re now researching organizations to ensure they use our money wisely and they make a real social impact. To help, Charity Intelligence’s website (charityintelligence.ca) offers its annual Top 100 Rated Charities report, which analyzes organizations using a host of metrics, including “transparency, results reporting, need for funding, cents to the cause, and demonstrated impact.”

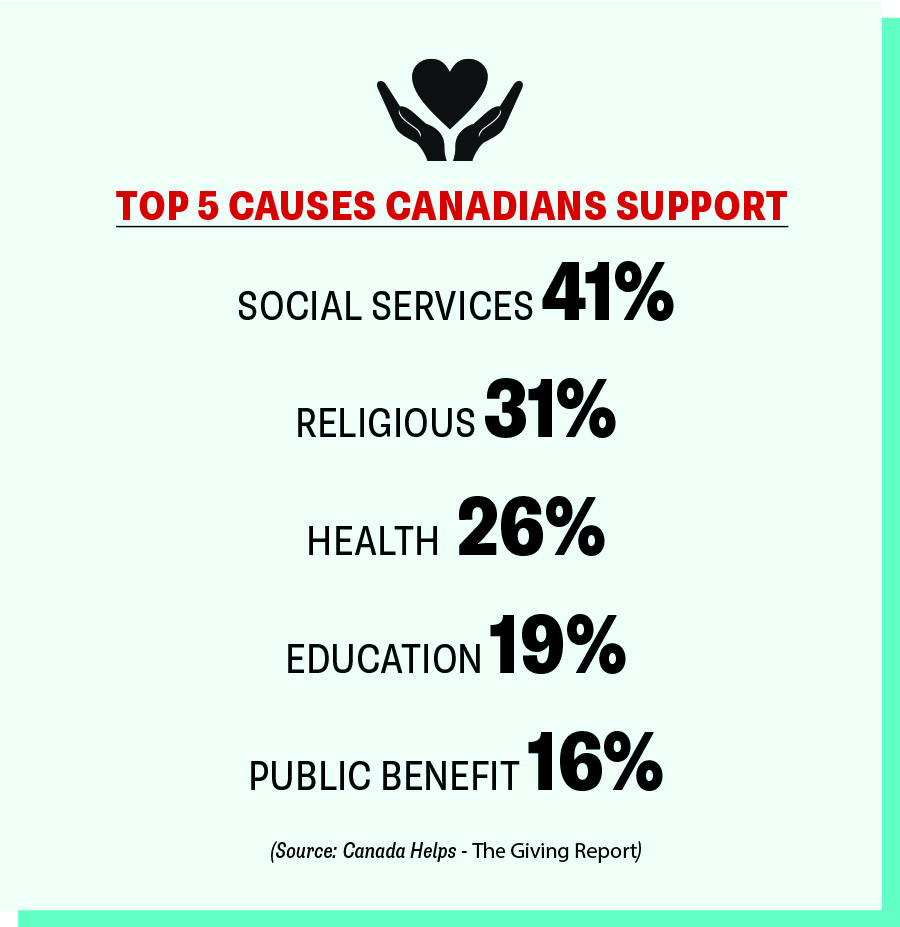

“We’re trying to inform Canadians where their charitable dollars can do the best work possible,” says Bahen, who has noticed an uptick in website traffic and a “pivot” in our giving habits. “Before, Canadians would often give to big charities, brands they could trust,” she says. “Now they’re looking to support community groups that dedicate their resources to essential frontline services — like food banks, shelters or crisis lines.”

To help charities survive, Imagine Canada is urging Ottawa to bail out the sector and provide either stabilization funding or by offering to match public donations, similar to what governments do during fires or natural disasters.

MacDonald also suggests that Canadians who have weathered the financial crisis relatively unscathed might kickstart a philanthropy blitz similar to the spending frenzy some economists are predicting will unfold once the pandemic is behind us.

“Our sector is hoping that as the pandemic fades and the economy reopens, donor generosity will surge,” says MacDonald. “Our hope is that the return to ‘normal’ will spark confidence among Canadians who haven’t been financially affected by the crisis, or who have perhaps not donated as much during the pandemic. A surge in donations could make a significant difference for organizations and the communities they serve.”

Ultimately, MacDonald feels Canadians have a social responsibility to care for the less fortunate. “These organizations provide necessary services in our communities,” he says. “Society has a role to play in making sure they’re available.”

A version of this article was first published in the April/May 2021 issue with the headline “A Charitable Recession,” p. 52.

RELATED:

Family of Alex Trebek Donates His ‘Jeopardy!’ Wardrobe to Charity That Helps Men Escape Poverty